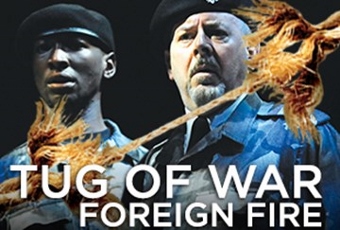

BINGEWATCHING THE BARD

“Tug of war”–a child’s game that mutates into an adult’s nightmare; it’s an apt title for Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s marathon of Bard history plays. Tug of War: Foreign Fire revisits the lowlights from the Hundred Years War between England and France. We see’”and feel–strife from both sides and at all levels, a harrowing chronicle of self-destructive ambition and utter waste. (Further celebrating Shakespeare at 400, this fall the equally long sequel Tug of War: Civil Strife will combine Henry VI, Parts 2 and 3 and Richard III, reprising the fratricidal and internecine War of the Roses and completing a cycle of victory bequeathing defeat.)

Eclectic with jarring elements, dramatically delivering parallels between successes and surrenders, and democratic in its equal emphasis on mighty lords and obscure soldiers, adaptor/director Barbara Gaines’ magnum opus is poetry at full throttle. Leveling the battle (and the playing) fields, it offers in six hours a sprawling look at clashing dynasties and power politics. Here the means eclipse the ends: Tug of War feels as true to the 21st as to the 15th century.

It’s also a stunning showcase for 19 of Chicago’s keenest actors, playing over 100 parts and conferring an intimacy on history that refreshes and astonishes alike. At times intrusively interrupting and defying the production’s pseudo-medieval look, live rock music injects everything from blues to Bach, Pete Townshend to Tim Buckley, even the lament “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” into the action. (You might call these musical flashforwards the Attack of the Anachronisms.)

To streamline her combat-ready compilation, Gaines distills the most bellicose scenes from the little known Edward III (thought to be partly written by Shakespeare). This uneven work details both a Scottish insurrection and England’s peak of conquest at the battle of Plessy. (Edward was the last king before the Tudor advent to transcend the squabble between the houses of York and Lancaster.) Chronologically skipping both parts of Henry IV (no comic relief like Falstaff permitted here!), we watch a grownup Prince Hal inflict more regime change: A patriotic pageant, Henry V delivers another costly British triumph at Agincourt. The first part of Shakespeare’s earliest history saga Henry VI portrays the losses of a weak king as well as the spiritual and suicidal sacrifice of Joan of Arc, the maid of Orleans who rallies her French against an Iraq-like invasion.

A literal tug of war is symbolized from the start by a handful of kings scrambling for a giant, elusive golden tire that symbolizes throne, crown and more. (A curious icon for a pre-rubber era, it’s one of many tires scattered across the stage. Goodyear should sponsor this spectacle.) Scott Davis’s set, cinematic proscenium-topping scaffolding flanking a wooden runway, is ground zero for dueling kingdoms and fated mortals.

In the first part, Freddie Stevenson’s gaunt, magisterial Edward III wages all against Kevin Gudahl’s French nemesis. There’s a strange extramarital courtship where the Plantagenet winner employs blackmail to woo the unwilling Countess of Salisbury (Karen Aldridge, dignified and demure).

Next, Edward’s great grandson Henry V (John Tufts, suitably valiant) engages in chillingly similar threats and aggression against Larry Yando’s epicene and haunted Charles VI. Here the subplot (confusing out of context) involves an ethnic quarrel among four splenetic captains. We also savor the priceless scene where the king mingles incognito with soldiers who must die for him the next day: Warmly human, Shakespeare’s meeting of monarch and minions is a seminal moment in the history plays where individual conscience gets weighed against abstractions like honor and duty. This “little touch of Harry in the night” is flawlessly felt and deeply engaging.

The final’”and weakest–king in C.S.T.’s first installment is Steven Sutcliffe’s too-trusting and overly cerebral Henry VI. This bookish ruler proves a pawn to everyone around him, especially David Darlow’s scheming bishop and James Newcomb and Alex Weisman’s intrepid Talbot father and son. Equaling their ardor, Heidi Kettenring as Joan la Pucelle invents guerrilla warfare: The armor-clad avenger lifts a siege and crowns a king (Freddie Stevenson, who all but beds the future saint). Gaines’s massive enterprise ends inconclusively in a perfunctory finale: A dithering Henry is about to marry the Earl of Suffolk’s mistress (Aldridge as the simple-hearted Margaret of Anjou). In effect we come full circle from Aldridge’s Countess to her final marital chesspiece.

When three stuffed scripts are reduced to six rushed hours, it’s no surprise that as much is as struck from the sources as is left out of this synopsis. Sweeping change, artistic or actual, always runs the risk of audience exhaustion and (literal) theatrical overkill (though the stage fights here are more stylized than graphic). But, by process of elimination, Gaines’s excisions reinforce what remains’”a kinetic exposé of the unintended consequences when humans kill humans.

When three stuffed scripts are reduced to six rushed hours, it’s no surprise that as much is as struck from the sources as is left out of this synopsis. Sweeping change, artistic or actual, always runs the risk of audience exhaustion and (literal) theatrical overkill (though the stage fights here are more stylized than graphic). But, by process of elimination, Gaines’s excisions reinforce what remains’”a kinetic exposé of the unintended consequences when humans kill humans.

In any case much fine work’”Barbara Robertson’s dynamic courtiers, Neil Friedman as a gruff Scottish chieftain, Michael Aaron Lindner’s fiery Welsh patriot’”makes what might have been a long haul into a tight and tragic tableau worthy of Tolstoy. Though arguably less than the sum of its parts, the sheer scope of Tug of War is equaled by its dramatic depth. Gaines’s fusion of the political and the personal powers Shakespeare’s plays and reignites a crowd’s imaginations. You feel many tugs in this game of thrones.

photos by Liz Lauren

Tug of War: Foreign Fire

Chicago Shakespeare Theater

Courtyard Theater on Navy Pier

ends on June 12, 2016

for tickets, call 312.595.5600 or visit Chicago Shakes

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago