VICTORY AND DEFEATISTS

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

[Editor’s Note: Oeuvre Total is a film-discussion series. The first exchange concerns Billy Wilder, and our contributors are producer Michael Holland and critic Jason Rohrer. Stage and Cinema republished the original seven entries begun at Bitter Lemons and offer this, Mr. Holland’s brand new post, as a follow-up to Part VIII by Mr. Rohrer.]

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

It’s the holidays here in Los Angeles. Perhaps that sounds odd because, of course, it’s the holidays all over the world; Christmas days ago, we’re in the middle of Chanukah and Kwanzaa, with The New Year days away. And here in L.A. — truly more of a melting pot than an outsider might believe — they all wonderfully mean something. A little of this, a little of that, a lot of it all, depending on how much you let in. I mention it because, for us Angelinos, it’s something of a rare holiday spirit upon us. At least one we embrace. Because we’re an Entertainment Town, a lot of her slows down this last week of December, and some of us get to slow down with her. It’s a little bit colder (low 60s, high 50s if we’re lucky), a little bit emptier (only a half-hour wait at Greenblatt’s on Sunset), but indeed, somehow, a little bit cheerier despite the year it’s been. (We won’t discuss the election but if losing Alan Rickman and Harper Lee and Muhammed Ali and Garry Marshall and John Glenn and Edward Albee and — the mind boggles — Prince and David Bowie and Gene Wilder weren’t enough, a day after losing Carrie Fisher, we lost her mother, Debbie Reynolds; both of them on the heels of George Michael.) Well, despite it all, even L.A. — we aren’t defeated — embraces the holidays, consciously reveling in the tinseled haze.

It doesn’t matter who you are, one can’t help but feel nostalgic at this time of year. The holidays do that to us, don’t they? Now, for those of you reading this series (and we thank you) that word “nostalgia” probably has an immediate connotation: Old movies; Louis Armstrong on vinyl; your Grandma’s China pulled out for that special dinner — all those are wonderful. But it can also mean a wistful embrace: Remembering where you were as a child and who you were with, probably relatives and friends who have since passed. The food, the music, some of it corny, sure, but it all helps — at least for those moments you’re embracing. Because sometimes that’s all it takes, a moment, and you’re out of the jostling of real life and back in that old movie, that Armstrong song, Grandma’s dinner. Considering this series is on Billy Wilder, I can’t help but think of the boys of Stalag 17 (the barrack but, sure, it’s the name of the movie, too) hanging their dog tags on the little Christmas tree, a centerpiece in the only world they have left.

Were they defeatists.

But we’ll get to that.

A year ago, November 2015, my wife Diana and I were in Lyon, France. It was Thanksgiving Day (for us two Angelinos), we’d just been married in Paris, and we were continuing our honeymoon in Lyon for two reasons. One, Les Halles de Lyon, which, if you’re a foodie at all, you must visit. Think of an indoor Farmer’s Market on steroids (this one the size of a city block with sixty or so individual merchants: coffees and pastries and meats and cheeses and oysters and wine). And, two, if you’re a movie lover at all, Lyon’s Musée Lumière (The Lumière Museum). For true fans of cinema — beyond movies, I’m talking cinema now — it’s Eden.

Antoine Lumière, a successful portrait painter, was quick to see the financial reward of photography and abandoned his own art to set up a factory manufacturing and supplying photographic equipment. His two sons, Louis and Auguste — already technical wizards in their teens — happily followed suit.

Briefly — you can find all this online or, dare I say, in a book — the brothers aimed to overcome the problems, or rather limitations, of Edison’s inventions. The bulky Kinetograph (Edison’s movie camera) was an enormous piece of machinery — as in you couldn’t move it, much less out of the studio. The Kinetoscope (Edison’s peephole viewer) only allowed one person to screen the film at a time. By early 1895, the Lumière Brothers invented their own device combining camera with projector and — at only 16 pounds — they could take it practically everywhere. They called it the Cinématographe.

Though admittedly debatable, their La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory), which I talked about briefly in my They Died With Their Boots On write-up for my Errol Flynn Top 5 is widely considered the first film (you can view the short here), mostly because of its elaborate premiere 28 December, 1895 at The Grand Café in Paris (remember, this is the first time people sat together watching a projected moving image).

