趙 æ° å¤ å…’ COMES TO A.C.T. AND LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE

Who amongst us can deny that at one time or another we have been wronged or injured by someone else? But how many feel that retaliation by exacting punishment is the only option? Since the dawn of man, revenge has been a double-edged sword: The knee-jerk reaction to commit vengeance against an injustice’”whether real or perceived’”is fraught with moral conflict. Francis Bacon said, “This is certain, that a man that studieth revenge keeps his wounds green, which  otherwise would heal and do well,” and Douglas Horton wrote, “While seeking revenge, dig two graves’”one for yourself.” Prior to his assassination, activist and Rabbi Meir Kahane said, “No trait is more justified than revenge in the right time and place.”

otherwise would heal and do well,” and Douglas Horton wrote, “While seeking revenge, dig two graves’”one for yourself.” Prior to his assassination, activist and Rabbi Meir Kahane said, “No trait is more justified than revenge in the right time and place.”

Revenge is at the heart of The Orphan of Zhao, a 13th-century Chinese play with songs attributed to Jing Junxiang. While this, the earliest known version, dates back to the Yuan dynasty (roughly the age of Chaucer), the historical events it describes date back two millennia before that, between 800 and 600 B.C. The story begins with a massacre in which almost an entire clan is wiped out by a power-hungry minister. When two babies are switched, the orphan of the clan, the sole surviving Zhao, is adopted by the very minister responsible for the massacre. As the orphan comes of age, he learns that his adoptive father is the murderer of his clan.

The central story is so compelling, and the universal themes of Confucian morality, loss, and self-sacrifice are so timeless that The Orphan of Zhao has been translated and amended’”sometimes with radical adjustments to the plot’”for centuries: Adapted into French in 1731 as L’Orphelin de la Maison de Tchao by a Jesuit missionary, Joseph Henri Marie de Prémare, it became the first Chinese play to have been translated into any European language. Voltaire wrote L’Orphelin de la Chine in 1753, adding a love story which was promptly removed by Irish playwright Arthur Murphy in his Orphan of China (1756). Constantly revived on the contemporary stage in China, it was the basis for a 2009 grand opera, Jeffrey Ching’s The Orphan, and a 2010 epic film, Chen Kaige’s Sacrifice.

The central story is so compelling, and the universal themes of Confucian morality, loss, and self-sacrifice are so timeless that The Orphan of Zhao has been translated and amended’”sometimes with radical adjustments to the plot’”for centuries: Adapted into French in 1731 as L’Orphelin de la Maison de Tchao by a Jesuit missionary, Joseph Henri Marie de Prémare, it became the first Chinese play to have been translated into any European language. Voltaire wrote L’Orphelin de la Chine in 1753, adding a love story which was promptly removed by Irish playwright Arthur Murphy in his Orphan of China (1756). Constantly revived on the contemporary stage in China, it was the basis for a 2009 grand opera, Jeffrey Ching’s The Orphan, and a 2010 epic film, Chen Kaige’s Sacrifice.

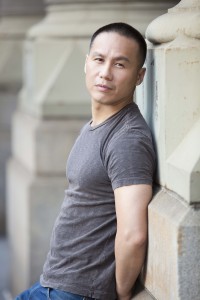

Even so, it remains a drama of which many are unaware. That’s all about to change. One of the most anticipated events of the season, a new version commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company will see its U.S. Premiere in a brand new production by A.C.T. helmed by Carey Perloff. With a sterling ensemble, including Tony Award–winner and San Francisco’s own BD Wong (making his A.C.T. debut), this co-production with La Jolla Playhouse has a limited run June 4-29 at the Geary Theatre, and then July 8-August 3 at La Jolla Playhouse, so he who hesitates to procure tickets is lost.

Even so, it remains a drama of which many are unaware. That’s all about to change. One of the most anticipated events of the season, a new version commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company will see its U.S. Premiere in a brand new production by A.C.T. helmed by Carey Perloff. With a sterling ensemble, including Tony Award–winner and San Francisco’s own BD Wong (making his A.C.T. debut), this co-production with La Jolla Playhouse has a limited run June 4-29 at the Geary Theatre, and then July 8-August 3 at La Jolla Playhouse, so he who hesitates to procure tickets is lost.

In 2011, incoming Royal Shakespeare Company artistic director Gregory Doran approached English poet, journalist, and literary critic James Fenton to write a version for the Stratford-upon-Avon season (Nov. 2012 to Mar. 2013). There it played in tandem with new translations of Brecht’s Galileo and Pushkin’s Boris Godunov under the banner of “the greatest classics you’ve never seen.”

