MOTHER COURAGE IN MOTOR CITY

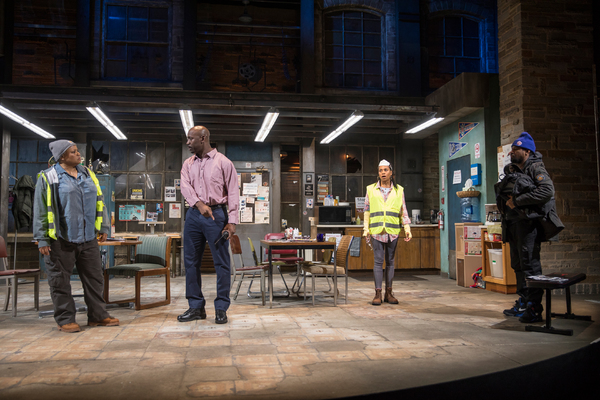

The marvel of scenic designer Rachel Meyers’ work greets you when you enter the theater at the Geffen Playhouse, and draws the audience into Skeleton Crew, the third and final installment in playwright Dominique Morisseau’s award-winning three-play cycle, The Detroit Project. Then Meyers’ set does an extraordinary thing: During onstage action it is a completely naturalistic breakroom in a Detroit steel stamping plant in 2008. In the scene breaks, though, it takes on a steam punk vibe, a kind of muscular whimsicality’”a highly effective contradiction in terms. Lighting designer Pablo Santiago and sound designer Everett Elton Bradman are a vital part of that transformation as well. This duality serves the narrative while also nudging us to consider broader, non-literal themes that are not directly spoken of in the text.

The story of four workers plays out against what can only be described as a war. Undeclared by some, overtly celebrated by others, there is a war on the African-American working class, and its impact is devastating; there are deadly consequences to one side; there are spiritually and emotionally deadening aftereffects to the other. This war has reached greater prominence in recent years, but it has been ebbing and flowing for centuries.

In 2008, the Motor City was bankrupt, and the financial crisis was in full swing. Blue collar workers faced a future that to many seemed not just uncertain, but nonexistent. The banks were rescued. The stock market rebounded. The poor were left to fight or perish. But in terms of war, this was not the beginning of anything. Even in the heyday of the automotive working class achieving a solid hold on job security and homeownership, there was a racial divide, with mostly white United Auto Workers having seniority. So the “good old days” were better, certainly, but they were hardly a paradise.

I don’t know if Morisseau intended any allusion or homage to Mother Courage and Her Children, but for me the connection kept creeping in, particularly as I’ve thought about her play in the days after seeing it. Skeleton Key is about the struggle for survival in what feels like an endless war, and the central character is a very flawed woman whose actions could result in destruction to the others or to herself at any moment. She is Faye, a 29-year veteran of the assembly line, who, it must be said, is much funnier and far more endearing than Brecht’s uber-survivor.

Faye uses secrets as currency, trading them or using them to quiet others when the need arises. She hides the fact from everyone that she is fighting for her life. Homeless and broke, she sleeps at the plant in the breakroom, hoping to get to her 30-year mark at the end of the year. The retirement package for working 29 years is considerably different than the one for working 30 years.

She is fast with quips. When hot flashes hit, and a coworker makes fun of her, she shoots back at him, “I got a heat you don’t know shit about,” and later, taunting him about the state of his car: ““It’s like an old dirty woman with an emphysema cough.” She tries to redirect concerns about what will happen if the plant closes, retorting, “If ’˜Ifs’ were fifths we’d all be drunk,” then “If ’˜Ifs’ were spliffs we’d all be high.” But when forced to admit her dire circumstances, she resists help. “Leave me to my own stink,” she half-demands and half-begs.

Faye and her coworkers are living on sand, as staff cuts lead to massive amounts of overtime, and rumors circulate of the plant’s imminent closing. Detroit is a city where “empty plants are a breeding ground for assembly line ghosts.” Reggie, Faye’s supervisor, tells her the rumor is a fact, but she must keep it a secret. They negotiate terms with one another about how and when to share the news. He wants her help in keeping a lid on it. Upper management is afraid that production will drop if news gets out, and Reggie worries his future prospects will be damaged if anything hampers hitting performance targets. Faye is the union rep and is fiercely protective of the workers, but she is also the surviving partner of Reggie’s late mother. Faye was responsible for Reggie getting hired. They are tied together, sharing an impossible burden, simultaneous allies and foes.

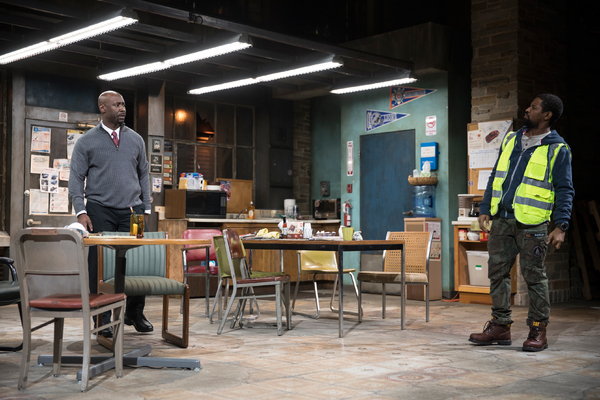

Reggie has made the conscious choice to please and reassure what we are given to believe is a largely white upper management group. His speech and dress reflect white notions of being the boss, but when he is angry, his speech is rougher around the edges, more revealing, and more impactful. That happens a few times in private conversations with Faye, but when he lets that mask slip in the second act and shows his boss the inner fury he keeps tamped down, he fears his whole future will crumble because of it. And you worry he might be right.

