A DEATH IN THE UNION

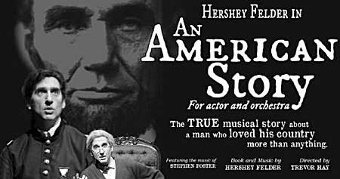

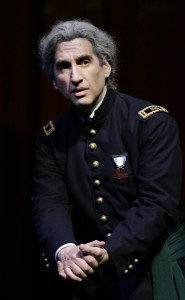

Hershey Felder has already regaled audiences at the Royal George Theatre with his uncanny and heartfelt recreations of George Gershwin, George M. Cohan, Frederic Chopin, Leonard Bernstein and Ludwig van Beethoven, honoring and invigorating the music as much as he concentrated their life stories. Now he delivers a solo tour de force, An American Story for Actor and Orchestra, enjoying a Chicago premiere after tryouts in Los Angeles and San Diego. The show has been tinkered with since Stage and Cinema reviewed the LA production, which was originally directed by Joel Zwick and titled Lincoln: An American Story. Now, director Trevor Hay has come on board and the result is a highly rewarding entertainment.

With auxiliary artfulness, Felder turns to Abraham Lincoln to tell the sad story of the Civil War’s last casualty, occasionally sweetened by the ever-nostalgic songs of Stephen Foster, whose “My Old Kentucky Home” could easily refer to Lincoln’s childhood. We’re in New York City circa 1932’”but we’re looking back 67 years to a convulsive night in Ford’s Theatre in Washington City, a not so Good Friday’”April 14, 1865. Felder plays Dr. Charles Augustus Leale, now 90, as he recalls his experience as a 23-year-old apprentice surgeon for the Union Army with a rendezvous with destiny. It’s Leale who, according to his own account of Lincoln’s Last Hours, was the first person to enter (actually, break into) the Presidential box after John Wilkes Booth sealed his doom. Mrs. Lincoln insisted that Leale remain with the President to the last when Lincoln’s heart gave out after 7 a.m. (Leale’s original report appeared in 1865 but was lost until miraculously discovered last year, hidden amongst Lincoln’s papers in Washington.)

With auxiliary artfulness, Felder turns to Abraham Lincoln to tell the sad story of the Civil War’s last casualty, occasionally sweetened by the ever-nostalgic songs of Stephen Foster, whose “My Old Kentucky Home” could easily refer to Lincoln’s childhood. We’re in New York City circa 1932’”but we’re looking back 67 years to a convulsive night in Ford’s Theatre in Washington City, a not so Good Friday’”April 14, 1865. Felder plays Dr. Charles Augustus Leale, now 90, as he recalls his experience as a 23-year-old apprentice surgeon for the Union Army with a rendezvous with destiny. It’s Leale who, according to his own account of Lincoln’s Last Hours, was the first person to enter (actually, break into) the Presidential box after John Wilkes Booth sealed his doom. Mrs. Lincoln insisted that Leale remain with the President to the last when Lincoln’s heart gave out after 7 a.m. (Leale’s original report appeared in 1865 but was lost until miraculously discovered last year, hidden amongst Lincoln’s papers in Washington.)

Felder’s witness backs up a bit too far to describe his own life before Lincoln’s death, but he generously evokes an era with telling details. We hear how, after taking the eight-year-old “Charlie” to the Christie Minstrels featuring a racist, gesticulating “Jim Crow” in blackface (and Felder raucously sings the original jubilee), Leale’s father warned him never to deny respect to others or to himself. We learn how he began establishing children’s hospitals in New York City, how he would eventually care for the dying Stephen Foster, and how he saw the astonishingly good-looking John Wilkes Booth play Julius Caesar (it should have been Brutus) in 1864 on a night when “copperhead” traitors tried to burn down New York City. (He also saw Booth, as a photograph also reveals, staring at Lincoln as he gave his Second Inaugural Address.)

Felder’s witness backs up a bit too far to describe his own life before Lincoln’s death, but he generously evokes an era with telling details. We hear how, after taking the eight-year-old “Charlie” to the Christie Minstrels featuring a racist, gesticulating “Jim Crow” in blackface (and Felder raucously sings the original jubilee), Leale’s father warned him never to deny respect to others or to himself. We learn how he began establishing children’s hospitals in New York City, how he would eventually care for the dying Stephen Foster, and how he saw the astonishingly good-looking John Wilkes Booth play Julius Caesar (it should have been Brutus) in 1864 on a night when “copperhead” traitors tried to burn down New York City. (He also saw Booth, as a photograph also reveals, staring at Lincoln as he gave his Second Inaugural Address.)

