AN ANIMATED AND LIVELY FLUTE

The Magic Flute was written specifically for the common man, and thus was structured as an exaggerated amusement so that special effects could be employed. Mozart’s accessible music is among the most popular in the repertoire; it’s youthfully melodious  yet stretches for transcendent classicism. Emmanuel Schikaneder’s libretto is known as Singspiel, which has characters talking as well as singing; he interchanges a fairy-tale journey right out of Disney (or German make-believe á la the Brothers Grimm) with dark Masonic rituals (there are Three Ladies, Three Boys and Three Trials), devout religious allusions, and comical frolics right out of an 18th-century Viennese puppet show. (With gods such as Osiris and Isis referred to in the libretto, ancient Egypt was also in mind, but rarely is The Magic Flute set in the land of Pharaohs as Aida is).

yet stretches for transcendent classicism. Emmanuel Schikaneder’s libretto is known as Singspiel, which has characters talking as well as singing; he interchanges a fairy-tale journey right out of Disney (or German make-believe á la the Brothers Grimm) with dark Masonic rituals (there are Three Ladies, Three Boys and Three Trials), devout religious allusions, and comical frolics right out of an 18th-century Viennese puppet show. (With gods such as Osiris and Isis referred to in the libretto, ancient Egypt was also in mind, but rarely is The Magic Flute set in the land of Pharaohs as Aida is).

There are traditional and timeless elements in the story (more like a medley of events) that validate why Disney remains a permanent fixture in our world: There’s the Queen of the Night, whose daughter has been kidnapped by a high priest; a prince who battles a dragon and is then enlisted to free the princess; supernatural creatures; a bird-catcher who is normally bedecked in feathers; and a series of trials which lead to enlightenment. It’s pure adventure with loads of mysticism, and the patchwork of events range from bawdy farce to transcendent solemnity.

That is why, since its premiere in 1791, Flute has been wide open to interpretation. Production concepts have been as varied as outer space, a Wild West saloon, a hippie commune and, in Kenneth Branagh’s cinematic adaptation, the trenches of World War I.

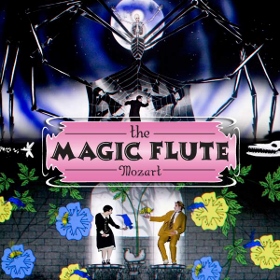

In a new production from Berlin’s Komische Oper which arrived courtesy of LA Opera at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, directors Suzanne Andrade and Barrie Kosky not only present the visuals like a silent film replete with animation, but have reconfigured the often tedious spoken dialogue with projected titles of text that mimic placards from live-action silent movies. The results’”colorful, clever, and quite gorgeous’”make this technologically daring wonderment a cross between an opera and the gag cartoons of the 1920s. It is also the first must-see opera of the year.

Created by the British theater collective “1927” (named after the year of The Jazz Singer’s release), animation designer Paul Barritt’”who leads the company with Andrade’”clearly draws from filmmaker Georges Méliès, German Expressionism, Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python’s Flying Circus animations, and the work of Ub Iwerks, who singlehandedly drew the first Mickey Mouse cartoons. Barritt mimics the naïve style of 1920s cinema, opting for line drawings over realism, and actors interact with the graphics, which are projected onto a flattened wide screen (there are no set pieces, just revolving doors and ledges). The whimsical quirkiness actually pulls out the magic and beauty of the music.

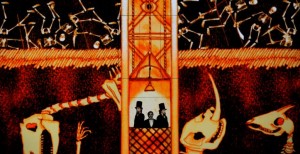

Normally, I can’t stand when opera singers just stand and deliver. For once, I was overjoyed that the singers at hand did not move because the animation did the moving for them (to be fair, the cast vigorously dashed from one spot to another, and some had to run in place as well). Not one vocalist had an off-night, but truly I think the delightful animations were the star of the show. Slightly problematic was that the visuals filled the stage, but the voices didn’t always fill the house (an energetic orchestra assertively led by James Conlon sure did). The Three Boys’”trebles Drew Pickett, Charles Connon, Jamal Jaffer’”who guide our heroes on their journey, sounded terrific, but their volume was better-suited for a church. Likewise bass Evan Boyer as the high priest, Sarastro, who now appears as a fin de siècle Jules Verne in black top hat, gloves and frock coat; Boyer’s low notes sounded like they were coming from another room (as his two armored men, Valentin Anikin and Vladimir Dmitruk projected their mellifluous voices into next week).

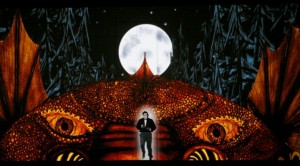

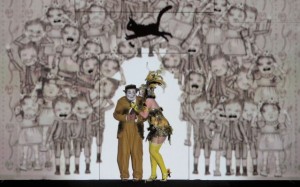

Papageno, the bird-catcher, is now a Buster Keaton-type clown who is tailed by an angular black feline, reminiscent of George Herriman’s comic-strip, Krazy Kat. As Papageno, Rodion Pogossov’s rich voice matched his expressive facial clownery. The Queen of the Night is now a gargantuan, fuming spider, her energetic legs spreading out over the entire wall. Erika Miklósa sang the Queen’s famous aria “Der Hölle Rache” with requisite crispness and agility (although for the life of me, the bouncy music never sounds like Hell’s vengeance is boiling her heart).

Prince Tamino, powerfully realized by even-toned tenor Lawrence Brownlee, appears in whiteface and a tuxedo. A highlight is when he is actually swallowed by a dragon and ends up surrounded by bones in its stomach (I also loved when he declared his love for the princess Pamina, and anatomically correct hearts fluttered across the screen). As Pamina, soprano Janai Brugger, dressed in a black Victorian gown and a Louise Brooks bob, was flawless throughout–and a highlight of the show; there was eloquence in her severely held stances and fixated stares as she made delicate the high passages in her notoriously difficult aria about vanished love, “Ach, ich fühl’s.”

As Sarastro’s slave Monostatos, tenor Rodell Rosel was delightfully and rightfully creepy in his Nosferatu getup, and the Three Ladies (hysterically sung by Hae Ji Chang, Cassandra Zoé Velasco, and Peabody Southwell) looked like they popped out of a Weimar-era film in Esther Bialas’ spectacular outfits.

As Sarastro’s slave Monostatos, tenor Rodell Rosel was delightfully and rightfully creepy in his Nosferatu getup, and the Three Ladies (hysterically sung by Hae Ji Chang, Cassandra Zoé Velasco, and Peabody Southwell) looked like they popped out of a Weimar-era film in Esther Bialas’ spectacular outfits.

As far as I can tell, there’s no deeper meaning in this production, which is fine with me (although I did wonder why the final chorus is sung without animation in front of a red curtain). Some of the story is sacrificed to the truly spectacular animated manifestations, and there are a few draggy moments, but this may be the perfect introductory opera for your kids. This endlessly innovative production is jam-packed with surprising and funny moments. And, yes, the flute, now an animated naked sprite, is as magic as the title suggests.

photos by Robert Millard

The Magic Flute

presented by Los Angeles Opera

1927 Theater Company at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion

scheduled to end on December 15, 2013

for tickets, call 213.972.8001 or visit http://www.laopera.org/

opens December, 2013

Deutsche Oper am Rhein (Theater Duisburg)

Duisburg, Germany

http://www.rheinoper.de/en_EN/

back in rep from February, 2014

Komische Oper

Berlin, Germany

http://www.komische-oper-berlin.de/en/

opening March, 2014

Minnesota Opera

Minneapolis/St. Paul, USA

http://www.mnopera.org