THE SHACKLES OF RADIO ARE LOOSENED A BIT FOR THE STAGE

Michael Gambon is tremendous in Trevor Nunn’s staging of Samuel Beckett’s radio play All That Fall. The drama, first performed on BBC radio in 1957, follows septuagenarian Mrs. Rooney (Eileen Atkins) as she walks from her home to the train station to pick up her blind husband Mr. Rooney (Gambon) on his birthday; we stay with the couple as they make their trek home.

On her way to the station Mrs. Rooney meets Christy (Ruairi Conaghan), who tries to sell her a quantity of dung from a cart strapped to a reluctant hinny; Mr. Tyler (Frank Grimes), who tells her about his daughter’s hysterectomy and whose bicycle has a flat rear tire; and Mr. Slocum (Trevor Cooper), who gives Mrs. Rooney a ride to the station in his tiny automobile, into which he must unceremoniously stuff her from behind.

On her way to the station Mrs. Rooney meets Christy (Ruairi Conaghan), who tries to sell her a quantity of dung from a cart strapped to a reluctant hinny; Mr. Tyler (Frank Grimes), who tells her about his daughter’s hysterectomy and whose bicycle has a flat rear tire; and Mr. Slocum (Trevor Cooper), who gives Mrs. Rooney a ride to the station in his tiny automobile, into which he must unceremoniously stuff her from behind.

At the station we meet Tommy (Billy Carter), who helps Mrs. Rooney out of the car, the stationmaster Mr. Barrell (James Hayes) who asks about her health, and religious spinster Miss Fitt (Catherine Cusack), who assists Mrs. Rooney up the steps to the platform because it is “the Protestant thing to do.†The train is late but finally arrives and Mrs. Rooney’s husband is delivered to her by Jerry (Liam Thrift), a helpful boy whom Mr. Rooney instructs his wife to tip a penny.

There are excellent reasons to see this show: The play itself is a masterpiece that is unlikely to be performed very often – due in part to the virtual extinction of radio theater and in part to the restrictions placed on its staging by Beckett’s estate; Mr. Gambon, who should never be missed in anything; Ms. Atkins, who delivers a rich,  multi-layered portrayal; and the rest of the cast, all of whom turn in unassailable performances.

multi-layered portrayal; and the rest of the cast, all of whom turn in unassailable performances.

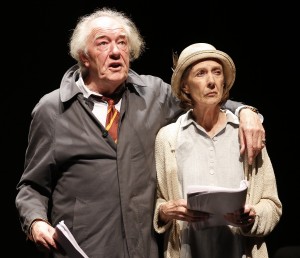

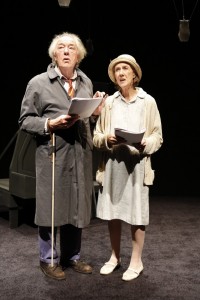

Unfortunately Mr. Nunn’s staging of All That Fall, while masterfully executed, is conceptually flawed. On the one hand, it’s as if we are watching actors reading the radio play, with 1950s-style microphones hanging from the ceiling of Cherry Truluck’s set, and performers sitting on chairs waiting for their turn to get up and “read†from the scripts they’re holding. On the other hand, Mr. Nunn has costumed the performers not in what actors from the 50s would be wearing to a radio studio, but in the clothes of the townspeople in the play.

Players perform some of the actions and pantomimes suggested by the script but not others, and the performers are not always in sync with Paul Groothuis’s sound effects. Nunn seems to be attempting to make a show that is one part actors playing actors doing radio theater in a studio, and another part actors performing the play  as the characters. The result is two concepts, neither fully realized, which together do not add up to a complete whole.

as the characters. The result is two concepts, neither fully realized, which together do not add up to a complete whole.

The fault here is partly Beckett’s. Most regrettably the playwright—now his estate—provides strict stipulations which make it impossible to perform All That Fall as a straightforward play; apparently he meant for it to be heard, not seen. Loopholes in the provisions have made its staging possible, but Nunn is forced to work within such severe limitations that his solutions are unsatisfying. Perhaps it would be better just to have actors read the play without attempting to theatricalize it, at least until the copyright runs out.

Possibly as a consequence of Nunn’s attempt to create a visual theatrical experience, the first half of the performance, before the appearance of Gambon, feels a bit drawn out. When he does take the stage, the show gets a shot of adrenaline. But this flowering, ironically, is also not without its thorn. All the performances here are at the very least solid, and yet when Gambon appears, he’s like a tidal wave sweeping  everything around him, and everything that came before, off the stage. This is not to say that he makes a spectacle of himself or tries to undermine or overshadow the other performers, not at all; his interactions are perfectly organic.

everything around him, and everything that came before, off the stage. This is not to say that he makes a spectacle of himself or tries to undermine or overshadow the other performers, not at all; his interactions are perfectly organic.

It’s simply that his presence and power—his genius—are too bright for the other players. He’s the only one who appears actually to be reading the lines from his script, at one point even getting lost in the text—thereby adding to the illusion that this is a radio play reading—whereas the other actors look like they have their lines memorized and appear to be using their scripts as mere props.

Gambon also does some remarkable things with his fingers and hands; just from looking at them we can see a character nervous, high-strung, powerful, old; if all we could see of him were his wrists, that would be enough to tell much of the story. But in fact it’s as if every part of him is animated and performing independently but toward the same purpose, like a symphony orchestra. The other actors, good as they are, can’t keep up, and this dichotomy creates an imbalance.

Gambon also does some remarkable things with his fingers and hands; just from looking at them we can see a character nervous, high-strung, powerful, old; if all we could see of him were his wrists, that would be enough to tell much of the story. But in fact it’s as if every part of him is animated and performing independently but toward the same purpose, like a symphony orchestra. The other actors, good as they are, can’t keep up, and this dichotomy creates an imbalance.

Whatever flaws this production has, in the grand scheme they are relatively minor, and there’s enough excellence on display to more than warrant a viewing.

photos by Carol Rosegg

All That Fall

Richard Darbourne Ltd and Jermyn Street Theatre

in association with Gene David Kirk

59E59 Theaters

scheduled to end on December 8, 2013

for tickets, call (212) 279-4200 or visit www.59e59.org