MOZART’S SISTER: POSSIBLY MORE TALENTED, DEFINITELY BETTER LEGS

In many one person shows that are biographies of historical personages, there’s the risk of Wikipedia syndrome, in which the performer essentially just narrates the events of her character’s life, as though they’ve just been dictated straight from some website chronology. Fortunately, writer-performer Sylvia Milo’s luscious depiction of the life of Wolfgang Mozart’s lesser known sister Nannerl eschews the dreaded bio-adaptation problem – and it does so with class and evocative energy. In Isaac Byrne’s elegantly minimalist production, the life of Mozart’s older sister is recounted with graceful sophistication. Milo’s narrative is a surprisingly deep and penetrating analysis of the life of Wolfgang’s older sister, who could have been her older brother’s equal – if only she hadn’t been born a woman. Here is a story of a tragic heroine, presented as feminist parable; the tale of one of history’s great “might have beens,” the victim of her time and of her cultural milieu.

As a child, Nannerl dazzles her stern music teacher dad with her ability to play the harpsichord. Indeed, she is the apple of her dad’s eye and the promising musician in the family – until her infant sibling “Wolfie” is old enough to play the instrument himself and proves himself to be a genius prodigy. Dad takes his kids on a tour of the European capitals, where Nannerl and Wolfgang perform together as a sort of novelty act before kings and cheering crowds.

As a child, Nannerl dazzles her stern music teacher dad with her ability to play the harpsichord. Indeed, she is the apple of her dad’s eye and the promising musician in the family – until her infant sibling “Wolfie” is old enough to play the instrument himself and proves himself to be a genius prodigy. Dad takes his kids on a tour of the European capitals, where Nannerl and Wolfgang perform together as a sort of novelty act before kings and cheering crowds.

However, as Nannerl enters puberty, she is not allowed to train or to learn composition; instead, Wolfgang gets those treats while she is forced to learn needlepoint, housewifery and other homely tasks to prepare her for her assigned avocation as a bride. As Wolfgang’s career skyrockets, Nannerl privately practices her music and teaches music, ultimately being forced to marry a pompous, arts-hating Baron. Forced to endure reading about the endless triumphs of her younger brother from afar, and then watching as she herself is essentially pushed to the side of her own life, Nannerl’s existence is not a happy one, even though she outlives her famous brother by many decades. She ends her life disappointed and deprived of the spotlight and the opportunities, due to her gender.

Milo recounts her character’s tale in the first person, in a performance that is beautifully subtle and sad, with more than a touch of ironic despair. She smiles throughout, but it doesn’t take long before we realize that Milo is one of those performers who has the innate ability to convey great sorrow through a beautiful, gentle expression. It’s clear that she is also an excellent dancer: Her gestures have a balletic, acrobatic quality, and there are times when a movement possesses kabuki-like dimensions of meaning. She sometimes resembles the dancing girl in the  center of a music box, an impression that’s underscored by Nathan Davis and Phyllis Chen’s tinkling score. At one moment, she bends over backwards stretching like bamboo in the wind as her character desperately strives for the artistic validation that will never be hers.

center of a music box, an impression that’s underscored by Nathan Davis and Phyllis Chen’s tinkling score. At one moment, she bends over backwards stretching like bamboo in the wind as her character desperately strives for the artistic validation that will never be hers.

This sort of show inevitably contains echoes of Shaffer’s Amadeus, particularly during scenes in which Nannerl voices outright envy over the glittering prizes her brother achieves with such comparative ease. Wolfgang’s well known love of scatology and infantile jokes are described as well, but Nannerl’s relation to her sibling’s sense of humor is surprisingly complicated: She laughs and smiles when Wolfgang’s dirty gags are used to help bond her to him, but her enjoyment of the dirty jokes turns to disapproval when it’s clear that Mozart’s ultimate wife Constanze supplants her in his attentions.

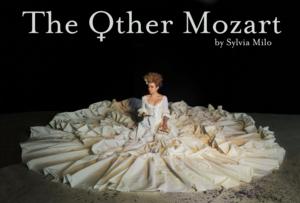

Director Byrne places Milo atop a gigantic 18th-century woman’s dress, designed by Magdalena DÄ…browska, spread to cover the stage, which is festooned with musical scores and pieces of instruments as though the actress is imprisoned on a huge quilt. As the story unfolds, the dress set becomes a symbol of the restrictive world to which Maria must accommodate herself. In one of the play’s final scenes, Milo literally buttons herself into a restrictive metallic corset (panier/corset sculpture designed by Miodrag Guberinic) that sticks out of the dress, imprisoning herself in the gown; she is able to move only slightly. It’s a powerful coda, and one which intensely articulates the play’s theme of a thwarted female’s repression. Nannerl Mozart might never have had her brother’s career or talent, but she never had the opportunity to prove it, either. Milo’s text suggests that the world was deprived of a great musician for the sake of forcing someone to be a mediocre housewife.

photos by Daniel Murtagh and Peter Griesser, DIVA Arts Collective

The Other Mozart

reviewed at the All For One Festival

Cherry Lane Studio Theater

international tours continue; for dates and cities, visit The Other Mozart