CHILD MOLESTERS GET A PLAY

Some underdogs seem deeply deserving — which makes sympathy for devils a tricky proposition. Pulitzer-winning Bruce Norris has never shied away from upsetting the apple cart. Co-commissioned and co-produced with the National Theatre of Great Britain, Steppenwolf Theater’s latest provocation Downstate examines four child molesters in a group home. Norris exposes them as supposedly sick and marginalized “monsters,” disposable felons who will always be too close for comfort; and also as demons from our dark side who, yes again, will always be too close for comfort.

Happily, Downstate delivers a creditably balanced picture of the collective aftermath of crimes that aren’t unspeakable after all. Norris gives perpetrators and victims their fair say. So nobody in Steppenwolf’s Upstairs Theater can pretend to be innocent bystanders.

Happily, Downstate delivers a creditably balanced picture of the collective aftermath of crimes that aren’t unspeakable after all. Norris gives perpetrators and victims their fair say. So nobody in Steppenwolf’s Upstairs Theater can pretend to be innocent bystanders.

Shedding a harsh light on a situation most of us prefer shrouded in darkness, Norris’s 150-minute world premiere — ably abetted by director Pam MacKinnon — takes us inside a downstate half-way home for sex offenders operated by Lutheran Social Services of Illinois. Understandably unpopular with their “not in my backyard” neighbors, it’s seen broken windows and scrawled graffiti. A bat is kept at the door to repel invaders. For these ankle-monitored inmates, the exclusion area — schools and churches and the like — keeps expanding, which means they have to travel further and further for groceries (no alcohol, of course).

Norris’s not-necessarily representative characters embody extremes you’d expect in this surprisingly genteel-looking abode. From the criminals we get defensive denial, evasive extenuation, serviceable amnesia, and, in unguarded moments, unappeasable self-loathing. From their hard-boiled, tough-loving parole officer (Cecilia Noble), overworked with 47 charges, there’s only conditional empathy: She’s worn out with the criminals’ serial lies, paranoid blame-throwing, passive-aggression, and self-serving victimology.

And there’s one victim: Andy (Tim Hopper), a repeat accuser, here joined by his all-condemning wife (Matilda Ziegler). Andy was sodomized at 12 by Fred (Francis Guinan), a now paralyzed predator who escapes by playing Chopin. Andy incarnates an exhausting craving for payback, a demand for confession without absolution that verges on violence.

Fred, curiously, is almost grateful for the chance to come clean. Beset with ugly “trigger” memories, Andy, however, is obsessed with obtaining a declaration of accountability — technically a “reconciliation contract” — from Fred. It seems like righteous retaliation until our nuance-loving playwright raises the question of the reliability of recovered memory and the worth of a Javert-like persecution mania.

A second outcast is fast-talking, floridly religious Gio (Glenn Davis). A first time-offender who can game the system, he’s also a gay, street-hustling, motor-mouthed scam artist who perversely proclaims the exculpatory aspects of statutory rape.

A second outcast is fast-talking, floridly religious Gio (Glenn Davis). A first time-offender who can game the system, he’s also a gay, street-hustling, motor-mouthed scam artist who perversely proclaims the exculpatory aspects of statutory rape.

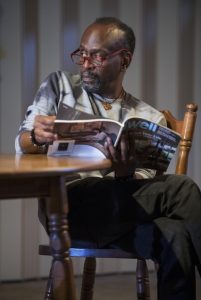

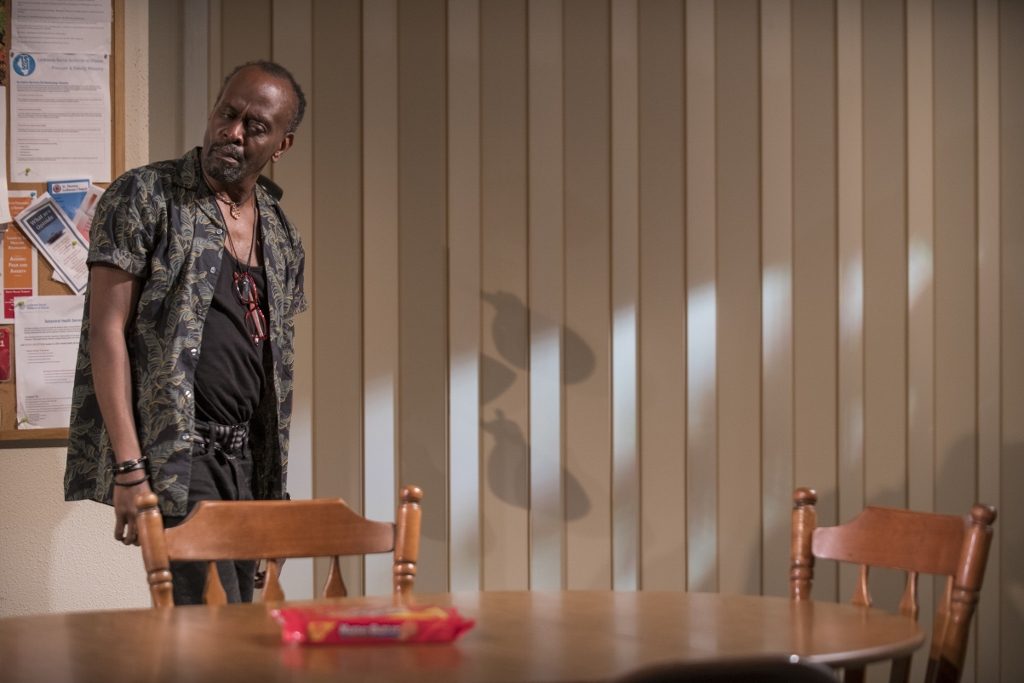

Also homosexual, Dee (K. Todd Freeman) is a litigious enabler whose second-act debate with Andy drives home all the play’s polarities. Dee argues the relativism of suffering. How can his haters say their pain is like death when they’ve clearly chosen to survive? Isn’t murder worse than rape? Besides, Dee still hears from his teenage prey, so how can he be altogether rotten? Finally, there’s Felix (Eddie Torres), a pathetic and lonely pedophile convicted of incest and aching to reunite with a dying sister who’s the only one left who loves him.

Trapped in their cycles of abuse, the four misfits run the gamut from regret to defiance, from minimizing their victims’ agonies to succumbing to shame. An irreducible reality remains: These guys have to live with themselves, a self-sentencing perhaps harsher than the hate they garner for not having killed themselves.

Norris’s feat is to keep them human when an audience prefers them a lot less. His case for tolerance, even forgiveness, is well worth hearing if not believing. Eight dogged actors ensure that a potentially bottom-feeding exercise in excess stays real and even true.

photos by Michael Brosilow

Downstate

Downstate

Steppenwolf Theatre Company

Steppenwolf’s Upstairs Theatre

1650 N Halsted St

ends on November 11, 2018

for tickets, call 312.335.1650

or visit Steppenwolf

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Oh, my. ENsure, not INSURE — please proof!!

Thanks for catching that in the last paragraph, Susan. It’s been updated.