ACB’S MODERN THROWBACK

American Contemporary Ballet’s final production of the season reworks an old favorite and breathes life into once forgotten characters from another well-known ballet. The combination of singing and dancing was an innovative conclusion to a trilogy’s worth of education in the classics. Aside from a few logistical problems, the show was very enjoyable thanks to its fun and fast choreography, which proved a visual delight for first-timers and ACB fans alike.

Two performances filled the night. Despite including starkly different styles of movement, the selected scenes in Lakmé (1883), the tale of an Indian priestess who falls in love with a British army officer, served as a precursor for Le Fate in Italia, a new ballet Jones created to delve into the playful personalities of the seven fairies featured in Sleeping Beauty (1890). Both were whimsical and provided insight to 19th-century opera ballets, which Artistic Director Lincoln Jones, whose pre-show lectures can convert a passive viewer into a potential connoisseur and fully-fledged enthusiast, discussed before premiering his work on the 32nd floor of the BLOC building in downtown L.A.

Though thrilling to watch, there were moments of clumsiness visible at the beginning of each piece. A lack of clarity from the program, which was difficult to fish out among the stack of leaflets and envelopes handed to each guest before the show, and the absence of a pause between the Lakmé dances and Le Fate in Italia made it difficult to follow along with the transition of events as well.

Jones’s fondness for Balanchine was a clear influence on both works. For the “Dances from Lakmé,” he removed the plot from the original opera and concentrated on three characters’”Térana (Caroline Atwell), Rektah (Anabel Alpert), and Persian (Emily Smith)’”surrounded by an ensemble of six dancers to make up the Hindu priestesses. The fusion between Indian dance and classical ballet movements was vividly shown in “mudras,” or traditional hand gestures, which became the main focus as the three took turns extending their arms in front of them and flattening their hands in the air, or forming flowers with open palms and flared fingers. Wrist and ankle rotations during angular poses with their raised legs positioned backward at a right angle were visually enticing. However, with so much emphasis on hands, it became obvious when some of the dancers were not in sync; their fingers curled awkwardly as they held their poses unsteadily before leaping toward the back of the dance space at the sound of accelerating violin strings (played by Joanna Lee and Albert Yamamoto).

Choosing to forego the opera’s story made it difficult to understand the purpose behind the selection of the two songs written by Léo Delibes that were included as part of the Lakmé dances. Soprano Anastasia Malliaras did an exquisite job of singing “Où va la Jeune Hindoue” (the “Bell Song”) which preceded the dancing and “Sous le Dôme Épais” (the “Flower Duet”) at the end with another harmonious singer’”mezzo soprano Julia Aks. The fluidity with which their voices meshed together through a range of emotions was mesmerizing. However, the lyrics were references to specific plot points within the opera and therefore made no impact on the free form dance. Even for those curious about the words, it was difficult to follow along with the translations included in the program.

Mozart’s “Donne Mie, la Fate a Tanti” from Così Fan Tutte was a better match of music and movement for Jones’s Le Fate in Italia as a comic song about a man telling a woman that he is frustrated with her seedy reputation. An assistant held up the lyrics on cue cards during baritone David Castillo’s singing. Though better than attempting to follow along with another piece of paper, her positioning next to Castillo and the glare from light hitting the glossy paper slightly distracted from his powerful performance, which set the flirtatious mood for the ballet.

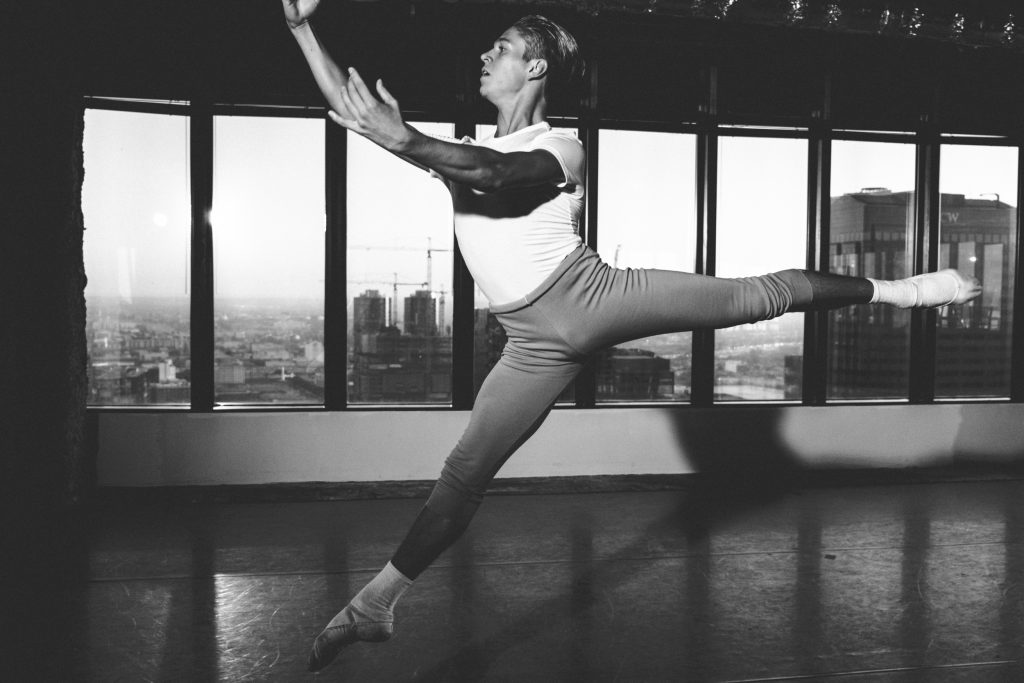

The choreography in Le Fate in Italia was set to Rossini’s music from Guillaume Tell (1829) and showcased fairies, marked by different colored belts, dancing in groups and with two unnamed “uomini” (men) to exciting strings and wind instruments (Andrew Leonard on clarinet and Rachel Mellis on flute). The main attraction for this number was the speed at which they leapt, moved their arms, and lifted one another. Double tours en l’air from the men amid brief scenes in which they pursued their loves were especially fascinating and bold. In some cases, the speed seemed too much, especially in the beginning when a few fairies in the “Ballare Per Sei” portion were not well-synchronized during their duets, spinning out of time with one another until they were able to ease into the rhythm.

Cara Hansvick as La Fata della Diegesi was especially captivating. Her duets with “her man,” played by Colby Parsons, maintained elegance while remaining rapid and coy. Especially in moments when Hansvick would move away from Parsons and look back at him, insinuating that he should follow, then hug him from behind and suddenly release and dismiss him until their next meeting. Canarino, played by Alpert, and her partner, Marc LaPierre were even quicker in their movements and portrayed a younger, more sprightly relationship as a foil to Hansvick and Parsons. Their peaks were to choruses of live singing from the quartet located behind the audience. The harmonies elevated the movement.

The dramatic conclusion to both pieces, which ended with the principal dancers jumping and blissfully being carried away, wrapped up an enchanting season. Despite a few glitches, Jones’s choreography highlighted a new perspective to the progression of ballet by delving deeper into its multi-fascinated past while still embracing the new.

photo by Asilda Photography

La Fate in Italia and Dances from Lakmé

American Contemporary Ballet

The BLOC building, 700 S. Flower St., 32nd Floor

ends on August 13, 2017

for more info and future shows, visit ACB Dances