At first, it seemed that critics were poised to annihilate the production, given that RSC employed only 3 East Asian actors out of a cast of 17. The tsunami of praise after opening squelched any opposition. The Guardian: “A stunning act of theatrical reclamation’¦ Often described as the Chinese Hamlet, it reminds me more of the luminous parables of Brecht, who surely borrowed aspects of it in creating The Caucasian Chalk Circle. And, although its story may sound complex, in Fenton’s version it becomes magically clear’¦powerfully moving. What we see is drama hewn out of a myth that speaks across the centuries. It deals with corruption and cruelty, the pain of mothers separated from their children and an unquenchable spirit of goodness.” The Telegraph: “The poet and journalist James Fenton (in his rare and distinguished case that is not an oxymoron) has adapted the play from traditional Chinese sources and tells the complex story with clarity and eloquence. This ancient drama also chimes strongly with the horrors of our own times with its story of cruel dictators and the killing of innocent children’¦Fenton’s text, mostly in prose [but with a few songs] is both subtle and supple.” London Evening Standard: “Fenton’s lucid adaptation draws on multiple sources and is a mix of lyricism and violence.”

At first, it seemed that critics were poised to annihilate the production, given that RSC employed only 3 East Asian actors out of a cast of 17. The tsunami of praise after opening squelched any opposition. The Guardian: “A stunning act of theatrical reclamation’¦ Often described as the Chinese Hamlet, it reminds me more of the luminous parables of Brecht, who surely borrowed aspects of it in creating The Caucasian Chalk Circle. And, although its story may sound complex, in Fenton’s version it becomes magically clear’¦powerfully moving. What we see is drama hewn out of a myth that speaks across the centuries. It deals with corruption and cruelty, the pain of mothers separated from their children and an unquenchable spirit of goodness.” The Telegraph: “The poet and journalist James Fenton (in his rare and distinguished case that is not an oxymoron) has adapted the play from traditional Chinese sources and tells the complex story with clarity and eloquence. This ancient drama also chimes strongly with the horrors of our own times with its story of cruel dictators and the killing of innocent children’¦Fenton’s text, mostly in prose [but with a few songs] is both subtle and supple.” London Evening Standard: “Fenton’s lucid adaptation draws on multiple sources and is a mix of lyricism and violence.”

Says Perloff: “Discovering The Orphan of Zhao was incredibly eye-opening for me, an insight into a vivid moment in Chinese culture and an introduction to a major classic of suspense and sacrifice rarely seen in the Western Theater. We hope our  audiences will be as transported and surprised by this stunning piece of World Theater as we were when we first encountered it.”

audiences will be as transported and surprised by this stunning piece of World Theater as we were when we first encountered it.”

A.C.T. continues its exploration of Chinese culture with a remarkable company of Asian American actors and theater artists, including Byron Au Yong, who is composing the many songs and live musical interludes in the production. Au Yong composes songs of dislocation that mix avant-garde techniques, classical music, and folk ceremonies. See this fascinating clip about Au Yong’s evolution as a composer and his work on A.C.T.’s Stuck Elevator.

I have seen the work of each artist involved with the show; gathering this estimable talent for one production is in itself a stunning achievement. In addition to BD Wong (M. Butterfly on Broadway), the cast includes the distinguished Sab Shimono, who may be locally remembered for performances at A.C.T., but I will forever think of him as Ito in the original cast of Mame (introducing “We Need a Little Christmas”) and Manjiro in the original cast of Sondheim’s Pacific Overtures (introducing “Poems”). Also on the boards are Daisuke Tsuji, a former member of Cirque du Soleil who truly left an impression as a puckish and athletic royal Fool in Oregon Shakespeare’s King Lear; Marie-France Arcilla, who turned repetitive mill work into skilled art in Working at 59E59 in NYC; chameleonic Nick Gabriel’”nerdy in A Midsummer Night’s Dream at SCR, sophisticated in Cal Shakes’ Lady Windermere’s Fan, a master of the comedic pause in A.C.T.’s Once in a Lifetime; Brian Rivera (Cal Shakes’ Hamlet); Paolo Montalban (The Old Globe’s Allegiance, Broadway’s The King and I); Cindy Im (A.C.T.’s 4000 Miles); Philip Estrera (A Christmas Carol at A.C.T.); Orville Mendoza (Peter and the Starcatcher on Broadway); Julyana Soelistyo (Tony Award–nominee for Golden Child on Broadway); and Stan Egi (Golden Child Off-Broadway).

I have seen the work of each artist involved with the show; gathering this estimable talent for one production is in itself a stunning achievement. In addition to BD Wong (M. Butterfly on Broadway), the cast includes the distinguished Sab Shimono, who may be locally remembered for performances at A.C.T., but I will forever think of him as Ito in the original cast of Mame (introducing “We Need a Little Christmas”) and Manjiro in the original cast of Sondheim’s Pacific Overtures (introducing “Poems”). Also on the boards are Daisuke Tsuji, a former member of Cirque du Soleil who truly left an impression as a puckish and athletic royal Fool in Oregon Shakespeare’s King Lear; Marie-France Arcilla, who turned repetitive mill work into skilled art in Working at 59E59 in NYC; chameleonic Nick Gabriel’”nerdy in A Midsummer Night’s Dream at SCR, sophisticated in Cal Shakes’ Lady Windermere’s Fan, a master of the comedic pause in A.C.T.’s Once in a Lifetime; Brian Rivera (Cal Shakes’ Hamlet); Paolo Montalban (The Old Globe’s Allegiance, Broadway’s The King and I); Cindy Im (A.C.T.’s 4000 Miles); Philip Estrera (A Christmas Carol at A.C.T.); Orville Mendoza (Peter and the Starcatcher on Broadway); Julyana Soelistyo (Tony Award–nominee for Golden Child on Broadway); and Stan Egi (Golden Child Off-Broadway).

