UPDATING THE OLD, PRESENTING THE NEW

As part of the North American tour celebrating its 45th season, the Lar Lubovitch Dance Company arrived at Valley Performing Arts Center last Saturday with a program of mostly newer works and some older duets.

As part of the North American tour celebrating its 45th season, the Lar Lubovitch Dance Company arrived at Valley Performing Arts Center last Saturday with a program of mostly newer works and some older duets.

With Picasso’s 1905 Family of Saltimbanques as inspiration, we are taken through the creative process, performance and lifestyle of traveling artists in Transparent Things (2012). Created during Picasso’s “Rose Period,” the painting portrays itinerant circus performers in a desolate landscape, and Lubovitch softly explores the imagined relationships and motivations of the painting’s six people. Wearing Reid Bartelme’s costumes splashed in splendidly subdued colors (loyally reimagining those in Picasso’s work), the dancers whirl about the stage in characters that are both frisky and longing. We see them rehearsing, stretching, entwining, and clasping hands as their bodies are blown around, representing their peripatetic existence.

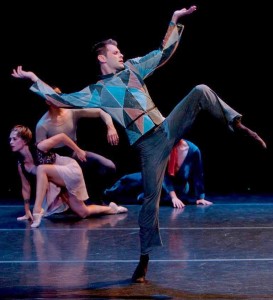

Occasionally, the troupe took on the flavor of Russian peasants, and the lithe Attila Joey Csiki had a lovely solo like a rag doll come to life. Almost emulating the puppet known as petrushka (a harlequin-like stock character in the vein of commedia dell’arte), Csiki was interchangeably silly and sorrowful in temperament, and his astounding body control gave the appearance that he was actually being maneuvered by strings.

While the ethereal nature of art was lovingly explored in the dichotomy between flurries of movement and fascinating tableaux vivants, the stage seemed curiously void. The Lubovitch touch that filled the playing area in his story ballet, Othello, was missing here. Compounding that was the problematic sight lines for the Valley Performing Arts Center’s center section, which curiously does not have a rake. The tiny woman in front of me blocked the stage floor, so the lovely scene involving the troupe on the ground greeting the day was blocked (many patrons moved to side seats after this opening piece for a clearer view).

What did make us sit up and take notice, however, was the live accompaniment of Debussy’s 1893 String Quartet in G Minor. Sitting stage left, the Bryant Park Quartet (Anna Elashvili and Ben Russell, violins, Nathan Schram, viola, and Tomoko Fujita, cello) executed this impressionistic masterwork with such precision and virility that they could easily headline at Carnegie Hall. When the dancers moved tenuously towards the musicians and surrounded them (with one even resting against the cello), it was a blending of two art forms that was truly lovely.

A triad of duets followed the first break. Lubovitch reconfigured his own choreography from his Fandango (1989, originally set to Ravel’s Bolero), commissioned an original score by Randall Woolf (prerecorded with vocalist Mellissa Hughes and guitarist Gyan Riley), and came up with Vez. As passionate as the flamenco-tinged music which accompanied them, Nicole Corea and Clifton  Brown exuded fervent, earthy devotion as they tested the strength of each other’s bodies. Their unassertively acrobatic acts of lovemaking included rolling over one another and Brown actually stepping on Corea. Their interlaced writhing and zealous movements inflamed the senses.

Brown exuded fervent, earthy devotion as they tested the strength of each other’s bodies. Their unassertively acrobatic acts of lovemaking included rolling over one another and Brown actually stepping on Corea. Their interlaced writhing and zealous movements inflamed the senses.

While Vez celebrated a gypsy passion, it was smooth compared to The Time Before the Time After (1970), Lubovitch’s examination of a sadomasochistic relationship. Katarzyna Skarpetowska in a slip and Reed Luplau in pajama bottoms begin in a gentle embrace but soon she tries to break away and he goes to hit her. Instead of running away, she returns for more of that obsessive, raw lovemaking, evidenced in a series of powerful lifts. At one point, he appears like James Cagney smashing a grapefruit into Mae Clark’s face. The sexual tension in Vez was milquetoast compared to this, which teems with viciousness and a plea for more, complimented by the harmonic friction of Igor Stravinsky’s Concertino for String Quartet

Concerto Six Twenty-Two (1986) is one of the most exquisite and eloquent responses to the AIDS epidemic ever choreographed. Using Mozart’s affectionate and haunting Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra, this work focuses on accord, support, and fraternity. Two males clad in white trousers and polo shirts slowly approach each other and execute sweeping arm movements that culminate in intertwining circles. Soon, they are slowly, gracefully balancing against each other, melting into a classically flowing pas de deux. The solo variations are made highly emotional by one partner spotting the other, highlighting the fact that self-expression is empowered when sustenance is offered by another. Never for a moment does this elegant work feel effeminate.

Csiki again seemed positively weightless executing graceful swoops and turns, but Tobin Del Cuore, attractive and larger in build, was not a well-suited partner. This piece–with its running, twirling and catching–screams for a couple similar in stature. It’s one of those instances in which the lifts are performed beautifully but sadly remain earthbound, making this a lovely rendition that misses the opportunity to be transcendent. In addition, all three duets were strangely performed well back in this very deep stage; that the dancers did not move downstage towards the proscenium is a head-scratcher.

The final piece, Crisis Variations (2011) at first seemed like a piece choreographed by dancers for dancers, as we are immediately bombarded with visual cacophony which was difficult to discern. But the tension, scurrying and ostensible lack of control grew into a jazzy and combustible display presenting a picture of today’s hectic lifestyle, as if pedestrians on a New York street danced with wild abandon to the severe musical suite by Yegeniy Sharlat, taken from Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes for Piano.

The seven-member ensemble created ambivalent moving statuettes both savage and agile, giving way to a duet between Skarpetowska and Brian McGinnis, who dragged her on her knees like a caveman claiming his possession. Still somehow, this moody piece’”however much it highlighted society’s breakdown and showcased Lubovitch’s trademark ability to meld styles’”was almost too chaotic to resonate and ultimately wasn’t nearly as rough as the lovers in The Time Before the Time After.

photos by Steven Schreiber, Paula Lobo and Andrea Mohlin

Lar Lubovitch Dance Company

Valley Performing Arts Center in Northridge

played on November 23, 2013

for future VPAC shows, call (818) 677-3000 or visit VPAC