A DARK, RIVETING AND WORTHY TRIP TO THE FOREST

An undeservedly small house took in Friday’s performance of Caryl Churchill’s brilliant, unsettling Mad Forest. Commissioned in 1990 in response to the events of the 1989 Romanian Revolution, this is a challenging piece of theatre that Open Fist deserves recognition for producing. Under Marya Mazor’s smart, layered direction, the large company of actors aggressively plumbs the sharp shifts of character and style required by Churchill’s versatile postmodern text, a text which engagingly weaves many stories, ideas, feelings and individuals together under the contextual banner of a major albeit perplexing historical event.

The play is divided into three parts, with the first focusing on life before the revolt. Romanians wait in long lines for food; a young woman uses bribery and double-talk to secure an illegal abortion; and most importantly, families and individuals sweat under the constant, stifling threat of an oppressive communist regime run by informants (little brother) and the Securitate (big brother). Mazor quickly and effectively stages Churchill’s vignettes with aptitude and vigor, crafting artful fragments that begin to lock into each other like pieces of a puzzle. The flexible yet specific set design (Richard Hoover) and the lighting design (Wyatt Bartel/PRG-LA) offer an efficient and visually intriguing use of space, quickly and skillfully creating the many locations ’” kitchens, bus stops, factories, street corners ’” where these charged moments occur (Liam Carl’s projections and Tim Labor’s sound round out the design team). In the occasional off moment, when the action onstage failed to carry us into the next beat, the tech elements succeeded in buoying the story: For instance, when actor Ryan Mulkay did not quite succeed in grounding himself as a questioning, ethically tormented priest, Bartel placed him in the broken yet beautiful colored light of a stained glass window, supporting the scene’s intentions.

The play is divided into three parts, with the first focusing on life before the revolt. Romanians wait in long lines for food; a young woman uses bribery and double-talk to secure an illegal abortion; and most importantly, families and individuals sweat under the constant, stifling threat of an oppressive communist regime run by informants (little brother) and the Securitate (big brother). Mazor quickly and effectively stages Churchill’s vignettes with aptitude and vigor, crafting artful fragments that begin to lock into each other like pieces of a puzzle. The flexible yet specific set design (Richard Hoover) and the lighting design (Wyatt Bartel/PRG-LA) offer an efficient and visually intriguing use of space, quickly and skillfully creating the many locations ’” kitchens, bus stops, factories, street corners ’” where these charged moments occur (Liam Carl’s projections and Tim Labor’s sound round out the design team). In the occasional off moment, when the action onstage failed to carry us into the next beat, the tech elements succeeded in buoying the story: For instance, when actor Ryan Mulkay did not quite succeed in grounding himself as a questioning, ethically tormented priest, Bartel placed him in the broken yet beautiful colored light of a stained glass window, supporting the scene’s intentions.

Part Two covers the uprising itself with the immediacy of first-person confessionals, crafted from interviews with Romanian participants in the immediate aftermath of the Revolution, Special credit should be given to Kiley Eberhardt, Allison Mattox and Chuck Filipov, largely responsible for carrying this section, and to Jennifer Schoch for her turn as a young mother psychologically disabled by life under CeauÈ™escu’s choiceless regime; the cast creates a rising sense of dread and  clautrophobia. Mazor’s production skirts sensationalism and never bombards us with bloody bodies; her choice to embrace the subtlety of the piece richly pays off.

clautrophobia. Mazor’s production skirts sensationalism and never bombards us with bloody bodies; her choice to embrace the subtlety of the piece richly pays off.

Part Three follows the unfolding lives of the family and friends we were introduced to in Part One as they celebrate and cope with the new lives they have made post-revolution. As artfully presented here, postmodernism seems the obvious filter through which to view the troubling events of 1989, whose meanings and even histories seem to shift with the passing of time and the changing of viewers. By structuring the play to match the disturbing event at its center, Churchill demonstrates great artistic sensitivity, and Mazor’s production succeeds in introducing the audience to this dangerous, dark world.

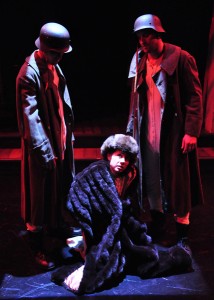

In the aftermath of the revolution, there is a scene titled “Radica is still having nightmares.” Radica (Pilar Alvarez) endures a bad dream in which she is taunted by soldiers who exchange identical uniforms, take her money while promising a helicopter, and proceed to laugh menacingly while cutting off her hands and feet. It is not until later in the play, when Radu (Rene Millan) and Irina (Jessica Noboa) drunkenly reenact the assassination of CeauÈ™escu and his wife Elena, you realize  that in Radica’s nightmares, she identifies with Elena, and that the roles of victim and oppressor have not been overcome, just reversed.

that in Radica’s nightmares, she identifies with Elena, and that the roles of victim and oppressor have not been overcome, just reversed.

The struggle of a people to overcome both the pain of oppression and the growing pains of sudden freedom is beautifully explored, and given the events of the past few years (think of the Arab Spring, or the ongoing crisis in Syria) the story is more timely and important than ever. Just as Sara Ryung Clement’s costumes transition from dark, plain pieces of a bygone era into the brighter, sexier styles of the actual time, so the characters’ body language and speech opens up once CeauÈ™escu has been executed. They dance and shout, and find themselves up against old problems with new faces. Just because CeauÈ™escu has been overthrown doesn’t mean Lucia can finally marry the Hungarian man she loves but her family hates. Radu turns against his own mother in reporting her pro-CeauÈ™escu teaching to the new extremist group gaining power. As an uncomfortably penetrating vampire (Jan Munroe) states, “You begin to want blood.”

The production is not without its flaws: trying to get eighteen actors to speak with the same Romanian dialect without using a dialect coach seems a bit pie in the sky; a couple of vignettes fall flat; and at times there are just too many things happening onstage at the same time. Still, these slight blemishes seem unimportant when taken in the context of the whole. The play and this production are, like the source material, a “mad forest” – sprawling, massive, wild. While the performers do not always find that theatrical Garden of Eden between spontaneity and precision, the experience at Open Fist is highly recommended.

photos by Ehrin Marlow

Mad Forest

Open Fist Theatre Company in Hollywood

scheduled to end on May 4, 2013

for tickets, visit http://www.openfist.org