LEAR, BECAUSE IT’S THERE

A friend commented to me once that as hard to take as Orthodox Jews might seem to us secular ones, it is largely thanks to them and their stubborn adherence to the old ways that the Jewish religion is still around today. Something similar can be said of the practitioners of the Shakespeare religion. We need them to practice their rituals, to keep the faith, even if most of what they produce doesn’t feel like great art – a priest doesn’t have the luxury to do his job only when he feels inspired.

A director staging a Shakespeare play today (as opposed to, say, in the 16th century) has to get so many elements right just to make the thing watchable for the lay viewer that he is deserving of much praise even if the final result isn’t particularly outstanding – praise which today’s viewer is more than happy to furnish. So it is not surprising that a recent performance of King Lear, under Angus Jackson’s competent direction, received a standing ovation. Indeed this is a solid, intelligent, serious production. Mr. Jackson builds a sturdy foundation: The actors make Shakespeare’s language their own and speak naturally about real things, not abstractions; they invest what they say and do with authentic feeling; the story is clearly told and could be followed even without words; the cast mostly fits well together; and there is a consistency of mood. Yet I failed to connect emotionally with much of it, and one reason is that the production lacks that one single distinct point of focus toward which all its other elements should be aimed.

This is immediately apparent in the set and costumes, both designed by Robert Innes Hopkins. The decorations, consisting of a granite and wood floor bordered by huge vertical wooden beams, though textured and weighty, feel spatially unsatisfying, like a picture without a central focal point. Something similar can be said of the clothes. With their heavy fabric and earthy tones, they are too similar to excite the eye and are of limited use when it comes to underscoring the characters’ emotional and spiritual realities. The design goal seems to have been to give the production a medieval, grungy, realistic look (later we will see rain and blood, and hear plucked-out eyeballs hit the floor). But the result is that nothing stands out.

The same can be said of the play’s themes. When staging a revival, a personal vision is essential. And if what one has to say is important and if one has the craft to execute his vision properly the result has the chance of being fresh and unique. Mr. Jackson no doubt has the craft, but I fail to see in his staging some vital vision that he must express. Each theme in the show is given as much weight as another, which makes the production’s dramatic palate muddy, much like the costumes – they aren’t gray but they feel like they are.

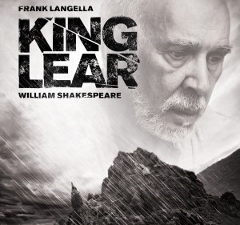

Frank Langella does an excellent job bringing to his King Lear a tragic sense of a once powerful man weighed down and undone, first by old age and then by everything else. When Lear is finally helpless, Mr. Langella’s large and imposing presence deflates into something resembling a scarecrow. He is satisfying to watch, and most of the other actors deliver expert renditions. Denis Conway’s Gloucester is especially memorable; Mr. Conway’s character glows with the integrity and loyalty that end up being his downfall. As admirable as the performances are, there is a certain formality to the acting; one rarely forgets that these are thespians performing Shakespeare.

One of the bigger dramatic problems is caused by the miscasting of Isabella Laughland as Cordelia, Lear’s youngest daughter. What is heart-wrenching in Cordelia’s story is not only that she is an innocent subjected to a tragic fate but that she has within her great love, wisdom, and strength of character – the inner conviction of a truly righteous person doing the right thing – and is punished by life for those virtues. These personal qualities must radiate from Cordelia without words. Ms. Laughland is unable to make that happen.

Mr. Jackson’s King Lear has everything the average theatergoer would expect to find in a Shakespeare play – swords, thrones, costumes, British people, and dialogue that, if you haven’t read the play a couple of times, is difficult to understand. The production is 85% successful in most of its elements. But it’s that last 15% that separates the amazing from the sufficient.

photos by Johan Persson

Additional cast: Sebastian Armesto as Edgar, Steven Pacey as Kent, Catherine McCormack as Goneril, Lauren O’Neil as Regan, Max Bennett as Edmund, Harry Melling as the Fool, William Reay, Rob Heaps, Tom Mothersdale, Chu Omambala, Michael Sheldon, Parth Thakerar, Tim Treloar, Rendah Haywood and Alan Vicary.

King Lear

Chichester Festival Theater

Harvey Lichtenstein Theater at BAM

scheduled to end on February 9, 2014

for tickets, call (718) 636-4100 or visit www.BAM.org