Going to The Lumière Museum, stepping out of The Metro as Diana and I did a year ago, you can spot it immediately, because it looks like a mansion. That’s because it is a mansion, the still monumentally elegant Lumière family home sitting in the same spot it did a hundred-plus years ago. The factory, which once butted up to the house, is now gone (though part of the land is now the Institut Lumière Cinémathèque). (And, no, the street where the Lumières placed the camera to shoot those workers leaving the factory wasn’t named Rue du Premier-Film then.) But the house — and what they could keep of the factory (a gorgeous half encasing, half artistic reproduction of said exit) — is remarkable.

In 2002, Dominique Paini, then Director of the Department of Cultural Development Centre Georges Pompidou, designed the layout, with three floors and twenty-one rooms (just in the mansion) open to the public. It of course showcases the Cinématographe but also the Edison Kinetoscope and The Chronophotographie Demenÿ (another pioneering process in Victorian Cinema). It also shows original “magical lanterns” — when you’d look through a slot in a circular plate where there were a series of static images and when you spun the plate the images “moved” — and initial Photorama (360 degree image), Autochrome Plates (Color) and a Relief Projector (yes, 19th-century 3D). And, remember, these aren’t just stills but moving images. Beyond the moving image, The Lumière Brothers dabbled in sound, mechanics and even medicine (designed by Louis, the “hand clamp” saved amputees in World War I, and, designed by Auguste, the “fat tulle” — large strips of the material — healed burns).

No, Cinema Eden hardly does it justice.

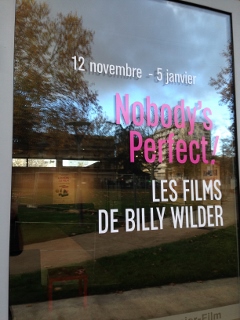

Stepping out of the mansion proper onto the grounds — bright and sunny but still cold in France in November (perfect for a honeymoon) — we walked through the courtyard to the famous factory exit location and I could see the Cinémathèque there. Though closed that morning, we could see an ad for the current festival so I walked over to see what it was. And what was it? (Wait for it.) Nobody’s Perfect! Les Films De Billy Wilder. Now, Diana and I have always been a fan — we have a Sunset Boulevard insert hanging in our foyer — so I took the photo you see above (we wished we could have come back that night to see something but sadly we could not). I had no idea that seven months later Mr. Rohrer and I would be writing about Mr. Wilder. Coincidence? Sure, and I think a wonderful one now, since I could use it to talk about all this.

There’s that line Rohrer and I have been trip-tyching throughout the series – “Nobody’s perfect” — and that remains true. But completely unplanned, unprompted, un-searched-out-for, there was a perfect Wilder pop-up in another retrospective. And it goes back to what I was saying earlier in the series about his enduring legacy. No Jerry Lewis jokes, please, but even the French — wildly aristocratic in their view of American Cinema (and no “auteur” jokes, please) — find Wilder enduring, at least enough to showcase his films for almost two months. (I wish I could have at least stepped inside the Cinémathèque to see what was being shown, who was speaking, et cetera. Alas.) Still, it was nice to walk away from a museum about cinema — perhaps the museum about cinema – that still actively shows and showcases movies so well. (To digress as I tend to, yes, this is where Quentin Tarantino gave his Master Class this year [October 2016]; incidentally choosing as one of his 15-feature retrospective, Wilder’s The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes.)

France isn’t the only group to continue finding Wilder so enduring. Our own American Cinematheque, founded in 1981, recently screened Some Like It Hot, still number one on AFI’s “100 Best Comedies”. This from American Cinematheque’s own website:

WHY DOES L.A. NEED A CINEMATHEQUE?

Located in the filmmaking capital of the world, our purpose is to provide Southern California audiences with the broadest possible movie-going opportunities. Unlike an annual film festival, we screen year-round and are able to provide both the public and filmmakers with a permanent venue to enjoy and study film on the big screen.”

