ALMOST TRUSTWORTHY

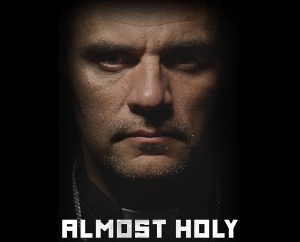

The collapse of the Soviet Union led to, among other things, an epidemic of child homelessness in its former republics. Whether orphaned, escaping impossible domestic situations or poorly run government institutions, on the streets these children become junkies, prostitutes, criminals. They are used and abused, raped, beaten and murdered. Officials’”assuming they are not so corrupt that they directly benefit from the victimization of such children’”lack both the resources and the inclination to deal meaningfully with this overwhelming problem. Such is the case throughout the former USSR; such is the case in Mariupol, Ukraine, where charismatic “vigilante” pastor Gennadiy Mokhnenko has taken it upon himself to rescue these children from their predicaments, whether they like it or not. Steve Hoover’s Almost Holy attempts to document the pastor’s activities.

Towards the beginning of the film we watch Mr. Mokhnenko, an imposing, athletic man, and his crew, which consists mostly of rescued children, ride around in a van at night looking for homeless kids to save. They find an adolescent girl, her face horribly swollen from a savage beating, and force her into the van despite her violent reluctance. We see Mr. Mokhnenko lift boys out of a manhole where they had settled in for the night with a middle-aged man who was apparently paying them for oral sex; the man is arrested. Later there is heart wrenching footage of children younger than ten with horrific track marks all over their bodies. The sequences are effective and tell a tragic and fascinating story.

Like many viewers jaded by tales of seemingly well-intentioned individuals who turn out to be predators or Nazis or suicide cult leaders, I went into Almost Holy with a wait-and-see attitude. But Mr. Mokhnenko appears to be the genuine article, a truly remarkable man, indeed almost holy. He and his wife, who have children of their own, have adopted a number of the kids he’s taken off the streets. His Pilgrim Republic rehabilitation center looks like a bright and civilized place where youngsters are provided with all the essentials. And although many of the residents are brought there against their will they are not forced to stay. By the twenty minute mark I was so moved by the efforts of this amazing individual that fanciful notions of moving to Mariupol and helping out started flitting about in my mind.

Unfortunately, it is around this time that Mr. Hoover’s film begins its nosedive. The sense one gets is that instead of spending a year or two shadowing his subject, Mr. Hoover devoted a couple or few months to the activity. Storylines aren’t as distinct as they should be and don’t evolve in dramatically satisfying ways. There is also a good deal of padding, with material that is too often questionable: Scenes that are meant to be authentic are clearly staged. We get an extended sequence of Mr. Mokhnenko hitting the heavy bag, of kids working out, all of it choreographed’”clumsy and frustrating attempts at metaphor. Mr. Hoover inserts footage of his subject on Ukrainian talk shows defending his methods. If the government can’t deal with this problem then I’m going to take matters into my own hands, Mr. Mokhnenko says in substance, at which point the crowd bursts into applause. The director uses this approbation as evidence of the righteousness of Mr. Mokhnenko’s actions. Yet one could easily imagine this same crowd of poor, powerless, suffering Ukrainians applauding a Mussolini-type character offering simple but brutal solutions to complex problems.

But most problematic is Mr. Hoover’s puzzling decision to casually include generous portions of Western news reports about Russia’s takeover of Crimea and her alleged involvement in Ukraine’s separatist movement. Is he saying that Russia’s behavior is responsible for child homelessness in the former republic? It’s not certain. But what is certain is Mr. Hoover’s unequivocal condemnation of the superpower’s actions, a judgment he gives us no choice but to agree with, without providing any evidence or arguments in its favor. At this point it’s difficult to take anything Mr. Hoover says seriously. We sense that there is a falseness to what he’s telling us. And whether he’s naïve or incompetent or promoting an agenda doesn’t matter, his benign intentions don’t matter. What matters is that we don’t trust him. And the one thing a documentarian cannot afford to lose is our trust.

photos © The Orchard

Almost Holy

The Orchard and Animal presentation

in Russian and English | 2015 | Color | 100 min.

open in New York and Los Angeles on May 20, 2016

followed by limited release

for more info and dates, visit Almost Holy