DARK DOINGS IN POSTWAR PARIS

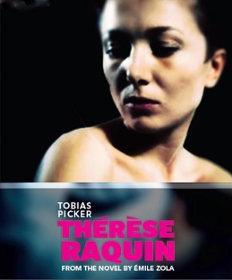

Now in an appropriately driven local premiere by Chicago Opera Theater, Tobias Picker’s two-and-a-half hour opera from 2001 delivers a bleak harvest of shame. The illicit lovers in Emile Zola’s scandalous 1867 novel Thérèse Raquin, based on a true tale of working-class lovers in Paris who murder the woman’s husband and then fall victim to their own guilt, are literally haunted to death. Much like the anguish that haunts Theodore Dreiser’s illicit murderers in An American Tragedy, this is a tabloid-lurid, penny-dreadful potboiler of dead-end passion. Fueled by short-sighted overkill and a ghostly intervention, it’s finally consumed by regret.

Picker’s unrelenting tale, prosecuted by Gene Scheer’s bittersweet libretto, is relocated to the post-war Paris of 1946. The tragic triangle consists of Thérèse, coldly composed, illegitimate daughter of an Algerian woman and a father who discarded her; her first cousin and husband, the sickly mama’s boy Camille; and their childhood friend, ex-soldier Laurent, a sponger who will paint Camille’s portrait but steal his soul and wife. Presiding over this cursed household is Madame Raquin, Thérèse’s controlling aunt and Camille’s ball-breaking mother.

Perhaps if these miserable survivors were blue-blooded royalty, there’d be some dignity to the sordid events. But, pitiless exponent of naturalism at its nastiest, Zola is interested only in conveying “the animal side” of troubled, suicidal lovers twisting on their own knife edge.

Happily, Picker also gives them pathos, the musical equivalent of the glowering clouds that hang above Alan E. Muraoka’s spare and unsparing set. Zola said: “I have simply done on two living bodies the kind of analysis that surgeons do on dead bodies.” Picker is a tad kinder, giving the characters occasional rhapsodic moments as Thérèse remembers her wedding dress or Laurent wonders if God has let the Seine River (scene of the crime) take its own course.

But mostly this corrosively intimate, seven-person story feeds on the frustrations of unlikable characters and spares us no cruelty. (The ugly murder satisfies nothing and sets up its nemesis.) Seen from the start staring into nothingness, Mary Ann Stewart’s title character tautly generates and projects all the emptiness within. She’s set apart by a lonely marriage but equally so by Laurent’s conditional devotion. Edward Parks plays him with an arrogant confidence in stunning contrast to Matthew DiBattista’s forlorn and neurasthenic Camille, a born victim.

Adding to the menagerie are Suzan Hanson’s pointlessly proud Madame Raquin and Zeffin Quinn Hollis as a clueless cop and family friend married to the bubbly and equally ineffectual Suzanne (Ani Maldjian). Finally, there’s the boringly punctual Monsieur Grivet (John Matthew Myers), a dinner-loving doctor who’s oblivious to the symptoms of heartbreak all around him. Veteran director Ken Cazan and conductor Andrea Mitisek fully honor a supple score and the crime it refuses to condemn completely.

The production was rightly dedicated to Andrew Patner, a brilliant arts writer and opera enthusiast who died last month, too early, at 55. It added to a bitter work’s uncompromising despair, the thought that this esteemed colleague wasn’t here to help make it matter.

photos courtesy of Chicago Opera Theater

Thérèse Raquin

Chicago Opera Theater

Harris Theater, 205 E. Randolph

ends on February 28, 2015

for tickets, call 312.704.8414 or visit www.chicagooperatheater.org

for info on Chicago Theater, visit www.TheatreinChicago.com