Hear, hear! As Mr. Tarantino himself says, it’s the same reason he shows movies at his New Beverly Cinema in 35MM: because you should. Anyway, just last month, they screened Some Like It Hot and, in conjunction, posted this fun excerpt from Dennis Bartok’s & Jeff Joseph’s new book A Thousand Cuts: The Bizarre Underground World of Collectors and Dealers Who Saved the Movies [August 2016] (this is Mr. Bartok speaking now):

In the 1990s, I made a number of attempts to get Wilder to come out for a tribute. He dodged one invitation with, “I’d like to tell you that I have to rush down to San Diego in an ambulance to see my sick sister, but the truth is I just want to stay home and watch football.” Then [American Cinematheque] took over Grauman’s legendary 1922 Egyptian Theatre and launched what became a $15 million renovation. As part of their fundraising campaign they updated their prospectus with quotes from well-known filmmakers. Most, like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Spike Lee, offered earnest, boilerplate “We think the Cinematheque is a really terrific idea” statements. Then on January 14, 1998, I was sitting at my desk when our Office Manager Nancy came to the door. “Dennis,” she said, startled, “Billy Wilder is here to see you.” I look up dumbfounded as the 91-year old shuffled into my office. And he fixed me with a blunt glare: “Do you take dictation, young man?” I mumbled yes and then he delivered the following in his thick Austrian accent:

“Once upon a time, I knew a blind director. He was legally blind. He didn’t want any guide, anybody with a white cane or a seeing-eye dog. He directed a few good pictures, really remarkable for a blind man. Then one day — wonder of wonders — he saw. The idea that he could now see what he directed before, instead of just shadows and walls. What’s more, he could write. Boy, did he rewrite! Two pictures altogether — one is still on the shelf at the studio, the other went straight to the toilet. He died before he was 70. Poor schnook!”

Wilder insisted I print it out so he could proofread it; he added a punctuation mark at the end of “Poor schnook!” dated and signed it, and then disappeared as mysteriously as he came. To this day I have no idea what Wilder’s bizarre parable means. Is he the blind director who gets the double-edged gift of sight? And I’d even doubt the whole incident occurred except that I was there and the Cinematheque printed his testimonial in their fundraising brochure.

I shared that in (most of) its original length because I like the story, sure — I love “What’s more, he could write. Boy, did he rewrite!” — but also, again, to show there are a lot of us out there still talking about Wilder (and I don’t think many have heard that particular nugget). Now, it should be no surprise, of course, that we’re still talking about Wilder; exalt him, berate him, the man made enough great pictures that we should (at least) be talking about him. But I continue to digress.

It’s the last week of December here in Los Angeles. Perhaps that sounds odd because, of course, it’s the last week of December all over the world. And I, at least, can’t help but be nostalgic. Something to embrace, I suppose, given the dark year. Yes, I go to the wistful.

I mentioned earlier that I couldn’t help but think of the boys of Stalag 17. That’s the name of the barrack in which they’re imprisoned, but it’s also the name of the Billy Wilder film: Stalag 17 (and, yes, it’s in my Wilder Top 5). There’s the scene (we’re well into the picture’s second hour now) where — they’re POWs, remember — they use their dog tags to add some sparkle to what they can make of a Christmas tree. “A centerpiece in the only world they have left,” I wrote.

“Were they defeatists.”

Which they aren’t at all, of course, including Sefton who takes a hell of a beating throughout only to give that great smile and half-salute as he exits. And I think that’s a fair note to end my half of this ten-part series on Billy Wilder, a Writer/Director — forget labels, the man was a Storyteller — often thought of as cynical and hard and (even in his comedy) biting. And he was, partly, all those things. But only partly because, when you really look at his pictures, there’s a tremendous amount of hope in them.

Fully plunged, clothes-on, in Phyllis Dietrichson’s deep end, Walter Neff still looks after dear little Lola (and I stand by Edward G. Robinson’s last line). Knowing he’s trapped in Norma Desmond’s world — giving into it — Joe Gillis still claws out enough to write with Betty Schaefer. Given the reveal he’s fallen in love with a man, Osgood Fielding III resides, well, it could be worse. And C.C. Baxter gives up his world (Rubik’s Cube as it is) for just the possibility of a real relationship with Fran Kubelik: In many ways Wilder’s darkest (and therefore best) story, our guy professes love and happily settles for a card game.

Defeatists none.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Oeuvres Total, to date:

Part I by Michael Holland

Part II by Jason Rohrer

Part III by Michael Holland

Part IV by Jason Rohrer

Part V by Michael Holland

Part VI by Jason Rohrer

Part VII by Mr. Holland

PART VIII by Jason Rohrer

Part X coming soon’¦