A LENGTHY BUT LOVELY OFFENBACH

Just as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart died in the middle of writing his famous Requiem so did Jacques Offenbach die composing his fantastical opera Tales of Hoffmann. Both works have been seen as highly personal compositions: Mozart writing his own requiem and Offenbach standing in for Hoffmann, his protagonist. The similarities do not end there, however. Requiem and Hoffmann can both be seen as new departures musically for their composers, who tackle more macabre themes and styles. Both unfinished compositions have also provided plenty of manuscript material for publishers, composers and musicologists to complete, revise, rewrite and print. In consequence, few audiences ever see the same version performed twice.

The edition of Tales of Hoffman LA Opera is now presenting is that of Jean-Christophe Keck and Michael Kaye (the Keck-Kaye edition). Without going into too many details, one can say that it tries to be faithful to Offenbach’s surviving manuscripts without being fastidious about it. Since there is sung recitative rather than spoken dialogue, and the inclusion of three Hoffman stories, one of which is in  a different order than Offenbach’s original, Marta Domingo’s production lasts close to four hours, including two intermissions. The evening, while musically strong, is taxing in length.

a different order than Offenbach’s original, Marta Domingo’s production lasts close to four hours, including two intermissions. The evening, while musically strong, is taxing in length.

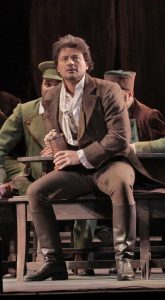

Tales of Hoffmann reimagines the life and loves of writer E.T.A. Hoffmann. Its structure is quite transparent: a prologue and epilogue frame three of Hoffmann’s stories. In the prologue, we learn that Hoffmann (played by tenor Vittorio Grigolo) has been unlucky in love. He is visited by the Greek muse of poetry (mezzo-soprano Kate Lindsey), who disguises herself as the young man Nicklausse. As such, she wants Hoffmann to forsake all other loves for her, including his current love interest, Stella (a small role played by soprano Diana Damrau). Although the two do not work in concert, the muse is aided, in a way, by the nefarious Lindorf (bass-baritone Christian Van Horn, flown in from Dallas to cover for a vocally ailing Nicolas Testé), who is a rival for Stella’s affections. Lindorf and Nicklausse, therefore, can be seen as competing influences on the protagonist Hoffmann, the former evil and the latter good.

During the epilogue, the muse reveals all three false loves, as well as Stella, to be one and the same love. In order to underline the significance of this idea, some productions have cast a single singer in the role of all four female characters. And that was the original announcement for Damrau, whose bronchial infection (the same infection perhaps that saw her husband Nicolas Testé indisposed) caused her to sing only two roles. Covering the four women of Hoffmann were, by order of their appearances: So Young Park, bright and clear-as-a-bell as Olympia; mezzo-soprano Kate Aldrich as the sensuous seductress Giulietta; and the passionate Damrau, sounding vocally splendid as the sickly Antonia (who sings herself to death) and the actress Stella – with nary a sign of her bronchial afflictions.

For now, we will just have to wonder if Damrau has the versatility required to sing Olympia’s technical coloratura and Giulietta’s dramatic mezzo-soprano, but this production’s casting of different singers allows for a very special turn. Undergirding the complex plot is Offenbach’s playful and lush orchestration, which includes music for the harp, and challenging vocal settings – above all, Olympia’s famous “Les oiseaux dans le charmille.” South Korean soprano So Young Park’s virtuosic performance of “The Doll Song” was a highlight. The beauty of the vocal setting with its ascending and descending lines, the technical mastery required to sing them, the perfect control with which Ms. Park executes them, her dramatic ornamentations, youthful energy and humorous touch all combine to make this one of the most overwhelming and unforgettable of experiences.

In contrast to using multiple actresses, some of the male characters who appear in multiple stories under varied guises, such as The Four Villains (Lindorf, Coppelius, Dapertutto and Dr. Miracle) and the The Four Servants (Frantz, Andres, Cochenille and Pittichinaccio), are played by just one singer, thereby highlighting the continuity and persistence of their characters. Mr. Van Horn acted stupendously as The Villains, grounding each of his characters with a grandstanding malevolence, aided by his rich, substantial tone. And Christophe Mortagne added a much-needed humor to the proceedings; his servants could easily have come off the pages of a steampunk Dickens novel.

Grigolo and Lindsey are well-matched in their acting and youthful vigor. He, especially, bounds about the stage–whether drunk on love or alcohol or both–with a gloriously strong but smooth voice that never wavered once (I was definitely OK with his vocal pyrotechnics, but his showing off also added to the production’s length). And while no one can argue with Lindsey’s luscious and milk chocolaty mezzo, she simply lacks power, (a similar problem in LA Opera’s Cenerentola). Plácido Domingo’s conducting was fine, but left too much room for singer interpretation in an evening that needed a firecracker to keep things moving along (I mean, come on, this isn’t a very substantial piece). His wife’s production doesn’t set new standards for the interpretation of Hoffmann, but she ensures that we have some funny stage business, plenty of movement, and visually appealing scenery and costumes that capture the aesthetic of the period.

The Tales of Hoffmann

LA Opera

co-production with the Mariinsky Theater

and Washington National Opera

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 North Grand Ave

ends on April 15, 2017

for tickets, call 213.972.8001 or visit LA Opera