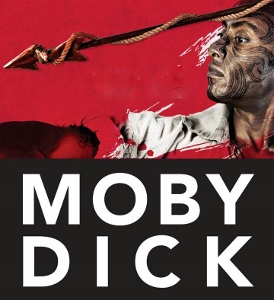

A LEVIATHAN BEACHES ON MICHIGAN AVENUE

Moby Dick, Herman Melville’s whale of a tale (or tale of a whale) from 1851, is as unsinkable as its title cetacean. It’s never been more so than in Lookingglass Theatre Company’s summer sensation staged and adapted by David Catlin. In little less than three hours the enthralling panoply of a sprawling novel–the lore of the sea, elemental clash of species and egos, the sheer horrors of untamed hubris–explodes beneath their concentrated proscenium. Courtney O’Neill’s supple set–concentric whalebone ribs that double as masts, a full rigging fit for a whaleship, and a deck that looks like it was carved from burnished petrified wood–becomes, well, whatever. We’re in a New Bedford inn where sole survivor Ishmael and cannibal prince Queequeg “bundle,” the sailors’ church where Jonah is invoked as warning and avatar, the bustling Nantucket Island harbor, and, of course, the Pequod. On this ship of fools peg-legged Captain Ahab mounts an implacable revenge against the huge albino sperm whale that took his leg and, like the crocodile in Peter Pan, presumably wants the rest.

Moby Dick, Herman Melville’s whale of a tale (or tale of a whale) from 1851, is as unsinkable as its title cetacean. It’s never been more so than in Lookingglass Theatre Company’s summer sensation staged and adapted by David Catlin. In little less than three hours the enthralling panoply of a sprawling novel–the lore of the sea, elemental clash of species and egos, the sheer horrors of untamed hubris–explodes beneath their concentrated proscenium. Courtney O’Neill’s supple set–concentric whalebone ribs that double as masts, a full rigging fit for a whaleship, and a deck that looks like it was carved from burnished petrified wood–becomes, well, whatever. We’re in a New Bedford inn where sole survivor Ishmael and cannibal prince Queequeg “bundle,” the sailors’ church where Jonah is invoked as warning and avatar, the bustling Nantucket Island harbor, and, of course, the Pequod. On this ship of fools peg-legged Captain Ahab mounts an implacable revenge against the huge albino sperm whale that took his leg and, like the crocodile in Peter Pan, presumably wants the rest.

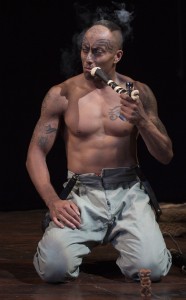

Lookingglass Theatre (here associated with their Actors Gymnasium) never met a story they couldn’t illustrate–and how they rise to this occasion! Caitlin preserves both the sweep and warmth of Melville’s cautionary novel. He feelingly depicts the 32-strong band of brothers embarked on a transoceanic hunting expedition that turns into almost total defeat by one branch of mammals over another. There’s a very odd couple–a Biblical-like witness/narrator–call him Ishmael! (Jamie Abelson)–and his spear-carrying South Sea soulmate Queequeg (Anthony Fleming III). The rest of the crew are stalwart, sensible Stubb (Raymond Fox), fiery first mate Starbuck (Kareem Bandealy) who, protecting the owners’ interests, defies Ahab’s death-wish vendetta, haunted Cabaco (Micah Figueroa) whose near drowning unhinges him, and Mungun (Javen Ulambayer), a “prince of whales” able to render a monster carcass from blubber to whale oil, ambergris, and future corsets.

Lookingglass Theatre (here associated with their Actors Gymnasium) never met a story they couldn’t illustrate–and how they rise to this occasion! Caitlin preserves both the sweep and warmth of Melville’s cautionary novel. He feelingly depicts the 32-strong band of brothers embarked on a transoceanic hunting expedition that turns into almost total defeat by one branch of mammals over another. There’s a very odd couple–a Biblical-like witness/narrator–call him Ishmael! (Jamie Abelson)–and his spear-carrying South Sea soulmate Queequeg (Anthony Fleming III). The rest of the crew are stalwart, sensible Stubb (Raymond Fox), fiery first mate Starbuck (Kareem Bandealy) who, protecting the owners’ interests, defies Ahab’s death-wish vendetta, haunted Cabaco (Micah Figueroa) whose near drowning unhinges him, and Mungun (Javen Ulambayer), a “prince of whales” able to render a monster carcass from blubber to whale oil, ambergris, and future corsets.

Equally busy are the able-bodied actresses (Emma Cadd, Monica West and Kasey Foster) who play a crone, a widow, an innkeeper, and, finally (and a bit unconvincingly) Moby Dick—three Furies devouring the doomed. Awesomely athletic and mimetic to beat the Greeks, Catlin’s nine actors sail full speed ahead into an unstoppable epic. The fluid casting is echoed in the props: In this metamorphosing world anything can change purpose: Queequeg’s intricately carved coffin becomes Ishmael’s sudden lifeboat and a whale’s ribcage doubles as a ship’s skeleton.

At the vortex of this voyage, of course, is Christopher Donahue’s driven, self-destructive Ahab, consumed by suicidal hatred of a dumb creature to whom he credits supernatural malevolence and personal spite. Pursuing the great white whale with a scarred fluke, Ahab, both “god-like” and “ungodly,” abandons one species to destroy another. He risks the ire of Massachusetts merchants by putting vengeance over profits, neglecting the whale oil barrels that leak in the hold. His worst transgression is to reject Captain Gardiner’s heartbreaking plea to find his lost 12-year-old son. Breaking faith with humanity dooms Ahab’s ship as much as any typhoon or stowed-in-keel. The doubloon that he promises to whoever sights his nemesis becomes fool’s gold and goes down with the ship.

No Currier and Ives-like, period-perfect presentation, Catlin’s picture-laden staging happily leaves both little and much to the imagination. It employs suggestion as much as substance to conjure entire seascapes and a teeming deck. Swathes of silk become ocean billows, whale oil lamps are lit and hung above like stars, a harpoon is welded in a fiery forge, a tempest shakes the stage to the topmost mast, and, in a borrowing from Blue Man, the audience is briefly covered by a huge white wave. With Mary Zimmerman-like miniaturization, model ships stand for real ones and a baby whale becomes heartbreaking as it dies with its mother, the placenta still attached. Suspended sledges stand for swinging hammocks or careening whaleboats (what they called a “Nantucket sleigh ride”). Almost everything’s shown but scrimshaw carving and the ghostly green phosphorescence of St. Elmo’s Fire that covers the ship like a curse.

It’s monumental picturebook storytelling, even at the risk of skirting the whirlpools of melodrama. These sails never droop in a narrative calm. It’s battened down and ship shape as the author imagined. One cavil is the unavoidable disappointment of not seeing the 1956 film’s Moby Dick with Gregory Peck’s dead flailing arm harnessed by hemp to a vast killer whale. The other is missing Melville’s meditation on “the whiteness of the whale.” (He eloquently argues that white, not black, is the hue of evil–as in sharks, polar bears, blizzards and, of course, a very angry leviathan.) But the rest is wonder on spectacle. “There she blows!” indeed.

photos by Liz Lauren

Moby Dick

Moby Dick

Lookingglass Theatre Company

in association with The Actors Gymnasium

Water Tower Water Works, 821 N. Michigan Ave.

ends on August 9 EXTENDED to August 28, 2015

for tickets, call (312) 337-0665

or visit www.lookingglasstheatre.org

for info on more Chicago Theater,

visit www.TheatreinChicago.com