THE MISCHEVIOUS INDEMNITY OF NOIR

You can bring a blanc sensibility to noir, but noir finds a way of seeping in’”its luxurious, sweet poison stealing focus when you’re not looking.

In Billy & Ray, playwright Mike Bencivenga and director Garry Marshall set out to tell the undeniably funny story of how Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler created the classic Double Indemnity over the course of fourteen months, while becoming frenemies on the Paramount lot in 1942 and 1943. They are as odd a couple as Neil Simon could invent: Wilder, the devilish, Austrian sybarite is the polar opposite of Chandler, the dour, Midwestern, Grant Wood sourpuss.

Wilder and his longtime partner Charles Brackett are on what, as any film fan knows, is to be a temporary break, and Wilder and Chandler execute a one-time-only collaboration that results in cinematic magic.

Chandler has to be lured into the seductive embrace of Movieland, and it’s a bit like watching a horror film, where the hapless hero’s car breaks down and he decides to go to the haunted house on the hill to ask for help’”even though it’s on fire and dead things are flying out of its chimney. You scream at the screen: “Don’t do it!” But the idiot never listens. Sometimes he lives, sometimes he dies, but he always suffers.

The suffering is the fun.

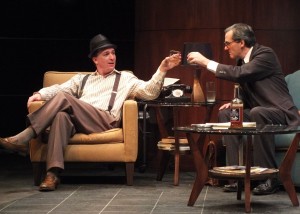

And so it is here. Barbs are fast and furious, Goldwynisms show up happily on schedule, and the jokes mostly hit their marks’”but the real show unfolds as Wilder embarks on a cheerfully sadistic mission to drive Chandler, a semi-dry alcoholic, to re-pickle himself.

That the drinking doesn’t end well is not a surprise, nor is it meant to be, but it is utterly fascinating. There’s a hurried attempt at the end to mitigate the cruelty with an epilogue citing Wilder’s subsequent film The Lost Weekend, a gritty, yet largely sympathetic, study of an alcoholic writer (that rather ironically goes on to win all the Oscars in 1945 that Double Indemnity will lose to the saccharine Going My Way in 1944) but the inference of Wilder’s remorse over returning Chandler into the depths of hell doesn’t resonate as strongly as the gleeful pride he takes in giving Chandler the push.

There is satisfying humor in Wilder’s charming machinations to get the lurid story’”adapted from the even more lurid James M. Cain novel’”past the censors, and in the way he convinces the recalcitrant (and off-stage) Barbara Stanwyck and Fred McMurray to risk their reputations to join in the fun, as well as in his affable torment of both gal Friday Helen and studio exec Joe Sistrom.

One caveat: The joke about MacMurray doing Double Indemnity so he can do Stanwyck is funny. The one that references My Three Sons is cheap, and takes you right out of the story.

So the funny is there, but the dark’¦ it is as enticing as Hollywood itself.

Blanc paying its debt to noir in a play about the making of a film noir masterpiece is as it should be. It was a movement that married the grand stylishness of American filmmaking to postwar despair and self-aware cynicism. Though the largely forgotten Stranger on the Third Floor starring Peter Lorre in 1940 is what many cineastes cite as the first American film noir (it is a hotly debated issue), Double Indemnity is reasonably in the running. It was a highly influential film, helping to  define noir’s style’”beautiful, inky sojourns into glorious, masochistic irony’”stunningly lit, improbable, and sublime. Noir is the cinema where just there, lurking in the shadows, the treacherously hot leading lady says, “Go ahead, shoot me,” and the manly, rumpled anti-hero downs a shot of whiskey and does just that. Then for good measure he offs himself, bidding good riddance to them both.

define noir’s style’”beautiful, inky sojourns into glorious, masochistic irony’”stunningly lit, improbable, and sublime. Noir is the cinema where just there, lurking in the shadows, the treacherously hot leading lady says, “Go ahead, shoot me,” and the manly, rumpled anti-hero downs a shot of whiskey and does just that. Then for good measure he offs himself, bidding good riddance to them both.

