THE DISHARMONY OF FORCED UNDERSTATEMENT

Set in a village in the hinterlands of Kazakhstan, Harmony Lessons centers around a young teenager named Aslan (Timur Aidarbekov), who washes obsessively and executes cockroaches in novel ways. A poor loner and outcast who lives with his grandmother, Aslan goes to a school dominated by a classmate named Bolat (the excellent Aslan Anarbayev), a bully and self-styled mini godfather who, with the help of his flunkies, extorts money from kids and beats them up if they do not pay. Aslan’s isolation is mitigated somewhat when a newcomer, Mirsayin (Mukhtar Andassov), arrives at the school from the big city, and becomes Aslan’s only friend.

Written, directed, and edited by Emir Baigazin, Harmony Lessons feels like one long false note, which is almost imperceptible at the beginning but grows louder as the movie progresses, eventually culminating in a grating finale that takes the form of a third and final dream sequence (which is just as pointless and uninteresting as the previous two). This isn’t to say that filmmaking skills aren’t in evidence in this well-intentioned Kazakh-French-German production. On the contrary, the sense one gets is that Harmony Lessons was made by a straight-A graduate of a film school in the former Soviet Union. Mr. Baigazin appears to understand what a director’s responsibilities are and seems to have a solid grasp of the fundamentals: he knows how to create mise-en-scène, how to choose which shots he wants, how to communicate with actors and elicit the kinds of performances that suit him, and how to create a consistent world based on a singular vision, which he also appears to possess. Unfortunately, that vision, in the case of Harmony Lessons, is uncompelling, the film dull and lifeless. Still, one does get the hopeful sense that perhaps this is the result of a novice filmmaker’s timidity – a fear, for lack of experience or confidence or resources, of getting tangled up in too many details and losing control – rather than, say, a lack of insight or creative abilities.

A fundamental problem with Harmony Lessons is that Aslan, the main character, is unsympathetic, not because of anything he does but because he doesn’t react to anything; we get no meaningful insight into him. In fact the most likable personage is Bolat, the villain; even though he’s a lowlife at least he’s doing something, as well as reacting to what is being done to him. One would think that lack of sympathy wouldn’t be much of an issue when making a film about children, who generally can’t help but be charismatic. But Mr. Baigazin manages to squeeze what natural life they have out of them in order so that he may stuff them into his boxy vision. In general the film appears to be directed as written (a common pitfall for novice writer/directors), with events stacked like wooden blocks one after another, as opposed to flowing organically from one into the next.

The film is understated in the extreme, and this works to a certain extent. But after a while the understatement begins to feel less like a stylistic choice to support the illusion that we are peeking in on real life and more like a way to disguise the filmmaker’s limitations; there is little sense of the personages and their world existing outside the frame and what one would think would be pivotal scenes of physical conflict and emotional turmoil are conspicuously avoided.

Another thing to jump out at the viewer is how deliberate everything about this film is, with every frame constructed just so, every movement precisely orchestrated; every one of the shots, which are mostly static and on the long side, seem to be screaming “PAY ATTENTION!” Unfortunately, while many of the images do make for lovely pictures (cinematographer: Aziz Zhambakiyev) most of them lack the directorial artistry to make them dramatic and therefore cinematically compelling. One gets the sense that not only is Mr. Baigazin trying to make an auteur film but that it’s even more important for him to let us know it. Such an assertion, when it isn’t backed up by what is up on the screen, can in itself be a little off-putting and tiresome.

There is a tendency for young filmmakers from what is now the former USSR who aspire to create high art to emulate the likes of Tarkovsky and Parajanov, especially when it comes to the masters’ long, often static shots, and the ultra-specific details that fill every one of their frames. The problem with this is that one essentially has to be a Tarkovsky or a Parajanov to get away with it. For Mr. Baigazin, who seems neither talentless not incapable, a better approach might be to begin by focusing on creating simple but compelling life on the screen, with dramatic arcs and fully-formed characters. If the result is high art, all the better. But if not, at least the final product will be (one hopes) an engaging, dramatic spectacle, instead of a stylized and carefully crafted but ultimately banal and very boring “artistic” statement that doesn’t ring true.

photos © Courtesy of Tribeca Film Festival

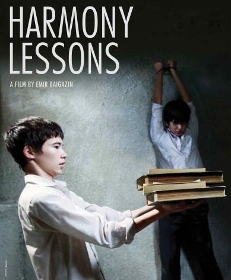

Harmony Lessons

JCS Kazakhfilm, Post Republic Halle, Rohfilm, and Arizona Productions

Kazakhstan / Germany / France – 2013 – Color – 110 min.

North American premiere at Tribeca Film Festival

for screening times, visit Tribeca Film