A PAINTING IS A PORTAL

Art is never still, not just still lifes but landscapes, genre scenes, even abstract configurations and, especially, portraits. Every painting is a time capsule that absorbed everything that was going around it as it was created—and since too. Multifaceted Rohrshack tests of perception, intuition, associations and imagination, they paradoxically measure us against themselves, past against present, permanence against mortality, utterly unchanging and totally changing as we do—so that the same painting can seem to age with repeated viewings. But, of course, it’s life that’s being altered by art.

The beauty part of Jessica Dickey’s The Rembrandt, now in a supple Chicago premiere in Steppenwolf’s Upstairs Theater, is its free-floating conjectures: It focuses (sort of) on a famous work, Rembrandt’s 1653 masterpiece Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer. Thanks to Dickey, this dark double portrait in London’s National Gallery gets seen from the inside out and back. Art imitates life and life returns the compliment.

In 90 minutes, we see five scenes from three different eras, shaped and refracted by the same picture. Far more interesting in what it implies than what it presents, despite Hallie Gordon’s cunning and sometimes compelling staging, The Rembrandt shows how canvases mirror minds, presenting the gift of time to transient, peripheral and limited observers.

In 90 minutes, we see five scenes from three different eras, shaped and refracted by the same picture. Far more interesting in what it implies than what it presents, despite Hallie Gordon’s cunning and sometimes compelling staging, The Rembrandt shows how canvases mirror minds, presenting the gift of time to transient, peripheral and limited observers.

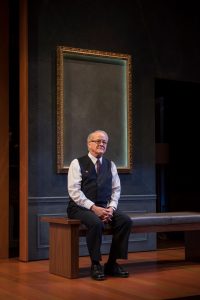

We first see the 364-year-old oil painting in a spacious room in a present-day American art museum. The unseen object is gazed upon by gallery guard Henry (Francis Guinan). This gentle dreamer rhapsodizes over the power of “the Rembrandt” and how the artist used only four colors to achieve a magical play of light and dazzling psychological revelations. The Dutch master turned sitters not into active lifes.

Finding new discoveries in an old and familiar treasure, Henry marvels at the sway of this painting to reveal its secrets at night but to stay “asleep in the light.” Like several characters here, Henry tastes his mortality as he peruses perfection. But, far from criticizing art for isolating us its hold (“alienating” is the ugly term for this), he praises its power to set us apart in order to connect us to the spells it casts.

Finding new discoveries in an old and familiar treasure, Henry marvels at the sway of this painting to reveal its secrets at night but to stay “asleep in the light.” Like several characters here, Henry tastes his mortality as he peruses perfection. But, far from criticizing art for isolating us its hold (“alienating” is the ugly term for this), he praises its power to set us apart in order to connect us to the spells it casts.

A middle-aged gay man whose older lover is dying at home of Stage 4 cancer, Henry is teaching the ropes—and we learn many insider details about museum security and protocols—to a new guard Dodger (Ty Olwin). This young iconoclast, a painter himself, believes we should literally engage art. At first he’s unable to persuade Madeline (Karen Rodriguez), an art student copying the Rembrandt, to literally touch the painting. But, incongruously, Dodger is able to induce both Madeline and even veteran guard Henry to do just that. (Let’s hope this is one case where life doesn’t imitate art: the natural oils and acids in your touch can slowly cause your fingerprint to appear, ruining the painting.)

This “touch therapy” instantly transports them to an elegant studio in the artist’s home in Amsterdam. The previous four actors now play Rembrandt (Guinan), his fretful second wife Henny (Rodriguez), and his child-like son Titus (Olwin). Rembrandt fumes over the Italian patron who has demanded a painting of a philosopher, Henny, over their finances, and Titus over his dad’s neglect. Far from toiling toward immortality, the Rembrandts are caught up in the detritus of daily life and household matters, all the minutiae that underlie the solidity of a deathless creation.

The sole insight into the work to come is that Rembrandt intends to dress his living Aristotle as a contemporary—in 17th-century Dutch attire. He wants, it seems, to convey the universality of philosophy and also to contrast the brevity of this flesh-and-blood thinker brevity with the eternal lastingness of a marble bust of blind Homer.

The sole insight into the work to come is that Rembrandt intends to dress his living Aristotle as a contemporary—in 17th-century Dutch attire. He wants, it seems, to convey the universality of philosophy and also to contrast the brevity of this flesh-and-blood thinker brevity with the eternal lastingness of a marble bust of blind Homer.

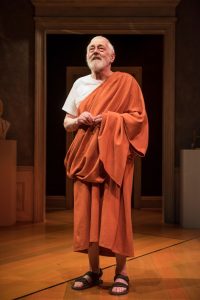

Rewinding the clock even further, we next visit a Greek temple circa 800 BC: Homer himself (the magisterial John Mahoney), no longer a bust in Rembrandt’s atelier or painting, regales us with his preference for oral poetry and his resistance to having his Odyssey or Iliad written down (a silly worry since that didn’t happen until much later). Far from the once and future poet of innumerable pantheons, this small-talking Homer is caught up in gossip, rivalries, and the trivia of his times.

Finally, we return to the present: Dying, Henry’s husband Simon (Mahoney, now devastatingly departing) is a poet pondering the future of his work as much as his own diminishing returns. Death-dogged like the previous scenes, the lovers’ valedictory parting, as they enjoy a last chocolate dessert, is deeply affecting. Swimming against the tide of Simon’s demise, Henry whispers “Don’t die, don’t die,” a plea that nature will always deny. We’re now as far removed as possible from the painting’s impassive perpetuity.

In The Rembrandt a masterpiece that we never see painted (just talked about and, worse, around) fuels some stirring speculation. But that fascination comes more from the situations than the script. In this very structured meditation on life and art’s mysteries, Jessica Dickey has, necessarily or not, little to say about what makes this painting (frustratingly and perhaps perversely never shown) a litmus test for everyone who likes it.

Both broad and nuanced but always persuasive, Gordon’s five actors suit their scenes and stories splendidly, the play’s schematic artifice notwithstanding.

Apart from obsessing on how art lasts but love does not, the five settings, four eras and ten characters (several omitted here since they’re inconsequential “filler”) remain independent items, separate and not always equal. Dickey’s unassimilated whole is not greater than its parts, the scenes pulling apart instead of adding up. But then, if beauty really lies in the eyes of the beholders, no one-act could hope to capture all the resonances from and reactions to “the Rembrandt.” We’ll settle for guesswork.

The Rembrandt

Steppenwolf Theatre Company

Steppenwolf’s Upstairs Theatre

1650 N Halsted Street

ends on November 5, 2017

EXTENDED to November 11, 2017

for tickets, call 312.335.1650 or visit Steppenwolf

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago