BLINDING SON

I’m half Latino, half Eastern-European Jew, and I’m gay. But I know nothing of what it means to be African-American in a country founded on hating the color of your skin’”a country still defined, possessed even, by that hatred. I want to say that up front. No false equivalencies.

I’m half Latino, half Eastern-European Jew, and I’m gay. But I know nothing of what it means to be African-American in a country founded on hating the color of your skin’”a country still defined, possessed even, by that hatred. I want to say that up front. No false equivalencies.

That said, I will cop to feeling uncomfortably aware of being white as I let Native Son at Antaeus Theatre Company wash over me. I think perhaps that is as it should be. Playwright Nambi E. Kelley’s adaptation of Richard Wright’s novel hits with unrelenting force. The violence is agonizing. The casual racism is revealing. The flirtatious white debutante wants to go slumming, she wants to eat someplace where “your people” go’”refusing to acknowledge the mortal danger she unleashes on Bigger Thomas’”how it is her delusions about her own goodness that will lead to her death and to his doom.

I am nothing like Bigger Thomas. I am Bigger Thomas. I am white. I am not. My reactions to this vibrant piece of theater are confusing, and I want to unpack them a bit here. I grew up all over the world, and often felt puzzled by the beliefs of people I encountered in the multiple schools I briefly attended when back in America, where sexism and racism hid in plain sight.

There was the day on a schoolyard in rural Texas (of all places) when I had the confusing realization that just about every other person on the playground thought being male was somehow superior to being female. I knew they were wrong’”not in some proto-liberal enlightened way’”it was just that I had eyes. They were wrong. Then I started seeing the horrible damage the illusion wrought.

There was the day on a schoolyard in rural Texas (of all places) when I had the confusing realization that just about every other person on the playground thought being male was somehow superior to being female. I knew they were wrong’”not in some proto-liberal enlightened way’”it was just that I had eyes. They were wrong. Then I started seeing the horrible damage the illusion wrought.

I was also puzzled the first time I heard someone say some variation on not seeing color, being color blind, or not caring if a person is white, black, red, yellow, green, or purple. (Green? Like the sexy lady alien who tries to seduce Captain Kirk on a Star Trek episode? Or purple? Like’¦ I don’t know’¦ the bratty girl in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory?) The very fact that green or purple always figured into the phrase telegraphed that it was an unreal, illogical observation. They were wrong. I had eyes. Different colors exist. We see them. And our reactions to those differences have obvious, heartbreakingly real repercussions.

There’s also another bit of personal information I will share. My childhood was defined by violence. Sometimes it was there in fact. Mostly, it was a foreboding, an implied threat carried in on every breath, every heartbeat. I had recurring bad dreams of being punished, sometimes killed after being tried for murder. I was always guilty. When I was told that my nightmares weren’t real, I knew it was bullshit. They were true, though I couldn’t articulate how or why.

I don’t know how old I was the first time I read Richard Wright’s book Native Son. Possibly as young as eight or nine. I had a vague sense that it was a “classic” and that I was supposed to find it enlightening. What I remember is that I felt instantly at home in its nightmarish world of inescapable tragedy. Improbably, it was one of the first serious books I read that described the world I saw around me. Not literally. I had not experienced racism, just noticed it. I wasn’t alive in 1939. I had never been to Chicago. We were not poor. Yet reading it was like coming home’”both unbearable and revelatory.

It was also an example of how only by being very specific can one create something universal. If I cannot truly know what it is to be African-American, I can know precisely what it is to live in a nightmare. This is how Kelley’s stage adaptation succeeds and where it lives’”in the immersive, unstoppable reality of living in a world where nothing is ever fair, but suffering is inevitable.

