BLUES WITHOUT NOTES

It takes a play to raise a village. Here it’s East Harlem, a killing field with 8 homeless shelters, 36 drug and alcohol treatment centers, and 37 mental health treatment facilities underserving a needy neighborhood. Cursed with N.Y.C.’s greatest unemployment, it contains, as the New York Post says, “the most dangerous blocks in the city.” The only escapes are in the front and strictly for fire.

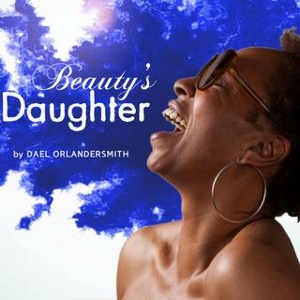

It’s also the core character behind six lives kinetically depicted by Wandachristine in American Blues Theater’s Chicago premiere Beauty’s Daughter, now playing at Stage 773. Created in 1994 by Chicago poet/playwright Dael Orlandersmith, this is an Obie Award-winning solo show about broken people seeking fixes in soliloquies and music.

It’s also the core character behind six lives kinetically depicted by Wandachristine in American Blues Theater’s Chicago premiere Beauty’s Daughter, now playing at Stage 773. Created in 1994 by Chicago poet/playwright Dael Orlandersmith, this is an Obie Award-winning solo show about broken people seeking fixes in soliloquies and music.

Employing what could be called a no-exit strategy, Ron OJ Parson’s 90-minute revival conjures up a curious contradiction—dynamic dead ends in souls struggling against drugs, the past, heartbreak and themselves. Sometimes the un-distilled poetry of these monologues can pile up images into incoherence. But, even when opaque, these cascading confessions from a multifaceted actress create a whole much bigger than the parts.

Caitlin McLeod’s serviceable setting focuses on the corner of a parlor strewn with keepsakes and containing an old record player that will trigger memories through music (Eric Backus’s deft sound design). There, Paul Deziel’s potent projections and vintage video paint the walls with images to illustrate dreams and obsessions. Michael Alan Stein’s deftly switched costumes contrast and control the sextet. Jared Gooding’s lighting alters moods in instants.

The central subject is Diane, a tough 35-year-old woman/witness who insists she’s “no punk bitch,” even as she admits to being dumped in Dublin by a cad named Cal. The daughter of a man called Beauty, she keeps lurching from hope to hurt, too hungry for love to learn from bitter experience.

Orlandersmith’s other creations include a Puerto Rican reefer boy named Paco: The teenager implores Diane to let him pay her $10 per page to write his English term paper on minority writers and their influence. Afraid to get lost or get shot, this homophobic kid is all too ready to pass down the abuse he gets from a brutal dad.

Also begging for help is a homeless blind musician whose better days now seem to be the only ones. We next meet “Mother” Mary, Diane’s blues-singing foster mother who recalls a lot, including a precious necklace that will become a kind of talisman when she dies. Then there’s a 31-year-old Italian Lothario, a fish-market worker who feels “trapped” in a miserable marriage. He meets Diane at a wedding and considers her his muse (returning to play the saxophone he abandoned years before).

Finally, there’s Diane’s always-angry, drugged-down mom, a former stripper and self-admitted female “powerhouse.” Toxically mourning her late love Arthur—with whom she could jitterbug into joy—she berates an unseen Diane, mainly for being born.

Diane returns, delivering a valedictory for all the living ghosts of East Harlem, especially the prostitutes (“The only thing that separates me from them is the books in my room”). She curdles at how love means desperation but mellows over how music matters all the more.

Not all six characters will register with their hearers. Sometimes the script’s specifics overwhelm rather than crystallize the sentiments at stake. But what Wandachristine drives home—along with the off-rhythms of half-baked lives—is the cumulative sadness of six survivors. That may be revelation enough.

photos by Michael Brosilow

Beauty’s Daughter

American Blues Theater

Stage 773, 1225 W. Belmont Ave.

Thurs-Sat at 7:30 (except Sat August 5 at 3); Sun at 2:30;

Wed at 7:30 (July 12, 19 & 24); Wed at 2:30 (August 2)

ends on August 5, 2017

for tickets, call 773.327.5252 or visit American Blues Theater