WHAT A RUSH

One day soon, or so we’re told, we will no longer drive. At the edge of the Age of the Driverless Car, taking a spin behind the wheel will become a thing of an increasingly distant past. Trendsetters assure us that this is the next great advance in safety and transportation. Soon we won’t be a captain at the wheel but a passenger back in the hold of the ship.

If this is true, then driving will be only a quaint memory centuries into the future. Tomorrow’s children will be surprised that we ever took part in such a barbaric habit with such deadly results. They will look at traffic deaths the way we look at dueling. That is, if they even know about driving at all.

This choice will soon enter the marketplace, and I’m not quite sure which way it will go. Should we accept the common virtue of safety? Or will we reject the disappearance of the human element? Will we be too stubborn to lose the thrill?

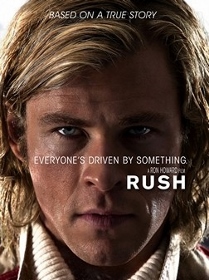

Pushing toward that thrill is at the axis of Rush, Ron Howard’s superb film about Formula 1 racing of the seventies. At the end of the push, Peter Morgan’s script suggests, is ecstasy or mortality. That push is at the center of the rivalry between two legendary world champions from that era.

The popular, dashing Brit James Hunt (Chris Hemsworth in a star-making role) was the epitome of the playboy racer – a lady killer living for the thrill from track to track, bottle to bottle and bed to bed. Women stop when he walks into a room. Overwhelmingly talented and slightly reckless, Hunt may be the guy for whom things come too easy, always at risk of wasting away.

Niki Lauda (German actor Daniel Brühl), his Austrian nemesis, is not in the adventure. His strengths are mathematical and analytical – he is a master at engineering a car to trim precious seconds. Poisoned at birth by shortness and an overbite, rejected by his wealthy father, the chip on his shoulder makes him feared and hated. Down deep, Lauda looks at outlasting his enemies as victory.

Rush tracks the rivalry from minor league races in the early 70s and builds to the tense, exciting and ultimately catastrophic 1976 Formula 1 season. Hunt and Lauda wouldn’t know it at the time but they were racing toward separate, unexpected destinies, the sort that would leave them permanently changed.

What makes Rush successful is how easily Howard and Morgan resist the easy assignment of hero and villain. The story has Ben-Hur and Masala written all over it; all it needs are spikes on the wheels. Brühl burns charisma, and Hemsworth plays up Hunt’s thrill-a-minute personality and carnal irresistibility even as the filmmakers sharply present him as a man who came close to wasting his talent.

The real strength is the way it builds sympathy for the misunderstood Lauda. His personality and appearance make him an easy villain. And yet you see virtue in his determination to make the best of himself in a world that seems angled against him. In the end, the film identifies a surprising well of decency and commitment to other people, one that leads Lauda to a fateful choice at the end.

Rush is Howard’s best film in some time, one of the occasions when his above average craftsmanship and willingness to explore visually align with the story being told. While the look seems unnecessarily oversaturated (director of photography Anthony Dod Mantle), it is helped by a super-charged sound design for the races (score by Hans Zimmer, sound design by Markus Stemler). Rush is a tremendous example of the sort of intelligent film that Hollywood resources can make but too rarely do.

photos courtesy of Universal Pictures

Rush

distributed by Universal Pictures

Cross Creek Pictures and Exclusive Media

produced in association with Revolution Films and Imagine Entertainment

rated R; running time 123 min

opens September 27, 2013 in wide release