PROVOCATION PLUS DISRUPTION’”

2017 GETS ITS PLAY!

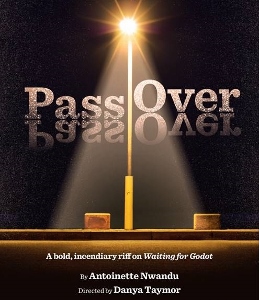

Ever since artistic director Anna Shapiro took over Steppenwolf Theatre Company, the Chicago mecca hasn’t been afraid to upset an audience. Subversive fare like Good People, Linda Vista, Grand Concourse and Straight White Men discouraged easy expectations and shook up conventional assumptions of right and place. Pushing this intransigence to the limit (not to mention its own theatrical luck), Pass Over almost goes a bridge too far.

Ruthlessly paced by director Danya Taymor, Antoinette Nwandu’s world premiere transforms Waiting for Godot into an urban nightmare with a Trump twist. It’s no longer the achingly repetitious vaudeville of colorful hobos waiting for a break in their boredom. Samuel Beckett’s allegory is now a topical gloss on the futility felt by young black men and the “genocidal” violence they fear and face from the police (here “po po”). And in Nwandu’s raw translation, “Godot”’”a white overseer named “Mister”’”does show up, with a vengeance.

The pre-show music, happy tunes from Broadway classics, luxuriates in the false nostalgia of American optimism. What happens in Steppenwolf’s upstairs space is a different kind of make-believe: This Vladimir and Estragon (who also recall George and Lennie in Of Mice and Men, as well as Godot’s ironically named slave Lucky) are best buds Moses (Jon Michael Hill) and Kitch (Julian Parker). Keeping it real, they hang out at night under a ghetto lamppost and near a discarded sink. (Interestingly, Wilson Chin’s stark set is a slab surrounded by sand, eerily resembling a huge child’s playground.)

These homeboys, their dialogue drawn from the students the playwright met while teaching community college, engage in horseplay, in-jokes, and game-playing (including, over and over, calling each other “the N-word”). “Talking shit” (to quote the press release), they indulge in escapist fantasies about “getting off this rock” and out of “Egypt” to the “Promised Land.” They play at devouring gourmet food, aping rich-folk mannerisms, dabbling in drugs, finding and keeping girlfriends, and, well, not getting shot. Above all, these guys want to “pass over” to a better future even as stray bullets “pass over” them at irregular intervals. Almost mute with grief, they sink into a litany of dead friends killed by cops.

A godawful Godot, the third player is a mysterious white man in an ice cream suit named Mister (Ryan Hallahan)’”though he gives himself away by accidentally calling himself “Master.” Speaking a throwback countrified patois (“gosh, golly, gee”), he has gotten lost trying to bring food to his mother. Instead he unpacks his picnic basket and regales the suspicious duo with a first-class feast, which Kitch readily accepts though Moses remains wary. Sinisterly passive-aggressive, Mister can seem kindly (sardonically singing “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning”), then stridently explodes into a plantation owner’s “I own it all!” or orders them to “know your place.”

Managing to get more real and still stranger, this taut one-act delivers two very different and equally unsubtle encounters with “The Man,” namely Ossifer (also Hallahan). This racist young cop is brutal enough to tempt these survivors into considering suicide (“Kill me now!”). Too predictably, any attempts at self-help are met with overwhelming oppression. But, turning the tables, Ossifer is later hideously tortured, as Moses, declaring he’s not a thug, pimp, gangbanger or deadbeat, somehow pulls off one of his namesake’s famous plagues.

Finally, thwarting this apparent revenge, rampaging out of the audience (as if we sent him), and proclaiming “We stood our ground!,” Hallahan’s Mister cuts off the play. Pass Over ends with a horrible hate crime, sickeningly taking back the night and making America “great” again.

Pass Over is an 80-minute roller-coaster, dangerous with pungent poetic personifications of white power and black victimhood. Nwandu boldly (or selectively) shapes (or simplifies) this microcosm to suit her indictments: All the bullets come from “white” guns. These targeted young men have none of their own. Here hope is just a four-letter word.

Pass Over is an 80-minute roller-coaster, dangerous with pungent poetic personifications of white power and black victimhood. Nwandu boldly (or selectively) shapes (or simplifies) this microcosm to suit her indictments: All the bullets come from “white” guns. These targeted young men have none of their own. Here hope is just a four-letter word.

The three performances are true enough to make us unintended eavesdroppers, the script as angry as it’s eloquent with street slang and gallows humor. A cynic could argue that, even as it voices the dreams of the seeming defeated, Pass Over caters to white-liberal guilt and big-city paranoia. No question: Uncompromising, in-your-face, and pulling no punches, Nwandu’s agitprop shocker will find its fullest form in the post-show discussions (whether on stage or off) that increasingly play a crucial part in the Steppenwolf experience.

Will or can a North Side audience admit that Pass Over testifies to a world we’ve made as well as live in? That’s a huge uncertainty the play refuses to resolve.

Pass Over

Steppenwolf Theatre Company

Steppenwolf’s Upstairs Theatre

1650 N Halsted Street

ends on July 9, 2017

for tickets, call 312.335.1650 or visit Steppenwolf

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago