SITE-SPECIFIC IS NOT SO SPECIFIC

La Jolla Playhouse supported the trend of site-specific and immersive theater by presenting a four-day program of over 20 different performances in and around the Playhouse. The WoW (WithOutWalls) 2013 festival was a beehive of activity which sadly played only one weekend. It was an arena for nurturing and showcasing  artists who are rethinking theatrical boundaries outside of a proscenium arch. Music, dance, theater, multi-media and performance art from local and visiting artists took place in arenas as disparate as an elevator, a lawn, beach cliffs, sculptures and, surprisingly, inside an actual theater. The excitement on campus was palpable for this celebration of both community and theater. Simultaneous performances occurred amongst throngs of people who milled about. Indeed, right next to food trucks and a beer garden with live musicians, I espied audiences following the Spanish theater company Kamchà tka’s suited actors improvising and carrying suitcases.

artists who are rethinking theatrical boundaries outside of a proscenium arch. Music, dance, theater, multi-media and performance art from local and visiting artists took place in arenas as disparate as an elevator, a lawn, beach cliffs, sculptures and, surprisingly, inside an actual theater. The excitement on campus was palpable for this celebration of both community and theater. Simultaneous performances occurred amongst throngs of people who milled about. Indeed, right next to food trucks and a beer garden with live musicians, I espied audiences following the Spanish theater company Kamchà tka’s suited actors improvising and carrying suitcases.

Productions under the banner of site-specific theater (which typically takes place in existing spaces, such as a bar in It Is Done) and immersive theater (which is developed in a manufactured environment, such as the hotel of Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More) are quickly gaining ground. One reason, I surmise, could be that live performances are battling with the internet’s popularity: The performing arts need audiences, and audiences are intrigued by the notion of interacting with the production–so much so that they’ll even stomach tripe like Tony and Tina’s Wedding, where you are a guest at an American-Italian reception during which the  audience is served a meal and interacts with the actors (it is largely attended by tourists, bachelorette parties, and members of the Red Hat Society).

audience is served a meal and interacts with the actors (it is largely attended by tourists, bachelorette parties, and members of the Red Hat Society).

As with last week’s international theater festival, RADAR L. A., WoW displayed a dizzying array of creative endeavors (which I lump together as “interactive theater”), including Seafoam Sleepwalk, a new piece from Basil Twist which included a giant puppet emerging from the ocean (literally); the Australian group Polyglot’s “We Built This City,” an interactive playspace where cardboard cities are constructed and then torn down; and the ever-popular Car Plays: San Diego’”five ten-minute playlets occurring inside actual cars.

I can’t speak to the success of so many individual works, but it’s a given based on the multitude of theater festivals I’ve attended that the quality will be spotty at best. But as with the theatrical landscape itself, there is always one or two which deserve an afterlife’”although it’s usually the best-funded or best-promoted works that move on. Even the thrilling Car Plays, which I saw last year, had an uneven quality within the greatest theatrical construct ever witnessed. With all of the experimental goings on, and only one spot available in an already crammed schedule, I chose to see Tom Dugdale’s production of Our Town.

Why? The script.

From New York (Then She Fell) to Los Angeles (The Manor) to Chicago (The Madness of Edgar Allan Poe) to Oregon Shakespeare Festival (Willful), theater practitioners are experimenting with the notion of one’s relationship to his or her physical environment. But much more often than not, the gimmickry of the event often trumps the bad playwriting and/or mixed acting and a general pretentiousness. As such, these “events” are rarely thought-provoking and fail to move or touch me emotionally. As with conventional theater, the most successful shows are those with a strong script and potent performances, such as Off-Broadway’s Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812. (Only once did I see a successful production which had a great script and not-so-great performances: We Players’ Macbeth may have sacrificed storytelling for staging, but as presented in Fort Point underneath the Golden Gate Bridge it was a thrilling environmental tour-de-force.)

From New York (Then She Fell) to Los Angeles (The Manor) to Chicago (The Madness of Edgar Allan Poe) to Oregon Shakespeare Festival (Willful), theater practitioners are experimenting with the notion of one’s relationship to his or her physical environment. But much more often than not, the gimmickry of the event often trumps the bad playwriting and/or mixed acting and a general pretentiousness. As such, these “events” are rarely thought-provoking and fail to move or touch me emotionally. As with conventional theater, the most successful shows are those with a strong script and potent performances, such as Off-Broadway’s Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812. (Only once did I see a successful production which had a great script and not-so-great performances: We Players’ Macbeth may have sacrificed storytelling for staging, but as presented in Fort Point underneath the Golden Gate Bridge it was a thrilling environmental tour-de-force.)

