THE BANALITY OF SURVIVAL

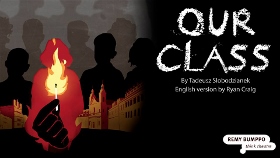

A crowded creation, Our Class remembers the Holocaust by forgetting nothing. Intent on conscience-keeping, burning to reclaim a slice of history, this dogged docudrama, a generous-to-onerous Midwest premiere by Remy Bumppo, is Tadeusz Slobodzianek’s painstaking and pains-giving depiction of genocide in a microcosm (this is no Shoah, the 9-hour, 23-minute 1985 documentary in which a hideous whole is greater than its ugly parts.)

Slobodzianek focuses on 10 classmates in the obscure hamlet of Jedwabne, Poland’”half Catholic, half Jewish’”over the last 70 years. In unmotivated but continual confessions, they narrate, individually and collectively, the children’s torturous evolution from innocent school kids playing games and making fun to a handful of anguished survivors and closeted terrorists, denying, rewriting or, worst of all, reliving a poisoned past.

Indeed, the playwright, who organizes Our Class into 14 “lessons,” confesses his need to chronicle a crime without a statute of limitations: “I don’t know where it began, but I know where it doesn’t end.” How true that proves.

Indeed, the playwright, who organizes Our Class into 14 “lessons,” confesses his need to chronicle a crime without a statute of limitations: “I don’t know where it began, but I know where it doesn’t end.” How true that proves.

Bearing intense witness, artistic director Nick Sandys’ nearly three-hour staging honors a script that lurches and veers from the unmitigated horrors of Schindler’s List and the ironic innocence of The Boy in the Striped Pajamas to soap-opera/sitcom quirkiness and trivial record-keeping. No doubt the author means to honor the highs, middles, and lows of a world turned upside down, as well as the village’s very different occupations by the Soviets, Nazis, and the Soviets again. (A triumphal arch erected by Jewish citizens in 1939’”originally festooned by leftist Polish sympathizers with the hammer-and-sickle to greet Stalin’s troops’”is soon redecorated with swastikas by right-wing nationalists to welcome the German invaders.) But with the Holocaust, a little goes a very long way: Not so ironically in this production, more becomes less.

Only one student, Abram (David Darlow in a plausible state of perpetual duress) escapes to safety in America. From afar this helpless rabbi learns that his entire clan has been wiped out. But, as a kind of retroactive redemption, Abram testifies to the  even greater family he amasses abroad. (On opening night, Abram’s persistent recitation of descendants became unintentionally amusing.)

even greater family he amasses abroad. (On opening night, Abram’s persistent recitation of descendants became unintentionally amusing.)

As for the fate of Jedwabne–not to get drawn into a too-detailed drama–the other nine cohorts end up as divided as the times, with four nasty “Christian” boys helping in 1941 to round up the town’s entire Jewish population of 1,600 into a church (much like similar atrocities in Rwanda). The Jews are incinerated or suffocated, including teenage Dora (Rachel Shapiro) and her baby. The boys make sure that no one lives to tell the tale.

As if rehearsing future evil, Jakub Katz (Aram Monisoff) had earlier been beaten to death in the village square. Only two Jewish children survive: Rachelka (Rebecca Sohn) changes her name to Marianna, converts to Christianity, and marries humdrum but protective Wladek (Matthew Fahey). (Their “forced” wedding is mistakenly played for unnecessary comic relief.) As if to balance Rachelka’s submission, cinema-crazy Menachem (Stephen Spencer) hides away like the Franks in Amsterdam: After the war, this small-town Emile Zola exposes the lie that the Nazis, not the locals, committed Jedwabne’s incendiary mass murder–and fingers the three thug classmates who did. These include the hypocritically pious Heniek (Dennis William Grimes), a priest who should take his own confession over and over.

As if rehearsing future evil, Jakub Katz (Aram Monisoff) had earlier been beaten to death in the village square. Only two Jewish children survive: Rachelka (Rebecca Sohn) changes her name to Marianna, converts to Christianity, and marries humdrum but protective Wladek (Matthew Fahey). (Their “forced” wedding is mistakenly played for unnecessary comic relief.) As if to balance Rachelka’s submission, cinema-crazy Menachem (Stephen Spencer) hides away like the Franks in Amsterdam: After the war, this small-town Emile Zola exposes the lie that the Nazis, not the locals, committed Jedwabne’s incendiary mass murder–and fingers the three thug classmates who did. These include the hypocritically pious Heniek (Dennis William Grimes), a priest who should take his own confession over and over.

For sometimes better but mostly worst, Slobodzianek pursues the biographies of his postwar classmates to today, devoting almost half the play to running recaps of their coping or copping out of the 1941 extermination. Inevitably, what was non-negotiably immediate and seemingly unforgettable in the first act’s anti-Semitic persecution fades before a “T.M.I.” onslaught of updates. (Do we really need to repeatedly learn that Marianna’”who does not revert to her Jewish name’”sublimates her misanthropy over 6 million dead by enjoying 56 channels on her TV, especially the Animal Planet?)

For sometimes better but mostly worst, Slobodzianek pursues the biographies of his postwar classmates to today, devoting almost half the play to running recaps of their coping or copping out of the 1941 extermination. Inevitably, what was non-negotiably immediate and seemingly unforgettable in the first act’s anti-Semitic persecution fades before a “T.M.I.” onslaught of updates. (Do we really need to repeatedly learn that Marianna’”who does not revert to her Jewish name’”sublimates her misanthropy over 6 million dead by enjoying 56 channels on her TV, especially the Animal Planet?)

The collective insanity of the Holocaust can’t be reduced to situational ethics’”“What would you do?”’”incriminating as that seems). However hateful their actions, these townsfolk, whether they followed orders or not, were unforgivable pawns in a bigger  infamy. That perspective, intriguing as the accusations appear, is lost in the second act’s portrayal of personal payback and institutional whitewashing.

infamy. That perspective, intriguing as the accusations appear, is lost in the second act’s portrayal of personal payback and institutional whitewashing.

These cavils aside, Remy Bumppo’s concentrated prosecution of an overlong play delivers solid stagecraft, buttressed by stunning work from 10 driven actors. No question, there’s more than enough truth here to satisfy an audience. Yes, an embarrassment of exposition beats a threadbare text and some stories are more appropriately endured than enjoyed. But Our Class pushes its luck, and an endless epilogue nearly derails a worthy work.

[Editor Note: Click here for a review of another production of Our Class in L.A.]

photos by Johnny Knight

Our Class

Remy Bumppo

Greenhouse Theater Center, 2257 N. Lincoln

scheduled to end on May 11, 2014

for tickets call 773-404-7336 or visit www.remybumppo.org

for info on this and other Chicago Theater, visit www.TheatreinChicago.com

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

It’s curious that you provide a link to a review that seems to be consistent with yours. Why not links to others that disagree to some considerable extent.

Hank:

Since Stage and Cinema is a nationwide site, we add links to OUR reviews of the same play that has been produced elsewhere, regardless of whether or not they are in agreement with the current review. There is no hidden motive. Our readers are serious theatregoers and have told me they enjoy what’s going on in the theatrical landscape – which is why they read reviews of plays produced in other cities (quite a few of our readers do not even live in the major cities we cover).