Billy & Ray hinges on the performance of the actor playing Billy Wilder, and Kevin Blake comes through. His elfin, manic energy is persuasive and well-calibrated, even if his Austrian accent gets a bit Swedish here and there. With Blake’s performance, you believe Wilder’s success at convincing everyone around him to do his bidding. I wish the script asked more of him though’”that it made him work harder to get his way. Playwright Bencivenga has a difficult task. Much of the audience knows how this all turns out, so there is little tension or suspense in the questions of whether Wilder prevails with the censors, whether he convinces Chandler to work with him, or whether he gets the cast he wants. So we have to be drawn into wondering how he will do it, rather than whether he will succeed.

Wilder getting his way is never in doubt.

There is a nice chemistry between Blake and his co-star Shaun O’Hagan, who is lanky and satisfyingly awkward in his approach to Raymond Chandler. O’Hagan has the timing and patience to play the straight man, but expertly seizes the moment when Chandler gets a couple of opportunities to one-up Wilder. Yet as he does with Wilder, Bencivenga makes things a tad too easy. Never mind that history tells us Chandler’s involvement is a done deal; as written, it never even feels like he truly wants to walk away, regardless of how often he says he hates the gig. Though in fairness, maybe that’s a problem of perception. Since we can’t really conceive of anyone not wanting to write with the legendary Billy Wilder, it follows that we can’t really take Chandler’s distaste for him seriously.

The script also relies heavily on Chandler’s reputation. If Wilder really wants Chandler to work with him on Double Indemnity so much, show us why, don’t just keep telling us how great Chandler is. There’s a whole sequence where Wilder talks about the difference between showing and telling in film. In this case, don’t tell us, let us hear it.

As Helen, Ali Spuck has gams for days and terrific timing, playing a sort of younger, sexier version of Thelma Ritter. The character is often lumbered with expositional phone calls that could be clunky, but Spuck makes them goofy and sweet. Anthony Starke hits all the right notes as the studio exec, but the role is more of a structural device than a full character. Starke appears to have the comic chops to give more than he gets.

One of the best things about the production is Keith Mitchell’s fantastic set’”a series of angles allowing for great fluidity. Best of all, you can easily imagine how wonderful it would look in black and white. Beaudry is obviously using film noir as source material, and he does it with great invention and humor.

The other triumph is the staging. Garry Marshall, working with assistant director Joseph Leo Bwarie, creates engaging movement, not just utilizing the space, but channeling the cast’s comic energy with easy confidence. You don’t have to know anything about Marshall’s status as a Living Legend (a moniker that is almost never welcomed by anyone) to recognize and appreciate the depth of experience and hard work it takes to make a show look this effortless.

There’s a great callback joke involving Chandler’s pedantic insistence that a great piece of business Wilder creates for Stanwyck is absolutely wrong, because it relies on an entrance door to an apartment incorrectly opening outward into the hall. To Wilder, if that’s what the audience is noticing by that point in the movie, then the script has bigger problems than a wrong-way door. Wilder wins. But at the end of the play, for the callback, there’s a nice nod to Chandler’s point of view.

In this case, with this material, I’m Chandler. I’m an avid student of the era, of Wilder, and of how the studio system worked in the 40s. I could launch into a nitpicky snit about tiny historical mistakes, but in doing so, I fear I would bore even myself. So I’ll do a deal with the producers. I won’t pick, if they promise to persuade costume designer Terri A. Lewis to replace Kevin Blake’s pants and shoes (which, for a trillion reasons, are wrong, wrong, wrong!) Can we shake on it?

photos by Chelsea Sutton

Billy & Ray

Falcon Theatre in Burbank

scheduled to end on April 28, 2013 EXTENDED to May 5, 2013

for tickets, call (818) 955-8101 or visit http://www.FalconTheatre.com

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I’m not sure how much of your opinion we can trust when you clearly didn’t even read the program. Selah Victor is the understudy. You saw Ali Spuck. Give credit where credit is due.

We have corrected the error.