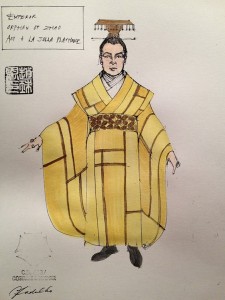

The creative team for The Orphan of Zhao includes scenic designer Daniel Ostling (The White Snake, The Jungle Book, and Metamorphoses for Mary Zimmerman, and Tony-nominated Best Set Design for Clybourne Park); costume designer Linda Cho (2014 Tony Award winner for A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder); lighting designer Lap Chi Chu (Other Desert Cities at the Mark Taper Forum, The Light in the Piazza at SCR); sound designer Jake Rodriguez (Troublemaker at Berkeley Rep); with movement by Stephen Buescher (Head of Movement and Physical Theater at A.C.T.’s M.F.A. Program, he he has been a company member of Dell’Arte International for over a decade).

The creative team for The Orphan of Zhao includes scenic designer Daniel Ostling (The White Snake, The Jungle Book, and Metamorphoses for Mary Zimmerman, and Tony-nominated Best Set Design for Clybourne Park); costume designer Linda Cho (2014 Tony Award winner for A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder); lighting designer Lap Chi Chu (Other Desert Cities at the Mark Taper Forum, The Light in the Piazza at SCR); sound designer Jake Rodriguez (Troublemaker at Berkeley Rep); with movement by Stephen Buescher (Head of Movement and Physical Theater at A.C.T.’s M.F.A. Program, he he has been a company member of Dell’Arte International for over a decade).

A friend of playwright James Fenton, after being told The Orphan of Zhao’s plot, wondered if it was Argentinian. Fenton wrote in The Guardian, “Yes, it has resonances in contemporary Argentina, where children of the ‘disappeared’ have found out that their adoptive parents were responsible for the brutal suppression of the left. But the story has resonances throughout the world: I have often thought of Cambodia; others might think of Uganda, or Rwanda. There is, of course, the  recent history of China itself. One doesn’t need to insert these echoes. They resonate on their own behalf.”

recent history of China itself. One doesn’t need to insert these echoes. They resonate on their own behalf.”

On adapting the work, Fenton continued, “Chinese translations, particularly of poetry, are sometimes completely baffling. Occasionally, our idea of classical Chinese idiom is really just an idea of American modernism; all that tasteful free verse we read in English translation comes from the age of imagism, of Pound and those who were influenced by him. It’s a kind of imaginary China. Chinese poetry itself prefers to rhyme.” While writing Zhao, Fenton devoured The Book of Songs, noting that this’”the earliest poetic anthology of Chinese poetry in the world (c. 600 B.C.)’”is “something we can all appreciate; it gives us a world in which we can fill in the details for ourselves, just as our own border ballads give us a violent, heroic, poetic world. It’s a world of armies on the move, of men pressed into the service of warlords, of chariots on the road.

“I found, to my intense delight, that my simple kind of idiom, with its restricted vocabulary, and its direct style, came alive in unexpected ways. It quickens the pulse. This is the imagined language of a fearsome, distant kingdom. And this, too, is the world of the modern massacre.”

Relevance, exciting and accessible language, an ancient story, and some of the greatest artists working in the theater today easily make The Orphan of Zhao one of the few not-to-be-missed experiences of the year.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

photos courtesy of A.C.T. and the RSC

BD Wong photos by Jim Cox

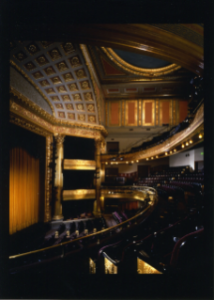

Geary Theatre photo by Marco Lorenzetti

The Orphan of Zhao

American Conservatory Theatre

co-production with La Jolla Playhouse

A.C.T.’s Geary Theater, 415 Geary Street

June 4 – 29, 2014

for tickets, call 415.749.2228 or visit www.act-sf.org

then plays July 8 – August 3, 2014

Mandell Weiss Theatre at La Jolla Playhouse

2910 La Jolla Village Dr, in La Jolla (San Diego)

for tickets, call (858) 550-1010 or visit www.LaJollaPlayhouse.org

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

Greetings. I read your nice preview, and intend to see the production when it heads to La Jolla. Please note that the composer’s last name is a two part surname, “Au Yong,” and not just “Yong.” Certain Chinese names have two syllables, and this is one of them.

Thanks you for letting us know, Eugene – the change has been made!

Went to see the play last evening. It was very well done. It was disappointing that BD Wong did not appear. I wonder why there was no notification in the playbill or a formal announcement.

I found out that a last-minute scheduling conflict came up for BD Wong on Sunday, and the understudy, James Jin Seol, went on in the role of Cheng Ying. Apparently, all went well.