Widely-produced, Thornton Wilder’s Our Town is a flawless script. The three-act play (“Daily Life,” “Love and Marriage,” “Death and Eternity”) brilliantly manages to be both sentimental and matter-of-fact. A Stage Manager/Narrator leads us  through the early twentieth-century story of the denizens of small-town Grover’s Corners, centering on their everyday lives and the relationship of high school sweethearts George and Emily.

through the early twentieth-century story of the denizens of small-town Grover’s Corners, centering on their everyday lives and the relationship of high school sweethearts George and Emily.

University of California, San Diego M.F.A. graduate Tom Dugdale conceived and directed the play under the auspices of THE TRIP, a new theatrical impulse (I’m not even sure what that means) founded in San Diego by Joshua Kahan Brody and Dugdale (La Jolla Playhouse is located on the UCSD campus and Dugdale is also an associate producer of WoW).

Wilder calls for no props or scenery, but Act I begins with the actors as a group of animated young friends who invite us to sit in lawn chairs and join their summer picnic, which includes unlimited free soda pop. There are props aplenty on a long  picnic table, but they are part of this barbeque populated by twentysomethings.

picnic table, but they are part of this barbeque populated by twentysomethings.

Wilder’s metatheatrical devices are intensified as the players kid with each other about their individual portrayals of a milkman or newspaper editor. After allusions to modern life and a few guitar-accompanied songs, the earnest gang begins to settle into character. Eventually, we no longer see them as young actors; we buy them as parents, professors, etc. This reminded me of Elevator Repair Service’s Gatz, in which office workers reading The Great Gatsby eventually become the characters from the book.

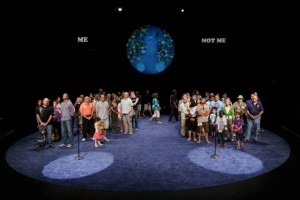

The audience was moved en masse carrying our chairs to another spot with the imposing back wall of the Forum Theatre situated behind a makeshift platform stage. Dugdale than incorporated multi-media video (to “preserve the evening” the program states): Actors projected coupled members of the audience onto the back wall. It all seemed a bit obvious (“This is all Our Town”), but once the camera fixated on George and Emily’s hands barely touching each other in the Act II ice  cream shop scene, there was an emotional effectiveness the likes of which I have never seen before in this play.

cream shop scene, there was an emotional effectiveness the likes of which I have never seen before in this play.

Unfortunately, Dugdale’s device of getting deeper into the play backfired upon entering the theater space inside Galbraith Hall. The Act III scene, which takes place in a cemetery inhabited by characters that died in the nine years since Act II, is extraordinarily tricky to play. Dugdale was smart to steer from multi-media in this black box space, where strategically lit characters sat alongside audience members (I get it: “We are all in this cemetery together”), but actors were either obliterated, inaudible or so emotionally over-the-top that the enterprise ended up as heavy-handed and obscure.

Still, there were some astoundingly effective moments and even with spotty portrayals the exuberance of the cast could be infectious. All graduates or current students of UCSD, they were Elisa Benzoni, Joshua Brody, Carissa Cash, Zoë Chao, Tom Dugdale, Lauren Juengel, Claire Kaplan, Matthew MacNelly, Jack Mikesell,  Thomas Miller, Jenni Putney, Patrick Riley, Taylor Shurte, Bo Tindell, and Ian Wallace.

Thomas Miller, Jenni Putney, Patrick Riley, Taylor Shurte, Bo Tindell, and Ian Wallace.

After Our Town, I was able to fit in Platonov, Jay Scheib’s adaptation of the Chekhov play using a custom-built one-bedroom house in which actors were simultaneously displayed on a giant drive-in movie screen. You can’t imagine a more inventive set-up. Unfortunately, we were forced to watch the screen most of the time, and the seemingly endless show was plodding, meandering and distancing. For all of its missteps, at least Our Town managed to grab our hearts.

So as we traipse further into an ever-shifting medium, it appears that a majority of interactive theater is largely an experimental platform for artists. It’s also a commodity used to attract new audiences, just like the proliferation of jukebox musicals and shows with the technical wizardry required to distract from bad writing. All of these seem to be here to stay, but while jukebox musicals will always pander to the lowest common denominator, site-specific and immersive theater is still in flux. In the end, I fear that these forms of interactive drama are like changing outfits when it is the body underneath which needs reexamining.

In the meantime, WoW is highlighting the form itself. This festival is extremely valid and important as a well-funded think tank, and the La Jolla Playhouse is to be commended for sponsoring such an event.

photos by Daniel Norwood, Jim Camody and James Hebert

Our Town, Platonov

part of the Without Walls (WoW) Festival

La Jolla Playhouse

played October 3-6, 2013

for more info and future events, visit http://www.lajollaplayhouse.org/