BALLETNOW AND FOREVER

New York City Ballet (NYCB) principal dancer Tiler Peck’s curation of BalletNOW was an elegant and enticing mash-up of well-known excerpts that would satisfy both first-timers and connoisseurs expecting excellence from ballet’s best performers. Three days of shows at L.A.’s Music Center featured a varied repertoire of fast- and slow–paced dances with a few repeated works.

Opening night was a triumph that promised a future third edition to the BalletNOW saga, which premiered in 2015. Although the segments could have been ordered differently for better flow, their diversity makes a strong argument for the production’s goal of drawing more people to ballet.

1-2-3-4-5-6, first seen at the Gerald R. Ford Amphitheater in August 2016, was a short and not completely ballet-centric introduction. The piece starts out with samples of tap (Michelle Dorrance and Byron Tittle) and hip-hop (Virgil “Lil O” Gadson) alongside ballet (Peck) with the music ultimately consisting of rhythmic claps and sharp stomps (developed by Steve Reich). The number evolves as the performers veer away from traditional steps within their genres to include contemporary and break dancing moves when mirroring each other and which they use to travel in a circle around the small, square dance floor laid out on stage. Labeled “improvography,” the spontaneous feeling and dancers’ wide smiles make for an uplifting beginning.

A quick change of pace comes in the form of Chutes and Ladders—NYCB choreographer Justin Peck’s modern dance–style routine created for Miami City Ballet in 2013. Jeanette Delgado and Kleber Rebello perform the piece, which unfolds like a conversation as the duo each take turns waiting for the other to “speak” their passion through leg extensions and dramatic leans depicting an equal partnership in love. Their communicative body language is strong, especially when they are in sync and intricately intertwine their handholds during peaks in the music. Rebello usually chases Delgado with on-stage musicians (Roger Wilkie and Ana Landauer on violin, Shawn Mann on viola and Rowena Hammill on cello) dictating their momentum through String Quartet No. 1. Benjamin Britten’s theatrical melody is full of sudden climaxes and varying speeds of overlapping voices that dictate consistent nonstop movement. Chutes and Ladders‘ romantic edge provides a smooth transition into the pas de deux portion of the program.

The Pas de Deux from Sergei Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet—the only piece featured in all three programs—takes the show into the classics with a look at the balcony scene from the star-crossed lovers’ ballet. This traditional piece may be an odd non sequitur as a wedge between Chutes and Ladders and the contemporary After the Rain, but follows along in the theme of passion and relationships. Choreographed by Kenneth MacMillan for the Royal Ballet in 1965, the steps are very light and soft. Isabella Boylston and James Whiteside of American Ballet Theatre do a good job of portraying the coy yet excited teenagers in their secret meeting. The live orchestra heightens the emotion in each movement, particularly during peaks of sexual tension that manifest when Whiteside lifts Boylston up into the air with her legs open in a V-shape as they make intense eye contact, and during Whiteside’s several back-to-back pelvic hinges aimed at his partner. Combined with their kissing, their physical desire for one another cuts through the airiness of their performance in a coy way that adds a non-conservative edge to what many consider to be an innocent piece.

The following duet, Pas de Deux from After the Rain is a strange stylistic follow-up to Romeo and Juliet because of its jump back to contemporary, but the Christopher Wheeldon’s choreography is stunning and tender in a way that elevates the enchantment of non-classical ballet. First conceived for the NYCB in 2005, the excerpt comes from the final pas de deux in the production. Lauren Cuthbertson and Reece Clarke from the Royal Ballet convey unspoken melancholy that comes through as little eye contact and solemn expressions. Many of the key exchanges between them are hugs, open arm and leg poses than when paired with simple costumes indicate sincerity between the two, and slow, short lifts that keep the dance grounded. Cuthbertson runs her hands gently over Clarke’s face and body to Arvo Pärt’s piano compositions: an arrangement of “Ludus” from Tabula Rasa and Spiegel Im Spiegel, which sound like slowly falling droplets of rain.

Although the juxtaposition to Romeo and Juliet highlights the maturity in this couple’s relationship, After the Rain clashes heavily with the following upbeat George Balanchine ballet.

Allegro Brillante, first created in 1956 and set to Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 3 is the premium example of classical ballet. The piece consists of 10 dancers, including Peck herself and Marcelo Gomes from ABT as the principals. The first cross-company pairing in the program, Peck and Gomes move well together. The choreography is everything one could want from a ballet: sharp elevations; tight turns; and an emphasis on chorus for variety. Of all the performances, this one focuses most on pure ability rather than chemistry with a sharp reliance on the artists to make their common steps look easy, despite the speedy delivery and sharp precision. Gomes’ strength, which he shows off in the skillful abrupt lifts of his partners, and Peck’s quick and charismatic execution of the spin-stop-pose formula are what sell the performance.

The post-intermission ballet which takes up the entire second part of the show and moves the dancing into the category of jazz is Jerome Robbins’ 1944 work for Ballet Theatre (before it became ABT), Fancy Free, composed by Leonard Bernstein. Complete with WWII-era costumes and an old-time New York City backdrop and music, the piece demands full and well-rounded performances. Regular nonverbal acting and the exhibition of a number of different types of dancing—a waltz, a danzón and general athleticism—in the scene where all three sailors-on-leave (Cory Stearns from ABT, Daniel Ulbricht from NYCB and Gomes) compete to win the hearts of the two ladies (Delgado and Peck) they meet outside a bar are what make it charming and memorable. Each character is well-established and does their part to move the plot forward, with Peck and Stearns’ duets providing the most compassionate and whimsical relationship before the mens’ aggression gets in the way during the second half.

It’s important to note how well ballets like Fancy Free age over time. The scene in which all Stearns, Ulbricht and Gomes try to take Delgado’s bag away from her to grab her attention starts off as an excessive tease, but escalates to assault when they grab her and refuse to let go. Audience members laughed at other moments within the dance play such as when the women rejected the men’s cockiness with eye rolls and head shakes. But the scene in which Ulbricht and Gomes chase Delgado after she takes her purse back and runs away from them is downplayed as “men horsing around.” Of all the excerpts and acts, this is the one that suffers most from this phenomenon. Because it ends on a light note and the performances from the dancers were exceptional, audience members received it well. However, it is something that does slightly distract from the ballet by requiring the viewer to constantly remind themselves to separate 1940s’ ideology of what was once considered playful from what society now classifies as harmful.

The multi-layered pieces within BalletNOW and their variety in era, genre and depth form a versatile show that also underscores how far ballet has come within the last 60 years or so. And with Peck’s choice in dancers, the stellar performances ensure that everyone can find something to enjoy.

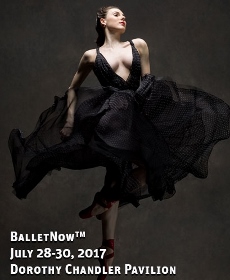

photo of Tiler Peck courtesy of New York City Dance Project

BalletNOW

Glorya Kaufman Presents Dance at The Music Center

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 N. Grand Ave

ends on June 30, 2017

for tickets, call 213.972.0711 or visit The Music Center