Leale shares a soldier’s anecdotes of Union and Confederate soldiers facing each other across the breastworks and exchanging not bullets, but songs’”competing until finally they find a brief common cause in “Home, Sweet Home.” Walt Whitman tends wounded soldiers, and draft rioters destroy Gotham. Blending the better with the bitter, we also hear gorgeous ballads and poems by Foster as well as John Howard Payne and Henry Bishop.

But, of course, Leale’s core confession is his guilt-ridden account of how he was unable to do more than stanch the bleeding from the bullet in the back of Lincoln’s skull’”a bullet which had probably rendered Lincoln brain-dead from the instant it was discharged. It’s all here: Actress Laura Keane holding the President and singing “Beautiful Dreamer” over the crumpled leader; the hasty transport of the body across the street to the Peterson boarding house where Lincoln’s lanky body was lain cross-wise on the bed; Mrs. Lincoln’s increasing hysteria in an otherwise quiet death chamber; the long night’s vigil as Leale tries to relieve his breathing; Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s frenzied questioning of witnesses in the next room; the final last breath as the sun rose; and the funeral procession where Leale was in the lead. (The only thing left out was Stanton’s famous’”and disputed’”valedictory after the 16th President dies: “Now he belongs to the ages.” Or was it “angels”?)

But, of course, Leale’s core confession is his guilt-ridden account of how he was unable to do more than stanch the bleeding from the bullet in the back of Lincoln’s skull’”a bullet which had probably rendered Lincoln brain-dead from the instant it was discharged. It’s all here: Actress Laura Keane holding the President and singing “Beautiful Dreamer” over the crumpled leader; the hasty transport of the body across the street to the Peterson boarding house where Lincoln’s lanky body was lain cross-wise on the bed; Mrs. Lincoln’s increasing hysteria in an otherwise quiet death chamber; the long night’s vigil as Leale tries to relieve his breathing; Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s frenzied questioning of witnesses in the next room; the final last breath as the sun rose; and the funeral procession where Leale was in the lead. (The only thing left out was Stanton’s famous’”and disputed’”valedictory after the 16th President dies: “Now he belongs to the ages.” Or was it “angels”?)

Apart from the power of the testimony and Felder’s concentrated portrayal of a true patriot, An American Story is also beautiful to behold, with the Royal George, surprisingly similar to Ford’s Theatre, decorated by David Buess and Trevor Hay in patriotic bunting with evocative projections displayed on the many curtains that drape the stage. The President’s box is accurately displayed along with the Lincoln’s scarlet rocking chair. The accuracy applies even to the show’s program, a perfect evocation of Victorian artwork.

Apart from the power of the testimony and Felder’s concentrated portrayal of a true patriot, An American Story is also beautiful to behold, with the Royal George, surprisingly similar to Ford’s Theatre, decorated by David Buess and Trevor Hay in patriotic bunting with evocative projections displayed on the many curtains that drape the stage. The President’s box is accurately displayed along with the Lincoln’s scarlet rocking chair. The accuracy applies even to the show’s program, a perfect evocation of Victorian artwork.

The one-act reclamation is just as wonderful to hear, with a ten-person orchestra delivering Hershey’s supple musical backdrop as well as charming period numbers like “The Bonnie Blue Flag” and its Northern equivalent. There’s another type of music as well’”the superb cadences and gorgeous diction of Lincoln’s speeches, here represented by the Gettysburg and the Second Inaugural Addresses.

An American Story is, in fact, a perfect 85-minute package, a time trip that earns its sentiment as it reclaims a 148-year-old tragedy from which we have yet to recover.

photos courtesy of Eighty Eight LLC

An American Story for Actor and Orchestra

Eighty-Eight Entertainment at Royal George Theatre

scheduled to end on April 14, 2013

for tickets, call 312-988-9000 or visit http://www.theroyalgeorgetheatre.com

for info on this and other Chicago Theater, visit http://www.TheatreinChicago.com