MAGNIFIQUE

Sometimes, dance performances are entertaining, but only for the spectator who understands the storyline behind the dancing. Other times, the performances are less about dance and more about the esoteric, self-righteous fulfillment of the dancer being able to perform. Where is the line drawn between these forms and how does the viewer know when a dance performance is good? With the collaborative work from Diavolo Dance Theater, the movement speaks for itself. There is no need to interpret what is going on. You are not forced to watch the virtuosity of the dancer. You simply watch what unfolds and are stunned.

This is what happened at the premiere of Diavolo’s Fluid Infinities, but before the dancers took the stage to deliver this main course, conductor Bramwell Tovey and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra performed two sumptuous aperitifs. The first was a rousing and riveting version of the continually climaxing and locomotive Chairman Dances by John Adams; a fitting prelude for the evening of sprawling, spiraling music. Tovey then waxed in his jocular and eloquent manner about his Act I and II selections from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, beat-by-beat, seated at a piano stage-right. His fifteen minute lecture detailing the intrinsic moods, modes, and motifs in Prokofiev’s celebrated ballet helped the audience better appreciate and lend a more tuneful ear to the already beautiful and striking music. The dichotomy of selections chosen veered from virile violence (“The Quarrel,” “Mercutio Fights Tybalt,” “Romeo Avenges Tybalt”) to the tenderly romantic (“Balcony Scene,” “Romeo’s Variation,” “Love Dance”). The stark contrast made for a vivacious and invigorating performance with Sarah Jackson’s lilting flute lines of particularly airy beauty.

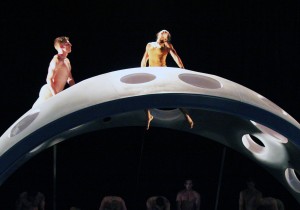

Fluid Infinities was spellbinding, unique, and exceptional. The exactitude of the synchronicity of the dancers’ movements with the Los Angeles Philharmonic was unquestionable. Tovey conducted a stripped down strings orchestra comprised of nineteen of LA Phil’s finest to perform Philip Glass’ concise (twenty-four minutes long) Symphony no. 3. Showcasing Tovey’s elastic dexterity between minimalism, twentieth century music, and post-modern music, LA Phil provided a propulsive and kaleidoscopic backdrop for Diavolo to exploit with their radical imagining of space and movement. Glass’s works are well-known for their repetitive schemes, and the third movement of Symphony no. 3 is remembered for its brilliant baroque-inspired chaconne. Hearing Glass’s most classically-based work in this space coupled with Diavolo’s choreographed movement, we are afforded a luxurious, novel dimension of hypnotic life. The music moves through the dancers much like the dancers swerve and dive through the pockets of the quarter-spherical shape on stage–with elastic grace and profound strength.

Moreover, the set design was complimentary to the actual stage set-up at the Hollywood Bowl: The dancers moved as though they were in a large picturesque frame since the sphere was mirrored by the large, round infrastructure. At one point the lighting team, led by designer John E. D. Bass, manually moved the stage light to enhance the performance as the dancers moved in and out of the shadows created by the sphere. Additionally, for the entirety of the performance four television screens projected the dance from the stage so those further back in the audience could also view the action of the dancers up close.

Having previously seen the works-in-progress in July, I found many of the thematic, choreographic changes highly successful. The audible laughs that were heard from the audience as Leandro Damasco was the first to be sucked into the sphere only confirmed the success of the changes. Moreover, a much deserved round of applause erupted at the close of Chisa Yamaguchi’s solo as the sphere surrounded her. As she was lying on her back in a semi-arched position, her head was facing the audience. She then pressed up into a high-arched position without using the support of her hands–a move which demonstrates the serious strength and athleticism of the Diavolo dancers. Lastly, one of my favorite movement phrases was the duet performed by Leandro Damasco and Ezra Masse-Mahar. The flawless ascension and decent to the floor, their use of partner work, and unparalleled control over their bodies was unreal. They danced as though they were perfect mirror images of each other.

The architect of motion, Jacques Heim, and his team of construction workers with Diavolo provided the most unique blend of theater production, storytelling, movement vocabulary, and pure art, while the architect of the atmosphere, Bramwell Tovey, provided a tenuous yet hypnotic environment with Glass’s music, courtesy of the pared down string orchestra of LA Phil members. I look forward to seeing Fluid Infinities again as well as the complete trilogy, L’Espace du Temps, in the future.

photos by Mara Zaslove

photos by Mara Zaslove

staff photographer for Diavolo Dance Theater

Fluid Infinities

Diavolo Dance Theater

part of Music by Glass – Dance by Diavolo

LA Phil at the Hollywood Bowl

played Thursday September 5, 2013, 8:00PM

ARTISTS:

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Bramwell Tovey, conductor

Diavolo Dance Theater

PROGRAM

ADAMS: The Chairman Dances Program Notes

PROKOFIEV: Romeo and Juliet Suite

GLASS: Symphony No. 3 / Fluid Infinities (LA Phil-commissioned world-premiere choreography)

for more info on this and future events, visit LA Phil / Hollywood Bowl

for more info on Diavolo Dance Theater, visit http://www.diavolo.org/