CASTE ASIDE

Todd Solondz, one of the most profound filmmakers working today (Happiness, Welcome to the Dollhouse), begins his first play Emma and Max — which he also directs — with a scene right out of a Todd Solondz movie: An affluent white couple, Brooke and Jay, sit uncomfortable and tense in their living room opposite Brittany, their poor and exhausted black Barbadian nanny. “We just wanted to let you know. How happy. We’ve been. With you,” they tell her. “The children adore you’¦ You’re more than we could ever have hoped for.” Suddenly Brooke gets overwhelmed, runs into to the bathroom and vomits. This is “’¦like the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do in my life,” she tells her husband.

The two rejoin Brittany. They tell her they love her, tell her she’s better than family. Then Jay gives her an envelope. Three months’ severance. Now that the kids are getting older — Emma is three, Maxis is two — they’re replacing her with an au pair from Holland. When Brittany asks they assure her she’s done nothing wrong. “Sometimes the pieces of the puzzle don’t fit together,” Jay tells her. And when she wants to say goodbye to the kids the parents don’t let her. It’s only later, after Brittany leaves, that Brooke realizes she never took back Brittany’s keys to the house.

It’s a painful scene. We hate Jay and Brooke for stripping Brittany of the two most precious things in her life, her job and the children whom she clearly loves (a picture of them serves as her laptop background). But we also despise the pair for all the squirming and verbal contortions they perform to avoid saying what they mean, which is that they would rather a hip white culturally-European multilingual young woman serve as their children’s example than an ignorant funny-smelling black descendant of slaves from an impoverished island country.

Yet as we scowl at their actions and smirk at their words we are forced to admit that we agree with their thesis, at least in theory: We all want our children to have an all-access pass. We try to obfuscate our position with language, we insist on a politics of tolerance and inclusion, we talk about equality and believe what we’re saying. Yet there remains an unsolvable problem: It’s always better to be one thing than another. And currently it’s more desirable to be white and privileged than poor and black.

Yet as we scowl at their actions and smirk at their words we are forced to admit that we agree with their thesis, at least in theory: We all want our children to have an all-access pass. We try to obfuscate our position with language, we insist on a politics of tolerance and inclusion, we talk about equality and believe what we’re saying. Yet there remains an unsolvable problem: It’s always better to be one thing than another. And currently it’s more desirable to be white and privileged than poor and black.

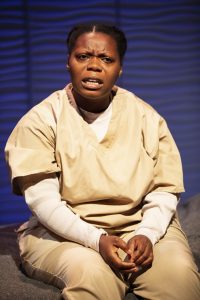

Brooke and Jay go from struggling with how to tell Brittany she’s fired to struggling with the deed itself. They struggle in their bedroom, they struggle poolside at a Barbados resort, in their hotel room, in a business-class airplane cabin. And it’s up to Brittany (a most convincing Zonya Love) to facilitate these scene changes. Watching her, exhausted and dejected, mustering what strength she has left to fold and unfold heavy accordion wall panels and pull out and push in unwieldy furniture and decorations on Julia Noulin-Mérat’s versatile set, we get a real sense of not only the labor she performs day-to-day but of how much it all takes out of her.

As Brooke and Jay try to justify their actions to themselves and to each other, wrestling with notions of race and privilege, they offer us insight into how they too have been insulted by life. Brooke (Ilana Becker), a beautiful blond 30-something who occasionally models, grew up ugly and fat it turns out. Classmates mercilessly taunted her as adults turned a blind eye. “I wish I’d been born black — then at least I could’ve shared the pain, the injustice of it all,” she confides to her husband. “But instead’¦who wants to be a member of the Ugly club?” It took Brooke lots of time, effort and procedures to look the way she does now. But she still remembers her childhood pain. In fact it’s almost as if she keeps it handy in case she needs to validate herself.

Jay (Matt Servitto) also suffered, though more subtly perhaps. His family had money and connections. He attended Princeton. Now he’s rich and successful, with a beautiful wife and two beautiful kids. It all came so easy to him. Yet he’s bitter. Is it because he was never well liked, not by friends nor by family? Is it because he knows he never could have gotten someone as beautiful as Brooke were it not for his status? Whatever the reasons, and in spite of all he has and has accomplished, Jay seems to carry inside him a malignant ball of resentment, dissatisfaction and victimhood: When he talks about the many people he’s had to fire in his life — all of whom deserved it, he insists — it’s as if he’s speaking from the position of the persecuted. As if him firing an employee is an injustice inflicted on him.

Then Brittany speaks; her story is one of youth and hope crushed by poverty, degradation, rape, death and murder.

All are guilty in Emma and Max yet no one is evil. They’re all people trapped in their bodies, in their histories, in their circumstances. At one point Brooke confesses to her husband that she feels guilty because she doesn’t feel more guilty about firing Brittany. Yet we can’t help but feel that this is not the whole truth. It’s almost as if Brooke can’t admit to herself that she indeed does feel badly because that would suggest that she’s done something wrong, which in turn would undermine the foundation of her basic beliefs and put her entire world view in jeopardy.

Mr. Solondz has tremendous empathy for his characters. In his world evil is not born of a desire to do bad or to hurt. It’s born of wanting to love and be loved, of desperation, of compulsion, of exhaustion, of the need for justice, of wanting to defend oneself and protect one’s loved ones. What is one to do when both action and inaction are impossible?

photos by Joan Marcus

Emma and Max

The Sam at The Flea Theater

20 Thomas Street (between Broadway & Church in Tribeca)

Wed-Mon at 7; Sat & Sun at 3 | ends on October 28, 2018EXTENDED to November 11, 2018

for tickets, call 212.352.3101 or visit The Flea