CONDITIONAL LOVE AND EARLY DEATH

The perils of parenting are center stage in Steppenwolf Theatre Company’s truth-teller. British playwright Rory Kinnear’s strangely named The Herd (a title that could indict the characters or the audience) exposes a curse as searing as any the House of Atreus endured. It measures a suburban London family beyond all clichés about what love can fix. At the play’s core lies a cunning contradiction: How much can you love a damaged child before wanting him to die–for his good as much as yours?

Frank Galati’s pile-driving staging, a U.S. premiere, assembles a capital cast to push the limits of a penetrating play. Three generations are gathered to wryly celebrate a milestone that’s a feat of survival: It’s the 21st birthday of Andy, a severely disabled young man who was never supposed to see 19. The affliction’s cause is deliberately unspecified, though it’s something as consistently cruel as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy or multiple sclerosis. In any case Kinnear’s loved (or unloved) ones define themselves by how they handle an adult with the mind of a 10-month baby.

Having sacrificed time and people for her son’s sake, Molly Regan’s Carol is a tiger-tenacious wonder of tough love, micro-managing every aspect of Andy’s changing challenges. Right now he and his obnoxious caregiver Jackie have not come back from a doctor’s appointment. But Andy’s absence is itself a presence. Arriving with presents and advice are his stolid grandparents Brian (John Mahoney) and Patricia (Lois Smith). These two actors, who have run more gamuts and gathered more kudos than entire troupes, bring vibrant humor but not survivor wisdom to their untested first generation (they could only be passive protectors to Andy).

The third generation is represented by Andy’s 33-year-old sister Claire (Audrey Francis), a sibling with a very real rival. She’s brought along her boyfriend Mark (Cliff Chamberlain), a performance poet and carpenter, to audition for the family at a crucial get-together. As it turns out, Claire’s concern for hers and Mark’s futures, as much as Andy’s, is no abstraction. Her fears, however, may well be so.

Finally, uninvited and toxically unwelcome is Andy’s father Ian (Francis Guinan), a well-targeted traitor who hasn’t seen his son in five years. He’s remarried and sired a healthy child since abandoning his marriage of 20 years and, most inexcusably, Andy. His arrival triggers abuse so terrible you end up pitying a cowardly father for  whose sins there seems no statute of limitations. His simple wish to see his son is no atonement–but it’s hardly as evil as utter indifference. Trapped in a classic no-win situation, Ian feels forced to prove a negative–his love for his son–without the slightest benefit of the doubt. But love, a habit hard to hide, will, as we see, find a way.

whose sins there seems no statute of limitations. His simple wish to see his son is no atonement–but it’s hardly as evil as utter indifference. Trapped in a classic no-win situation, Ian feels forced to prove a negative–his love for his son–without the slightest benefit of the doubt. But love, a habit hard to hide, will, as we see, find a way.

Despite the unsettling context of what should be a managed family reunion, Kinnear delivers an authentically recognizable family function. The conversation mostly hews to the conventionally commonplace–curiosity about Claire’s beau, Brian’s experience as the only man in a Shakespeare appreciation class, Mark’s on-the-spot improvising. But underneath the small talk you see scar tissue, badly buried pain that laughter can’t cure. The wisest consolation for them all is the grandfather’s unheard recitation of Portia’s “quality of mercy” speech. Forgiveness is earned precisely because it’s not deserved.

Setting aside the recriminations, guilt-giving and blame-throwing, the play is haunted by what’s finally addressed–whether Carol’s all-consuming caretaking and almost predatory possessiveness can balance or outweigh Andy’s unfinished incapacities. Surely the lad’s purpose on the planet wasn’t to gauge his family’s fortitude. If that’s all there was, would he be better off dead?

Galati’s inspired sextet chronicle every nuance of a fractured family–the similarly handicapped Brian’s cheerful pluck, Patricia’s deadpan dismissals of cant and lies, Mark’s simple-hearted (but not simple-minded) devotion to an understandably anguished Claire, and Ian’s unflinching abnegation as a failed father who still should breathe. Above all, there’s Carol’s strangely soul-shrinking self-sacrifice.

The one incongruity in this pitch-perfect production is Walt Spangler’s oddly sumptuous set, its awesome luxury unexplained by the script. You’d think a single mother caring for a very sick child would not live in gorgeous digs with huge, Blake-like canvases seemingly borrowed from the Tate Gallery. There’s enough to feel in The Herd without giving us so much gaud to envy.

photos by Michael Brosilow

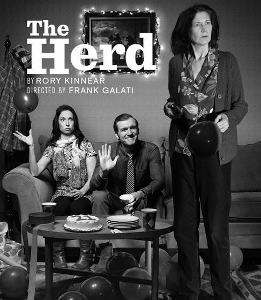

poster photo by Saverio Truglia

The Herd

Steppenwolf Theatre Company

1650 N Halsted St

ends on June 7, 2015 EXTENDED to June 14, 2015

for tickets, call 312.335.1650 or visit www.steppenwolf.org

for more info on Chicago Theater, visit www.TheatreinChicago.com