RAGING AGAINST THE DYING LIGHT

Elderly parents losing their independence is more significant demographically in America now than at any time in our history. Most still-living Greatest Generation parents of Baby Boomers are in their seventies to nineties or even early one-hundreds. After lifetimes of gritty independence, often forged during the Depression, they tend to find dependency on adult children abhorrent.

It strikes me that their insistence that they can do everything themselves is self-defeating and creates extra work for those they rely upon. When my in-laws moved from Florida to California in their eighties, they insisted on settling in Rancho Mirage instead of Los Angeles, so they wouldn’t be a burden to us. In practice this meant that when my husband’s mother couldn’t make an electronic device work, my husband had to drive 130 miles to turn the computer on. Which was, um, burdensome.

My father-in-law refused to use a walker. He didn’t want his grandchildren to see him as old or frail. It never computed for him that when his grandchildren saw him sprawled on the curb bleeding after falling it made him seem far older and frailer than if he just used the damned walker. Never mind the burden of time spent in emergency room visits that could have been easily avoided.

My father-in-law refused to use a walker. He didn’t want his grandchildren to see him as old or frail. It never computed for him that when his grandchildren saw him sprawled on the curb bleeding after falling it made him seem far older and frailer than if he just used the damned walker. Never mind the burden of time spent in emergency room visits that could have been easily avoided.

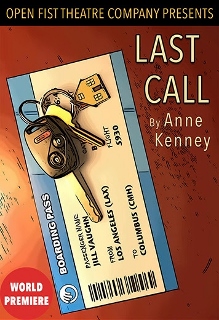

Yet I am not unmindful of how humiliating it must be to feel betrayed by one’s own mind and body and infantilized by one’s children. Particularly when bitter truths are closing in and no path seems viable. This is the reality facing the characters in Anne Kenney’s semi-autobiographical new play Last Call, now in its world premiere by the Open Fist Theatre Company at the Atwater Village Theatre.

Jill is a TV showrunner returned from LA to Ohio where her elderly dad, Walter, is losing his battle with liver cancer and her mother, Frances, is grappling with serious dementia. Jill is determined to move them into a senior care facility. Walter is determined that it will be over his dead body, perhaps literally.

Ricky, Jill’s younger brother, is a heroin addict in recovery, sleeping on a screened-in porch because Walter refuses to allow him to stay in the house (this after many thefts of family heirlooms and jewelry to buy drugs). A wild card shows up when Jade arrives. She is the 16-year-old mother to be of Ricky’s unborn child. They hooked up in rehab. That she is African-American is presented as if it might be an “issue” but there’s too much going on for that to matter to anyone, nor does the family seem overtly prejudiced.

There is a lot to admire in Ms. Kenney’s writing, not the least of which that the story feels handled in a modern way. She also makes Jill a monster in her television job — brave considering that some will assume she is writing about herself, since her extensive television credits extend all the way back to L.A. Law. (In my experience, no true monster ever recognizes herself or himself as such, so my guess is that Kenney is not the basis for Jill on that score.)

There are other ugly revelations. Walter was not an easy father to grow up with. Some of the decisions he is making for Frances are perhaps not as selfless or loving as they may seem at first glance. There’s a wonderful moment when Jill cops to  worrying about how Walter’s intentions might affect the life insurance payout. I loved that. It’s authentic in a way that belies the possibility of a tidy ending.

worrying about how Walter’s intentions might affect the life insurance payout. I loved that. It’s authentic in a way that belies the possibility of a tidy ending.

As the parents, Ben Martin and Lynn Milgrim are effective and endearing. Ms. Milgrim makes Frances’s growing anxiety both touching and frightening. We see who the woman was, and we see who she is becoming. Similarly, Mr. Martin fluidly conveys Walter’s past and present, both selves existing in the same haggard body. Laura Richardson does a fine job of unraveling Jill’s life, at first presenting the side the outside world sees, then exposing Jill’s current troubles and self-realizations.

The roles of Ricky and Jade are perhaps underwritten, and Art Hall and Bronte Scoggins don’t make as strong an impact as they might. The characters’ circumstances are interesting and potentially involving, but the text keeps things on the surface. Does the pair have a future? Common sense says it is unlikely, but it would be interesting to explore the possibilities or the limitations or both.

Stephanie Crothers shines in one scene as a care facility representative. At Walter’s constant carping she remarks on his sense of humor, and Ms. Crothers shows us the character’s entire life in one line, giving it a double, even triple meaning that reveals everything.

The family is at cross purposes and they don’t know how to genuinely communicate. That’s a good thing for drama. Kenney’s instinct seems to be to explore the full messiness of that family dynamic, yet for me it feels like she loses her nerve and starts pulling her punches toward the end. The certainties of the characters go basically unchallenged, and because of that, the depth of feeling for the audience doesn’t go as deep as it might.

On opening night, director Lane Allison gave a touching tribute to Anne Kenney, professing sincere appreciation for her work. I wonder if perhaps the differences in their ages and levels of experience subconsciously discouraged Ms. Allison from asking a few tough questions that could have helped Kenney hold to the courage of  her convictions. She certainly has the writing skill to go anywhere she chooses with the story and the characters — perhaps to a place that would preclude the nostalgic slide show ending that leaves an unsatisfying air of unearned resolution.

her convictions. She certainly has the writing skill to go anywhere she chooses with the story and the characters — perhaps to a place that would preclude the nostalgic slide show ending that leaves an unsatisfying air of unearned resolution.

It isn’t easy telling one’s own truth about the people we love. My father-in-law is dead, but I’m sure if my now 97-year-old mother-in-law were to read this, she would take issue with how I have characterized them. It feels ugly and unkind to have publicly taken them to task. Of course, my husband and I intend to bypass this issue entirely by employing live-in home health care workers as soon as we can afford it. We will become happily dependent before we need to. Unlike his parents, we’re entitled members of the Me Generation who have spent a lifetime hoping to be taken care of.

photos by Darrett Sanders and Lane Allison

Last Call

Open Fist Theatre Company

Atwater Village Theatre, 3269 Casitas Ave. in Atwater Village

Fri & Sat at 8; Sun at 2; Sun at 7:30 (Feb 17 only)

ends on February 23, 2019 EXTENDED to March 2, 2019

for tickets, call 323.882.6912 or visit Open Fist