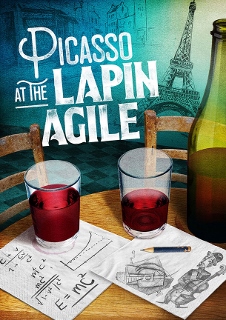

THEATER’S BLUE PERIOD

Steve Martin wrote Picasso at the Lapin Agile in 1993. The offbeat meta-theatrical play opened at Chicago’s Steppenwolf, went to Los Angeles’s Westwood (now Geffen) Playhouse, and ended up in New York for a relatively successful run at Off-Broadway’s Promenade Theatre. The story (well, not “story” really; it’s more of an idea) concerns two of the twentieth century’s greats in art and science’”Pablo Picasso and Albert Einstein’”on the occasion of their fictional meeting at the bohemian Montmartre, Paris establishment, the Lapin Agile (a location that Picasso actually haunted in real life). Now, Barry Edelstein directs a new production for The Old Globe.

Set in 1904, it is the period just after the fin de siècle at the tail end of La Belle Époque, when Paris was the world stage for innovation, science, technology, and the arts’”a city which only 15 years earlier hosted the 1889 World’s Fair; the Eiffel Tower was built to serve as the grand entrance. The action takes place just before the 23-year-old Einstein, still a patent office agent, was to publish his theory of relativity, and two years before the 25-year-old Picasso’”a destitute, wandering bon vivant, seducing women with his irresistible Spanish passion’”created his groundbreaking painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

These serious achievements and the larger than life personae of these two innovators are given a light touch of fancy. Yet even with some brilliant musings, the engaging characters spout enough of Martin’s gag-like lines to make it a bit corny and juvenile. The smart script isn’t prolix, but at 100 minutes it feels overwritten. And even as we understand Martin’s intention, the denouement feels tagged on. Martin takes a big risk, but it seems like the play goes off the rails. With such a great set-up, the ending almost feels like a betrayal.

These serious achievements and the larger than life personae of these two innovators are given a light touch of fancy. Yet even with some brilliant musings, the engaging characters spout enough of Martin’s gag-like lines to make it a bit corny and juvenile. The smart script isn’t prolix, but at 100 minutes it feels overwritten. And even as we understand Martin’s intention, the denouement feels tagged on. Martin takes a big risk, but it seems like the play goes off the rails. With such a great set-up, the ending almost feels like a betrayal.

The show opens with mugging bartender Freddy (Scrubs‘ Donald Faison, who really should stick to sit-coms) setting up the bar for the day; also there to run the bar is his girlfriend Germaine (Luna Vélez, often going wholly contemporary’”but then again, so do some of her castmates). First to patronize the bar is the elderly Gaston, a regular (Hal Linden, cashing in on a strong theater background by getting laughs even when lines weren’t funny); the biggest laughs of the night involved Gaston’s prostate problems. Soon, we meet a harried and buttoned-up Einstein (in both dialect and appearance, a sincere and uncannily accurate Justin Long), who’s waiting for a red-headed date.

The banter at this point is natural and humorous, but soon the fourth wall is broken as Freddy jumps into the house and grabs a patron’s program to point out that Einstein has entered the scene early. It’s easy to get that Martin is already winking at his own playwriting, but the self-deprecation is dramatically unsound; Martin will interrupt his impetus throughout the play. He offers some fascinating philosophy without being heavy-handed, and occasional humor without sacrificing character, but what he sorely needs is Tom Stoppard.

Some of the most entertaining and thought-provoking dialogue involves philosophy. Two of my favorites were: Picasso’s agent Sagot (a bombastic Ron Orbach) offering a humorous explanation as to why it’s hard to sell paintings of Jesus and sheep; and Picasso and Einstein’s debate about the importance of science and art, and their equal impact on society. (The well-cast Philippe Bowgen, dripping in sex and sensuality, more than validates the famed painter’s notorious reputation as a Lothario; Picasso is regarded as one of the top ten womanizers of the twentieth century.)

