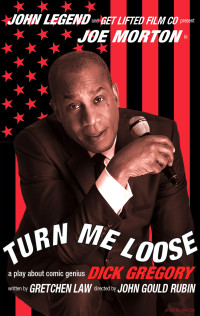

DRY WIT AND RIGHTEOUS OUTRAGE

The best sequence in this largely solo show starring Joe Morton as civil rights activist, comedian, and writer Dick Gregory, is playwright Gretchen Law’s dramatization of a 1968 interview Gregory gives at the legendary hungry i in San Francisco. By this point in his life and career, he is driven by activism far more than comedy. Actor John Carlin, in one of the many multiple roles he plays, ably portrays the puzzled, ostensibly liberal white interviewer, trying to make a connection, and trying to be supportive. But Gregory is having none of it. He deflects every question about what is or isn’t funny, and makes his points about racism and economic disparity, by referencing the Vietnam War and saying simply, “Train us to kill, and we will kill YOU.”

The scene gets to the heart of the dichotomy of Gregory’s career. Fighting for your life and your rights isn’t particularly funny, but when Dick Gregory is at his best, he takes his white-hot anger and spins it into brilliant comedy, without sacrificing depth or toadying to liberal white audiences. “Hell hath no fury like a scorned Northern liberal,” he quips, looking like a cross between a sage and a gleefully misbehaving kid. He names his most successful book Nigger, and tells his mother she can be proud, because every time anyone uses the word, it is free advertising.

Admiringly if reductively touted as a “Black Lenny Bruce,” Dick Gregory creates his own place in the show business universe by following the rules when it suits him, but mostly by breaking them. He gets the hoped-for call from The Tonight Show for his first appearance in front of a national audience, and agonizes before turning it down. The host Jack Paar himself calls, asking him to reconsider, and Gregory tells him the problem. Black comedians never get to sit on the couch and talk to the host after they perform. He doesn’t want to go on the show if he can’t sit on the couch. He gets his way—something that seems to happen a lot in his life.

The script jumps back and forth between various episodes in the ’˜60s and scenes in the 2010s and up to a month or so before he dies in August 2017. It offers Joe Morton a lot to sink his teeth into. I admire Morton very much, but I wonder if he is the right actor for this. The bad-boy performances that made Gregory a star take on a lecturing (even hectoring) quality when infused with Morton’s considerable gravitas. He is sometimes quite funny, and he does a very good, very funny impression of Dick Gregory doing Miles Davis that hints at a different sensibility, but mostly, we get heartfelt outrage.

I think some of the problem, is that inevitably, at the Wallis in Beverly Hills, a largely liberal, seemingly self-congratulatory audience agrees with every word. Taking on bigotry, trashing Trump, and taunting southerners has no feeling of daring or conflict here. Middle-aged lefty sensibilities are stroked—something Gregory himself would never do—and whites get to pat ourselves on the back for how progressive we are. The correlation between ’˜60s outrage and the Trumpian world in which we find ourselves now is real, but if we don’t confront ourselves about our own roles in this disaster, then this exploration of Dick Gregory’s message is meaningless.

Law’s script does try to make the leap—from preaching to the choir, to asking that choir to learn a few new songs. In Gregory’s first set at the Playboy Club in Chicago, the club audience is mostly drunk, racist Alabamans gathered for a convention. Carlin plays a generalized cracker, constantly calling Gregory a nigger. The comedian gets the upper hand, though, by encouraging the audience to stand up and say the word together, since he has a clause in his contract that every time someone in the audience says it, he gets an extra $50. We are forced to stand. And a middle-aged and elderly crowd of mostly good sports politely calls out, “Nigger,” with no relish, no energy, and no point. I commend the attempt at forging a deeper consciousness, but it falls flat. Canned laughter and recorded applause only underscores how odd the whole thing is, and instead of a leap, we get a stumble.

Director John Gould Rubin often blocks Morton awkwardly, as in numerous instances where the actor looks to an imaginary mirror downstage right and performs monologues that alternate between self-flagellations and pep-talks. They just don’t resonate the way they should. As I left the show, I felt sad and distracted. Some of that was the inescapable truth that America is still a place of racial intolerance—that Dick Gregory didn’t live to see all the changes he fought for.

The title comes from Gregory’s friend and compatriot Medgar Evers’ last words, “Turn me loose,” as he lay dying, murdered just for existing, for breathing. He knew he would die. Gregory thought he would too, but instead, tragically, his son was killed. “He died so I could live and support the movement.” Did he? Does the one thing have anything to do with the other? I don’t know. After the show, I went home and found YouTube footage of Dick Gregory. He was smart and hilarious. Rest in peace.

photos by Monique Carboni

Turn Me Loose

Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts

Bram Goldsmith Theater

9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd in Beverly Hills

ends on November 12, 2017

for tickets, call 310.746.4000 or visit The Wallis

for more info, visit Turn Me Loose the Play