SINKING INTO THE STEPPES

Running invisible endurance feats, the characters of Anton Chekhov expose what Henry David Thoreau called “lives of quiet desperation.” When the good doctor’s creations, compassionately but uncompromisingly presented, break loose from boredom and emotional paralysis, it’s only to crash into unrequited love. Like T.S. Eliot’s forlorn J. Alfred Prufrock, they measure out their lives in coffee spoons (or swigs of vodka), dreaming of a future where they could never belong. Bereft of illusion, they expect to be forgotten’”unlike us, who don’t expect it.

It’s said that every Chekhov play begins as a comedy and ends as a tragedy. The truth is trickier: The characters trapped in Uncle Vanya, now presented by Goodman Theatre in Annie Baker’s bracingly direct adaptation (from a literal translation by Margarita Shalina), achieve neither extreme. Cursed with consciousness, they’re too aware of their faults to become caricatures but, mired in melancholy, they fall short of monumental suffering. However depressed and unrequited, these leaking lives have a perverse instinct for thwarting each other. They either love too soon or too late or the wrong person or succumb to the inertia of vodka and the balalaika. They’re paralyzed between living in the past or future but never the moment. These drifters never move.

An exercise in entropy, Uncle Vanya delivers the dead-end desperation and mid-life crises of the title character and his angst-ridden household. In this hotbed of unrequited love, elaborate regrets, emotional paralysis, and vodka chugging, the characters punish each other and themselves for the dreams that died. Never has a better doctor offered patients a grimmer diagnosis.

The fault lines beneath this critically bored family are about to snap. Working from Baker’s no-nonsense reworking, artistic director Robert Falls captures the festering resentments that explode when the pompous professor who has milked this household for a lifetime dares to try to sell the estate. Vanya, played with apoplectic rage by Tim Hopper, typifies his clan: Deadened by resentment, he has taken his disillusions to the brink of suicide or homocide. Ironically, though he no longer feels “lit from within,” Vanya remains the one character who does something. Furiously protecting his potentially disinherited niece Sonya (soulfully suffering Caroline Neff, burdened with an incongruous “valley girl” inflection), he grabs his gun’”and characteristically misses his nemesis. It’s inevitable: Any action in this bittersweet world changes nothing. One speaks for all: “I never lived!”

Sturdy work comes from an addlepated Mary Ann Thebus as the nattering nanny who, resigned through religion, dismisses the others as “God’s mockers.” Masterfully miserable, David Darlow festers and succumbs almost galvanically as the envious and self-pitying professor. Marton Csokas sputters with impotent indignation as the alcoholic doctor who lives in an invisible future, means well, and does nothing.

Playing the much-manipulated Sonya, Neff is sardonically contemporary as the next sacrifice in this clan’s cycle of despair. Kristen Bush as the professor’s lovelorn trophy-wife, her miseries at least picturesque, proves magnificent in her elegant summer gowns by Ana Kuzmanic. An almost mummified Marilyn Dodds Frank plays Vanya’s all-enabling mother with maddening petulance, while Larry Neumann Jr. is goofily endearing as “Waffles,” their impoverished neighbor and lifelong dependent.

Muted or manic, at times the Method-y mumbling or scenery-chewing histrionics of these introverted characters contrasts with the manic episodes: The result is a schizophrenic amalgam of frenzy and torpor. Would it be that hard to supply some projection (which need not be declamation) to this too-quiet desperation?

No question, the beleaguered look is right from the start. Todd Rosenthal’s crumbling, distressed set literally leaks during a huge second-act rainstorm, its faded grandeur a metaphor and a half. This manse has seen better centuries.

So, yes, during these near three hours we really feel life passing by these characters. It’s hanging heavily over us as well. With more glacial pauses and enervating longueurs than Pinter, Falls conveys their boredom (felt and shared) a tad better than needed.

Perhaps this volatile mix of concentration and extroversion creates an audience pushback: Judging from the condescending chuckles heard on opening night, Uncle Vanya, especially when updated, comes too close for comfort. But the dead ends that these characters discover with almost suspicious eloquence and astonishing perception were never confined to the 19th century. The sad alternative to suffering with them is laughing at them. But why bother? The joke’s on us.

photos by Liz Lauren

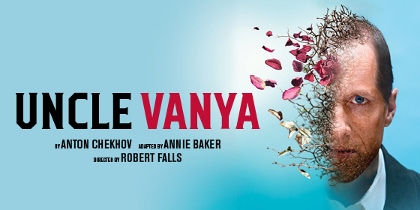

Uncle Vanya

Goodman Theatre

Owen Theatre, 170 North Dearborn

ends on March 12, 2017 EXTENDED to March 19, 2017

for tickets, call 312.443.3800 or visit Goodman

for more theater info, visit Theatre in Chicago

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Beautifully written review. This is my favorite drama.