COLORFUL CHARACTERS AIN’T ENOUGH

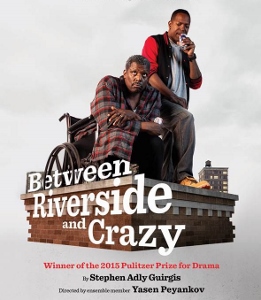

Between Riverside and Crazy is a 2015 slice of strife from Stephen Adley Guirgis (perpetrator of The Motherf**ker with the Hat and Jesus Hopped The ’˜A’ Train). It’s a very N.Y.C. story of unprocessed rage and self-sustaining disappointment. Character-driven by hard luck Big Apple survivors ever on the edge (of breakdowns, breakups, breakouts), it hasn’t got a plot to piss in. If Steppenwolf Theatre wanted to prove it’s an actors’ theater more than an audience’s, this Chicago premiere, tossed and turned by director Yasen Peyankov, makes a bad argument all too well.

In this Pulitzer winner (it was a weak year), Guirgis in effect hands us seven works in regress, then asks us to make sense of Gothamites who don’t mean or do what they say or feel.

At the vortex is Pops (Eamonn Walker, “Chief Boden” on NBC’s Chicago Fire), an ex-cop living in a rent-controlled dump on Riverside Drive. (It’s wonderfully cluttered by designer Colette Pollard, featuring an unexplained but functioning Christmas tree in summertime and a sprawling rooftop.) A sullen grumbler slumping in his dead wife’s wheelchair, Pops (aka Walter Washington) remains bitter over how much citizens hate cops for what they (the police and the public) do or don’t do. Worse, they loathe black cops even more. And he doesn’t like his dog.

Walter is particularly and permanently enraged over an unpardonable act of disrespect: For the last eight years he’s sued the city over an incident he can’t forgive: Pops was shot six times, while out of uniform and drunk as sin in an off-limits dive at 6 a.m., by a rookie white cop who allegedly used the N-word. Due to suspicious circumstances, his suit never had much merit. Now the city is pressuring him to settle by threatening to kick him out of his $1500-a-month digs and cutting off benefits. Pops couldn’t care more.

Meanwhile, his rent-stabilized flat has become a notorious half-way house: A weird meeting place for cops and cons, it harbors Guirgis’s patented brand of half-baked denizens. Walter’s son Junior (ensemble member James Vincent Meredith) is an ex-con in skittish love with pregnant goodtime girl Lulu (Elena Marisa Flores). Their passion is the play’s one non-negotiable bedrock certainty. It’s not enough.

Meanwhile, his rent-stabilized flat has become a notorious half-way house: A weird meeting place for cops and cons, it harbors Guirgis’s patented brand of half-baked denizens. Walter’s son Junior (ensemble member James Vincent Meredith) is an ex-con in skittish love with pregnant goodtime girl Lulu (Elena Marisa Flores). Their passion is the play’s one non-negotiable bedrock certainty. It’s not enough.

Exploiting Pops’ clueless hospitality, Guirgis’ con-artist crazies include ex-offender Oswaldo (Victor Almanzar), a “son” to Pops (he’s got major issues with his real dad). Unhappy toiling at community service, Oswaldo is torn apart by his own “emotionalisms.” He’s also an addict selling stolen goods, his way of showing gratitude for the shelter he’s got. Visiting Pops on a mission from God knows where is Church Lady (Lily Mojekwu), a Brazilian voodoo princess with designs on Pops. Ministering to his privates, she tries to restore this supposedly paralyzed invalid to life if not love.

Finally come the cops among the cons. Now living on Long Island, detective Audrey O’Connor (Audrey Francis), Pops’ former partner, is enraptured with poker whiz Lieutenant Cara (ensemble member Tim Hopper). Perversely, they’re here to remind Pops that he lost his badge and to pressure him into ending the litigation that could lose him his uptown home. Always ripe to take offense, Pops rejects Audrey’s threats and resents Cara’s on-the-make opportunism.

In essence Guirgis assembles seven live wires, makes them bluster and fester, then doesn’t know where to take them. More a rogue gallery of scammers and deadbeats than an organic whole, these urban stereotypes manifest themselves in quirks and quarrels and cease to exist when they’re silent (which is seldom). Like the storyline, they make themselves up as they go along. Our paltry payoff is to watch seven not so lovable losers undermine each other and themselves–textbook cases of off-mission fanatics, false believers who redouble their energy as they forget (or forfeit) their cause.

The play’s ending is especially unsatisfying, not because there was much to resolve but because it’s unearned, as arbitrary as the peccadillos that precede it. If a house built on sand cannot stand, a play made of mendacity can’t convince. Kinder theatergoers will call Guirgis’s artful deceptions so many character contradictions. But it still feels like a clusterfuck of “emotionalisms” (a great term for how it all falls short).

But Between Riverside and Crazy can entertain: Steppenwolf doesn’t drop that ball. The two hours aren’t dull, if only because our distrust of these shifty schemers turns into a tantalizing test of tolerance. Occasionally we glimpse the neediness and hunger behind their poker-bluffing hustles and scrounging for tomorrow. Then the “crazy” in the title becomes more than a formula for funny. But at best it’s a cry for help from folks who can’t come clean.

photos by Michael Brosilow

photos by Michael Brosilow

poster photo by Saverio Truglia

Between Riverside and Crazy

Steppenwolf Theatre Company

Downstairs Theater, 1650 N Halsted St

ends on August 21, 2016

for tickets, call 312.335.1650 or visit Steppenwolf

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago