SHATTERED GLASS

The Lodger symphony, Philip Glass’s brand new Symphony No. 12, is a work that the composer had discussed with David Bowie prior to the glam-rock king’s death (the two were friends and mutual admirers for many decades). Glass wanted to turn the 1979 album Lodger, a collaboration with Brian Eno and producer Tony Visconti, into a symphony, which would complete Glass’s reimagining of Bowie’s Berlin trilogy, following 1992’s Low symphony (Glass’s Symphony No. 1), and 1996’s Heroes symphony (Glass’s Fourth). Apparently after the commission to complete the symphony arrived from Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra, Southbank Centre, and Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra (where the world premiere played Jan. 10-13), Glass was no longer inspired by Bowie’s music and came up dry. But with bookings already in place, Glass took only the lyrics of seven of the ten songs (using all of them would have made the symphony over an hour long, Glass said), and turned them into’¦

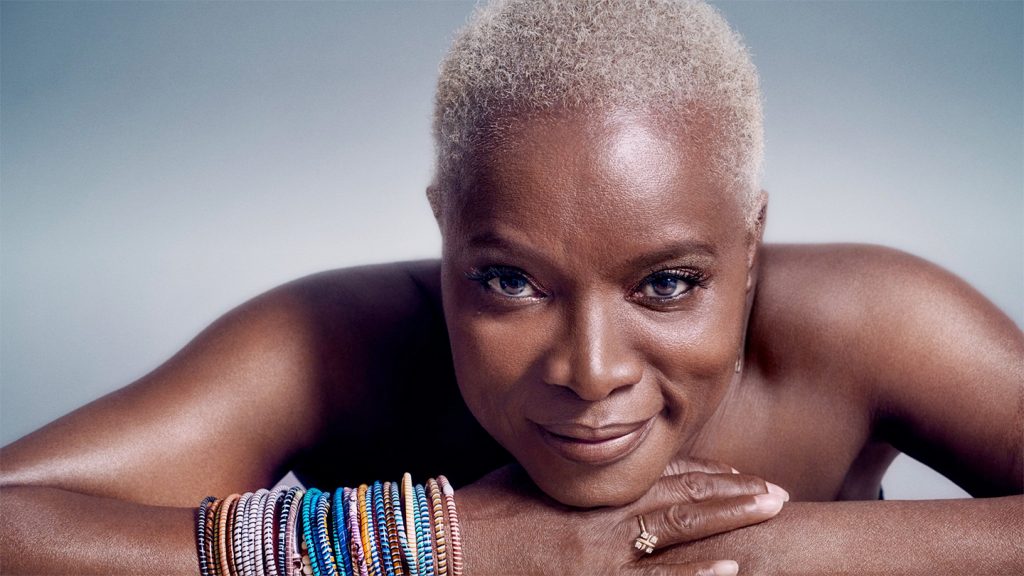

’¦a disaster. Mr. Glass may call it a “symphony,” but this is less an extended musical composition and more just a song cycle with no form or narrative. Painfully atonal, each song is indistinguishable from the other, and they do nothing to enhance the sometimes fascinating but often dense and impenetrable lyrics, sung by the one of our most individualistic and stunning vocalists, Africa’s Angélique Kidjo, whose Afro-pop, world-fusion pyrotechnics didn’t blend with the avant-garde music; still, it suited her better than an opera singer, who would have sounded silly (Kidjo had lyrics in front of her on a music stand, but not the music).

These songs are as far from most Glass operas that I’ve heard. There certainly contain the typical Glassian features in which the smallest change has the greatest significance, with minimalistic, mesmerizing, mantra-like arrangements of notes that delicately move away from one another, but to me it sounded like Danny Elfman and Steve Reich threw up on a wounded calliope.

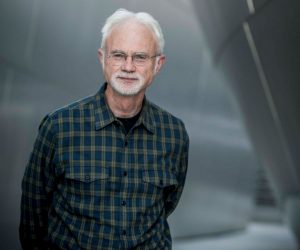

Also on the program was John Adams’ Grand Pianola Music, conducted by the composer. Requiring a much smaller orchestra — 21 pieces with no strings, 2 pianos, and 3 vocalists — this 1982 work sounds something like a series of futuristic musical experiments — like a soundtrack from a ride in EPCOT’s Future World (which coincidentally opened in 1982). With his gloriously emphatic leadership, Adams can do no more to this piece than anyone else, because it’s problematic to begin with. What it does have going for it is some fun moments. After slight palpitations from the pianos (the amazing Marc-André Hamelin and Orli Shaham), and some high, rolling pinging by the woodwinds, the New Age factor kicks in (1982, right?) that can be attractive but never weighty or insightful. Sopranos (Zanaida Robles, Holly Sedillos, Kristen Toedtman) enter with syllabic harmony above the players, and while the women got every “dit-dot, na-na, la-la” down pat, and the brass comes in trying to add gravitas, the loveliness always gives way to some kind of forward momentum that doesn’t break through to something exciting. So, while there are some really great moments in Grand Pianola Music, largely it’s rather ineffective. It sounds compulsory and hackneyed.

Also on the program was John Adams’ Grand Pianola Music, conducted by the composer. Requiring a much smaller orchestra — 21 pieces with no strings, 2 pianos, and 3 vocalists — this 1982 work sounds something like a series of futuristic musical experiments — like a soundtrack from a ride in EPCOT’s Future World (which coincidentally opened in 1982). With his gloriously emphatic leadership, Adams can do no more to this piece than anyone else, because it’s problematic to begin with. What it does have going for it is some fun moments. After slight palpitations from the pianos (the amazing Marc-André Hamelin and Orli Shaham), and some high, rolling pinging by the woodwinds, the New Age factor kicks in (1982, right?) that can be attractive but never weighty or insightful. Sopranos (Zanaida Robles, Holly Sedillos, Kristen Toedtman) enter with syllabic harmony above the players, and while the women got every “dit-dot, na-na, la-la” down pat, and the brass comes in trying to add gravitas, the loveliness always gives way to some kind of forward momentum that doesn’t break through to something exciting. So, while there are some really great moments in Grand Pianola Music, largely it’s rather ineffective. It sounds compulsory and hackneyed.

The most successful piece of the night was the opening by a young female composer, Gabriella Smith. Tumblebird Contrails (2014) is a tone poem musique concrete, in which sounds that we hear are created by manipulated instruments. The inspirational soundscape for Ms. Smith was a day near the beach. This grand and successful experiment in instrumentation has strings sounding like distant seagulls, bass like faraway airplanes, and other sounds which are up for interpretation: was that a bloated walrus? water skipping over pebbles? The drums — snare, bass and kettle — use sticks, mallets and brushes, and the strings operate with different techniques at the same time, so while occasionally cacophonous the work was never pretentious, the steady beat flowing and ebbing like waves. Perhaps the reason that it succeeded so well was the 12-minute length. Any more than that would become torturous. And we would get plenty of that in the second half of the program from Mr. Glass.

Adams & Glass

LA Philharmonic

Walt Disney Concert Hall

ends on January 13, 2019

for tickets, call 323.850.2000 or visit LA Phil

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

Glad to be on an aisle, we walked out 3 songs into the Glass piece… just wretched.

We were in the center of a row, so we had to endure this lemon squeezing acidic juice on us for what felt like an eternity.

Having endured the European premiere of this symphony last night, I was curious to see what the reviewers had said. Initially I came across a eulogising review in the Los Angeles Times – a million miles from reflecting our experience. Your review is far closer to how we felt, and clearly there were others in the audience who felt the same because there was a noticeable stream of departures which started after the first 20 minutes or so.