Then there is Schmendiman, an inventor and a product of Martin’s imagination (Marcel Spears goes for Vaudevillian huckster-type here). An inventor of a building material, Schmendiman is certain that he will be the third in the trifecta of those who will hold the greatest influence over the developments of the twentieth century; it’s a terrific way for Martin to throw in ideas on capitalism and the nature of genius.

Then there is Schmendiman, an inventor and a product of Martin’s imagination (Marcel Spears goes for Vaudevillian huckster-type here). An inventor of a building material, Schmendiman is certain that he will be the third in the trifecta of those who will hold the greatest influence over the developments of the twentieth century; it’s a terrific way for Martin to throw in ideas on capitalism and the nature of genius.

Liza Lapira never really catches on fire doing triple duty as a Countess (the redhead); an ardent female admirer of Schmendiman; and Suzanne, Picasso’s muse and lover (her largest role). The stage is rife with actors who mostly work in TV, and the play, it seems, calls for a special theatricality (a combination of burlesque and earnestness, maybe) that only a handful possess (Linden, Long, Bowgen, and Orbach). Since Edelstein and The Globe are going for diversity and fame over perfect casting here, it’s no accident that there is a discrepancy in acting styles resulting in a lack of true comedy.

Here’s what works: The show’s script is dense with debate and dialogue about what’s real in art, science, and the impacts both make on the future to come. What’s nice about the density is that it doesn’t take itself too seriously; the intellectual back and forth merges with clever gags and bawdy humor. We get the seriousness of science, the transformational power of art, the convergence of the two, and the irrevocable impact they will make. When the actors toast the universe, John Lee Beatty’s expansive tavern, a glorious reproduction of Picasso’s art, and Russell H. Champa’s starlight offer one of the most beautiful stage pictures in memory.

Here’s what doesn’t work: For all the insights from Martin, we leave the theater uninspired. It’s a swirling cascade of ideas that never meld into the storytelling necessary to move or touch us. It’s an awesome set-up that suddenly delves into a message that genius comes in many forms: Martin’s script calls for a mysterious “visitor” to enter toward the end, but the identity of the time traveler (Kevin Hafso-Koppman) is obvious from the start. Having an unnamed blue suede shoe-wearing visitor show up from the future feels like a letdown because we have difficulty tying this metaphysical event to the rest of the play. If any time in the theater ever called for an “Aha!” moment, this would have been it.

I assure you that you will never see a more beautiful production of this too-often revived play, but I’m also convinced that without Martin’s name, it would never have been produced at all. Many label Martin a “genius” and that may be true. But a genius what? Einstein was a genius physicist. Picasso a genius painter. Elvis (oops, I mean, The Visitor) a genius performer. This enterprise feels like Martin making up for the fact that, while he’s a good writer, he’s not a genius playwright. Picasso at the Lapin Agile is an extended SNL skit, a mix of bawdy humor, existential angst, and a bittersweet foreshadowing of the calamities of the century yet to unfold for those on stage. All of this is enough to keep you engaged to a point. Brainy, sometimes funny, sometimes embarrassingly silly, it’s simply not a great play.

Picasso at the Lapin Agile

Donald and Darlene Shiley Stage

The Old Globe

1363 Old Globe Way in Balboa Park

ends on March 12, 2017

for tickets, call 619.234-5623

or visit The Old Globe

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

“…without Martin’s name, it would never have been produced at all. ”

Thank you for calling this out in a published review. I believe this is the third Steve Martin work that the Globe has programmed since David Edelstein has taken over. If only Edelstein had taste and would have programmed 3 Tom Stoppard plays instead.

I have seen Picasso at the Lapin Agile twice in other productions. I think it’s intellectual frippery, gimmickry, and sophistry.

He’s no Ionesco…