THE OLD TESTAMENT MEETS THE NEW WORLD

A saga of American origins, John Steinbeck’s most ambitious novel was published in 1952 and, three years later, starred James Dean and Julie Harris in a seminal film version. Archly aphoristic, portentous with easy wisdom, East of Eden is a solemn and serious California update of the Biblical legend of feuding brothers Cain and Abel, the former a murderous hunter, the other a gentle farmer. Both were dangerously eager to sacrifice for their noble father Adam and to avoid the fate of evil mother Lilith. Both elemental and dated, melodramatic, cinematic and novelistic, this sprawling spectacle recalls Eugene O’Neill’s New England retellings of Greek tragedies in American parlors. It teems with timeless issues–cross-generation contamination, endangered honor, free will and original sin, and lies and loyalty.

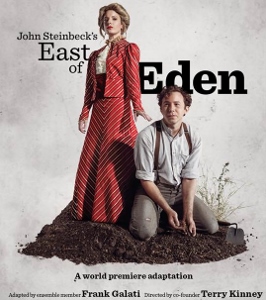

Now cometh Steppenwolf Theatre’s three-hour stage version by company member (and two-time Tony-winner) Frank Galati. Monumentally helmed by theater co-founder Terry Kinney, it’s a grand parable of disobedience and reconciliation. Set in the breadbasket Salinas valley between 1900 and 1918, the dialogue veers from shockingly direct to baroquely sententious, sometimes within the same speech. But, marinating in insistent significance, the oracular action often rises to Old Testament occasions. If America is its own “genesis,” we’re present at a suitably epic creation. The birth of sin in an agricultural Eden triggers a family dysfunction and sibling rivalry that feel as familiar as they’re archetypal.

The primal protagonist is Tim Hopper’s haunted Adam Trask, a California dreamer hoping to dig wells and found a peaceful empire in his gentle garden of an inland valley. But the primary antagonist is Cathy (an implacable Kate Arrington), his preternaturally and unaccountably wicked wife. This faithless blackmailer bears her own “mark of Cain.” She wants no role in or part of this beautiful estate. After screamingly delivering twin boys, she shoots her way out of the birthing bedroom and stalks off to become the unscrupulous madame of a gilded whorehouse.

Seeking warmth and serenity to make up for this desertion, Adam delights in siring sons (or are they indeed his?). In any case he must hide a truth that will set no one free. He tells the lads that mom is not just gone, but dead. Alas, this perverse ignorance is the opposite of innocence.

Adam remains bovinely content to grow stuff and to invest, losingly, in an ice machine to refrigerate perishable products b0und for Eastern markets. A kind of Greek-Asian chorus, Stephen Park plays a Chinese caretaker whose pronouncements are, yes, maddeningly and stereotypically inscrutable. Over the next two decades the boys–blond and benevolent Aron (Casey Thomas Brown), who resembles his mother in all but wickedness and restless, scheming and entrepreneurial Caleb (Aaron Himelstein)–wonder about their lost parent.

Seeking a very different woman in their lives, the brothers are drawn to small-town ingénue Abra (Brittany Uomoleale). Averse to Aron’s reflexive goodness, Abra finds Caleb’s searching more agreeable than Aron’s moral certitude: A kind of serpent in this false paradise (he prefers profitable beans to losers’ lettuce), Caleb rejects his father’s contented cultivation. When he reunites with his supposedly dead mother, it sets in motion unintended consequences, including a loved one’s suicidal escape to the trenches of World War I. Can an act of deathbed forgiveness from a stricken father atone for Caleb’s toxic truth-telling?

It’s all played under set designer Walt Spangler’s gigantic tree of knowledge, a California oak that must hold giants in its unseen branches. What we see below the tree is a mixed blessing: In drama little things take up much more room than they do in a novel; at times this East of Eden fritters away its focus.

There’s also a stylized grandeur to these proceedings that lends itself to unearned emotions. The grandiose tone sometimes conflicts with the script’s equally laid-back landscape, matter-of-fact exchanges, and “lettucehead” lifestyle. (To its credit The Grapes of Wrath–a 1988 Steppenwolf triumph–was too rooted, or rootless, in Depression dust to signify more than stark survival.) But, buttressed by an original score by Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen, the sheer sweep of Steppenwolf’s quirky, sometimes arbitrary, storytelling, is a marvel unto itself. Americans in the early 20th century, it seems, were not too small to enact their own Bible. Maybe we deserve Steinbeck’s outsized transgressions.

East of Eden

Steppenwolf Theatre Company

1650 N Halsted St

ends on November 15, 2015

for tickets, call 312.335.1650 or visit Steppenwolf.org

for info on more Chicago Theater,

visit TheatreinChicago.com