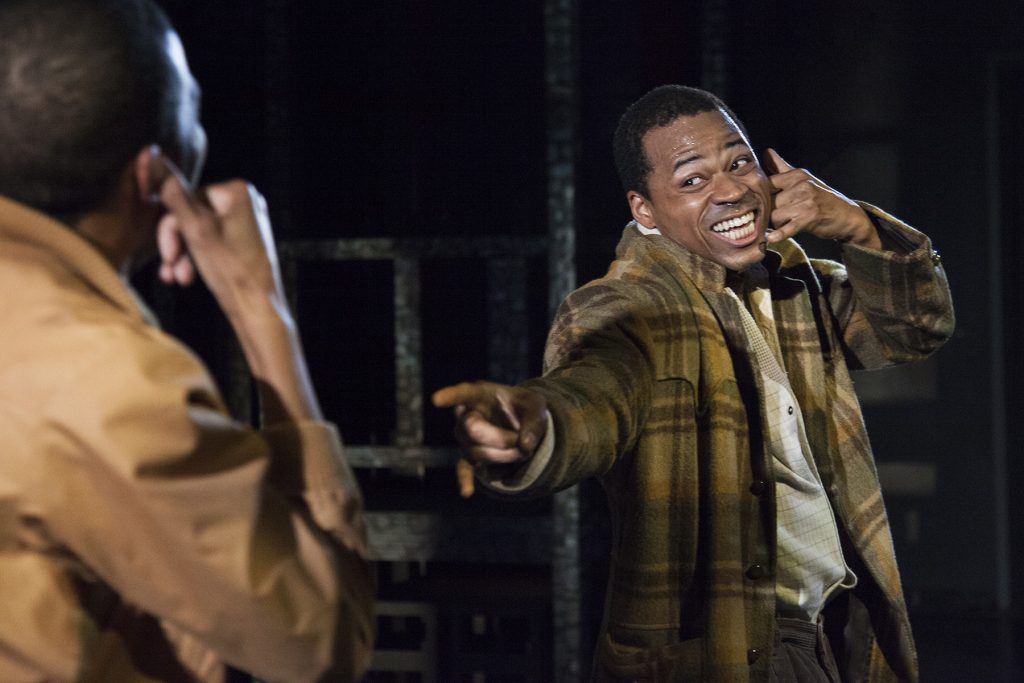

Kelley’s adaptation is both meticulous and expansive. Director Andi Chapman has assembled a phenomenal company of actors. Jon Chaffin is Bigger Thomas, a man who tries to flail himself out of the poverty of Chicago’s South Side, where he lives unhappily with his mother and sister (Victoria Platt and Mildred Marie Langford, who also plays his girlfriend). Noel Arthur is the Black Rat’”a twin projection of Bigger’s sub-conscious. Bigger takes a chauffeur job and finds himself in the white world of a wealthy blind woman (Gigi Bermingham), her careless, communist-leaning daughter (Ellis Greer), and her communist boyfriend (Matthew Grondin). The narrative takes us in and out of the past, present, and future’”all around one horrible, confused, fatal moment of fear and aggression.

The ensemble cast functions beautifully together, almost as a single entity, with Chaffin’s towering performance as Bigger acting as an engine, and Platt and Langford embodying the terror, grief, and loss of a set of circumstances that only seems random. If these events didn’t happen in this particular way, with these particular mistakes, they would have happened anyway’”as if a Greek tragedy, where Fate always will out. Resisting isn’t just pointless’”it infuriates the Gods, making their retribution all the worse for angering them.

Director Chapman brilliantly creates a cohesive universe. The fusion of sound, image, movement, and performance makes it hard to single out the source of individual creative contributions. Scenic designer Edward E. Haynes Jr., scenic artist Orlando De La Paz, lighting designer Andrew Schmedake, costume designer Wendell C. Carmichael, sound designer Jeff Gardner, video designer Adam R. Macias, production manager and technical director Cuyler Perry, properties designer Jacquelyn Gutierrez, fight choreographer Bo Foxworth, music arrangers Dr. Joi Carr and Mr. Addison Doby, and dramaturg Dylan Southard’”each is at the top of his, her, or their game.

If I am honest, I cannot say I enjoyed the evening. I don’t imagine Kelley or Chapman want me to. They are not after a casual or enjoyable experience. They mindfully use modern multimedia elements to plunge us into the past, then leave us dangling there, forcing us to see the present. And maybe that’s where that whole colorblind thing does come into play. Whites and people of color may have different feelings as we are buffeted about in the hurricane-force gales of Native Son, but in the end, we are all there together, twisting in the wind, wondering what hit us.

photos by Geoffrey Wade Photography

Native Son

Antaeus Theatre Company

Gindler Performing Arts Center, 110 East Broadway in Glendale

Thurs and Fri at 8; Sat at 2 & 8; Sun at 2

ends on June 3, 2018

for tickets, call 818.506.1983 or visit Antaeus