Shanita is a young pregnant woman with a fierce work ethic and a love for her job. Unlike the others, she does not make fun of Reggie’s many signs pinned to the breakroom bulletin boards: IF YOU ARE ON TIME YOU ARE LATE, WORK HARD AND BE PROUD OF WHAT YOU ACHIEVE, and multiple copies of NO SMOKING FAYE! “I love the way the line needs me,” she says, musing about the music of the machinery and the rhythm of the work. Later, as tensions rise, and she has her own meltdown, Faye cautions her, “Maybe you need to take a yoga class and calm yourself the fuck down.”

Dez is a younger man, hopeful about opening his own auto shop, but suspicious of management’s intentions and pragmatic about the violence that surrounds them all. He is sweet on Shanita, who shoots him down at every turn and refuses to answer any questions about her baby’s father. Dez tries to make her see that whoever the dad is and whatever he means to her, “Love don’t take you to the break room in tears every three days.” Later, finally, they have their moment, a kiss. She pulls away, freaked out. Her head is all over the place. “I know how you feel,” Dez says. She retorts, “Oh, are you pregnant and hormonal too?”

Fear of the future is threaded through everything, even as each character tries to make the most of the present. The plant bosses operate on a system of divide and conquer. They push people they want out to the limit, lay them off just before benefit schedules change, and treat them as easily replaceable machinery. When materials go missing, added security cameras and night watchmen are on the horizon.

Reggie is horrified and feels helpless when he learns that Faye is sleeping at the plant. Grief at her partner’s death led her to gambling at the casinos, a place where for a little while, she could make all the sad, ugly voices in her head subside. She lost her house. He wants her to move in with him and his family, but she hesitates. It isn’t just pride that stops her. Her entire identity is built on her ability to survive, to triumph over anything. She will never fully acknowledge her vulnerability, not to him, not to anyone, especially not to herself.

In a turn of events worthy of Lillian Hellmann, we learn that Dez carries a gun. It becomes a crucial element of the plot, propelling the story to an ending suffused with contradictory yet immensely satisfying mixed notes of hopefulness and despair.

The cast is brilliant. Caroline Stefanie Clay gives Faye a physical and visceral authenticity that is as heartfelt as it is unsentimental. She often exhibits a broad comedic physicality, but then creates moments of riveting stillness. You see her mind working, and you feel her terror and loss. DB Woodside embodies the dualities and contradictions within Reggie beautifully. He is patient, giving Reggie’s rage and confusion time to steep fully, then letting it explode. Woodside makes Reggie’s understanding and acceptance of Faye into a loving vision of what family can be, yet he also makes the character’s cluelessness about Faye’s circumstances somehow believable, if still kind of bewildering.

Kelly McCreary is endearing and slyly funny as Shanita. McCreary’s simplicity and emotional and physical fluidity never obscure the complexity of the character’s inner life. Amari Cheathom is equally effective. He makes Dez’s pursuit of Shanita into something charming and unexpectedly touching. His strength and versatility give Dez’s anger a real weight and sense of history.

Director Patricia McGregor keeps the energy focused and the movement flows gracefully. Skeleton Crew is a traditional, structured “well-made” or “talking” play, with little onstage action’”and I love that about it. Yet, from a physical standpoint, these kinds of plays can be tricky to direct. You need movement and physical activity that feels absolutely motivated. McGregor accomplishes that effortlessly, and then modulates the waves of humor, pathos, and existential carnage.

Dominique Morisseau sees layers within layers of human experience and cultural identity. The pull of opposing forces within and without are constantly in motion. Her genius is in making that awareness tangible and playable. The balance she creates may be delicate, but it is never fragile, and despair can turn heroic on a dime. At the end of Skeleton Crew, Faye makes a choice that is anything but conventional. She becomes a hero, albeit one whose heroic act occurs offstage.

Mother Courage is a character that Brecht insisted must remain in the prison she made for herself. He created her as an object lesson in the dehumanization of war. Faye seems destined to languish in a similar prison. Morisseau’s gift to her, and to us, is to allow Faye to transcend her suffering with an act of violent, reckless joy. Her tragedy is forgotten, at least for a while.

photos by Chris Whitaker

Skeleton Crew

Gil Cates Theater at the Geffen Playhouse

10866 Le Conte Avenue in Westwood

Tues-Fri at 8; Sat at 3 & 8; Sun at 2 & 7

ends on July 8, 2018

for tickets, call 310.208.5454 or visit Geffen Playhouse