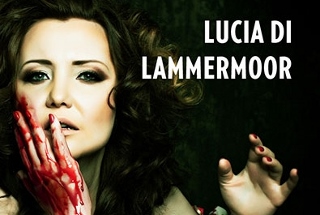

PLEASE, SIR, I WANT SOME LAMMERMOOR

Perhaps this season’s opening production of Wagner’s Das Rheingold raised the bar too high. Lyric’s follow-up effort doesn’t quite reach those celestial heights. And this comes from someone who much prefers Donizetti’s bel canto score. Indeed, this Lucia di Lammermoor is eminently enjoyable to listen to, boasting excellent performances from Russian soprano Albina Shagimuratova and Polish tenor Piotr BeczaÅ‚a, but Graham Vick’s direction is visually unsatisfying.

Based on Sir Walter Scott’s popular novel The Bride of Lammermoor (1819), librettist Salvadore Cammarano’s Lucia is a compact tale of romance and tragedy set in the Scottish Highlands. Act I introduces the audience to the forbidden love of Sir Edgardo of Ravenswood and Lucia Ashton, whose brother Lord Enrico Ashton has promised her hand to Lord Arturo Bucklaw. After Enrico tricks Lucia into believing that Edgardo has not remained faithful to her, she reluctantly marries her suitor in Act II. When Edgardo returns from war in France in the middle of the wedding and sees her signature on the contract, he curses Lucia. Act III shows us a Lucia who has already gone mad and killed her husband. As Edgardo arrives for his duel with Enrico, he discovers that Lucia is dead and promptly kills himself in order to join her in the afterlife.

Despite the Romanticism of the story, Mr. Vick explicitly strives for a more Classical approach befitting Lammermoor‘s 18th–century setting, one that sees “emotions through the prism of the third eye.” Unfortunately, Vick and designer Paul Brown do this all too literally by framing our view of the action with painted panels that move to the center from the top and bottom, right and left of the stage like the shutters of a camera lens.

Despite the Romanticism of the story, Mr. Vick explicitly strives for a more Classical approach befitting Lammermoor‘s 18th–century setting, one that sees “emotions through the prism of the third eye.” Unfortunately, Vick and designer Paul Brown do this all too literally by framing our view of the action with painted panels that move to the center from the top and bottom, right and left of the stage like the shutters of a camera lens.

These frames seem designed to simulate fog in the first act, but they have more symbolic uses later. As Enrico persuades Lucia to accept Arturo in marriage, the horizontal panels slowly shift from right to left, the weather-beaten tree in the background where Edgardo and Lucia pledged their love gradually giving way to a tall, proud tree that seems to symbolize her suitor. As Raimondo tells of Lucia’s madness in the final act, the horizontal panels dramatically part to reveal the blood-soaked bride descending from her high tower. Only during the final scene do all of these frames completely recede.

Another peculiarity is the ever-present moon sailing across the night sky, setting the action in a perpetual night that is relieved, as with the frames, only in the final scene. This has the unhappy effect of making the opera far gloomier than it need be. In fact, Donizetti’s often boisterous score feels as if it is trying to break free of Vick’s dark and confining set. One should add that the movements of set and perspective, while inarguably creative, are no substitute for the lack of movement of the production’s mostly sedentary cast.

Shagimuratova ably fulfills Lucia’s titular role with confidence born of experience and a dramatic power that comes close to overwhelming the nimble coloratura of her character’s famous “mad scene.” Not a single note of the opera, however, quite compares with the transcendent high F that she sings following her relatively unadorned cadenzas. It’s a breathtaking moment. Also remarkable is BeczaÅ‚a’s turn, whose noble voice and valiant expression suffuse the role of Edgardo with an abundant measure of heroism. Quinn Kelsey, although clearly an audience favorite as Enrico, lacks the polish and grace that would propel him beyond the antagonistic roles he seems to gravitate towards. (At Lyric, he was last seen playing the grasping Count di Luna in Verdi’s Il Trovatore.) Romanian bass Adrian Sâmpetrean makes an impressive Lyric debut as the clergyman Raimondo Bidebent, a role that could have easily been overshadowed if filled by someone with less gravitas.

Despite Vick’s idiosyncratic direction, Lucia di Lammermoor remains an enjoyable production. In addition to some first-rate soloists, there is the inimitable Lyric Opera Chorus under the direction of Michael Black, whose vibrancy counterbalances Scott’s woeful tale. And the primary colors of Brown’s attractive period costumes have just enough tartan to evoke its Scottish setting. But Lucia could have been rather better.

photos by Todd Rosenberg and Andrew Cioffi

Lucia Di Lammermoor

Lyric Opera of Chicago

Civic Opera House, 20 N. Wacker Drive

ends on November 6, 2016

for tickets, call 312.827.5600 or visit Lyric Opera

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago