RUNNING ON FULL

After producer Sophina Brown’s celebrated production last year of King Headly II — one of ten dramas of the late August Wilson’s 2oth-century chronicle The Pittsburgh Cycle — she staked a claim to produce the entire oeuvre. Her promise is Los Angeles’s gift. Opening last weekend at the Matrix Theatre, Two Trains Running, a 1992 Pulitzer-Prize nominated time capsule, still entangles us today with director Michele Shay’s riveting production. As much a warning as a matter of memory, the inequity that Selma couldn’t end and that Ferguson continued is center stage for nearly three highly rewarding hours.

Shay’s smoking staging not only reprises Wilson’s textured talkfest, it proves Wilson’s constancy to America’s contradictions. Seen from the sidelines, the civil rights movement comes down to conversations here, history as it happens. The people aren’t the plot in this confluence of gritty characters, they’re the entire play. Two Trains Running exists not for any high-risk conflicts it presents or even its snapshot-sharp details about the Hill District of Pittsburgh circa 1969, mired in need and convulsed with change. It’s here to let seven souls speak. And listen you must.

This is eavesdropping raised to a sweet, if a bit overlong, science (most of Wilson’s plays could use a little trim). The magnificent seven talk themselves into existence, vibrantly and organically. John Iacovelli’s realistic design sets us in Memphis Lee’s decaying diner with its defective jukebox (vibrant sound by Jeff Gardner, whose 1969 song selections should have their own CD), where regulars gab and a new arrival shakes things up. Two very different occasions provide past and future backdrops: Looking back, there’s the imminent funeral and burial of Prophet Samuel, a spiritual mentor more reverenced than heeded. Looking ahead, a Malcolm X birthday rally is scheduled to demand jobs and justice?

Closer to home, Memphis (Montae Russell) wants not only to avoid Pittsburgh’s eminent-domain condemnation of his place but to get $25,000 for the site and property. Will he let the city take it over or sell it to funeral parlor owner West (remarkably sympathetic Alex Morris), a hard-fisted local mogul? Or will Memphis, as the 322-year-old living ancestor Aunt Esther suggests, return to his Dixie roots, driving a Cadillac in slow-motion revenge against the crackers who sent him north?

That’s about as much as hangs in the balance in this backwater where bad luck and hard times last longer than anyone should endure. The “action” is storytelling that passes for survival. Mr. Russell works wonders to convey Memphis’s stubborn streaks, while Nija Okoro brings razor-sharp vulnerability and stealth to Risa, a quietly intense waitress who distrusts the violence in the men around her; the scars on her legs from cutting are reminders that she wants to be prized for herself, not her parts.

Instantly intending to marry her, ex-con Sterling (Dorian Missick, a tiger in a cage) is a young blood impatient for wealth and ready to blame his failure on a mean world. His incipient black nationalism irritates neighborhood sage Holloway (stunning Adolphus Ward), a veteran defeatist with folk wisdom to spare: Giving up on his own dreams, he urges Sterling to see Aunt Esther to change his fate. (Her answer, as usual, is for hope seekers to throw a $20 bill in the Monongahela River and wait for better days.)

Sterling would rather get rich quick playing the local lottery, embodied by Wolf (Jon Chaffin), a numbers runner who trades in hot guns as a sideline: He likes his women in the daytime because he can’t trust people enough to close his eyes. But, just as in life, the numbers payoff can’t be relied on either: It gets “cut” if too many players threaten to win the same three numbers. Chaffin, stepping in for Terrell Tilford, proves that you should never doubt an understudy — he was so convincing that I wanted to buy into the numbers game myself.

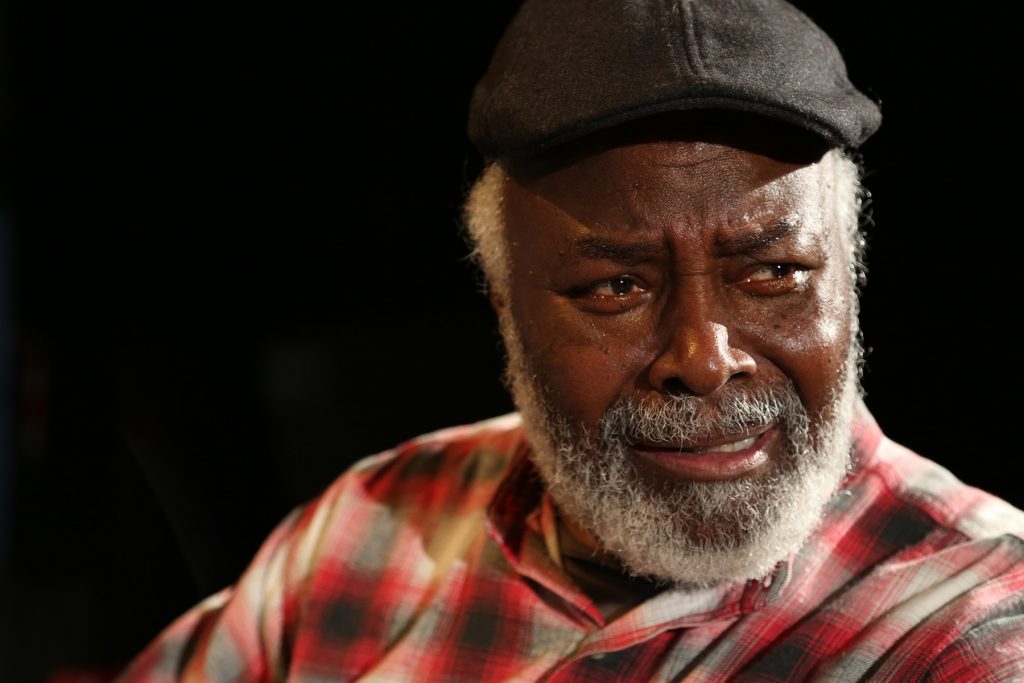

Finally, there’s misfit Hambone (childlike and heartbreaking Ellis E. Williams), a mentally disturbed house painter rampaging with rage as he demands a ham for services rendered to a white rip-off artist (instead of the lousy chicken he got as payment). The characters’ reactions to Hambone provide a litmus test for how much change they can handle and how much hope they can harbor. Coping with poverty takes many forms: Sometimes it’s better just to believe, like Sterling, that the moon is getting too close to earth and our sorrows will soon be superfluous.

Along the way Shay’s superb septet regale us with neighborhood gossip teeming with telling anecdotes (not for once does the word “nigger” offend — it’s purely dialectical and used often) that make the Hill District as palpable as Oxford, Mississippi, where Faulkner set 14 novels. Debates erupt about how much responsibility people can assume if individual merit doesn’t matter and group action backfires. The shared experience of these voluble dreamers is even greater than their showcase soliloquies. Wilson remains unsurpassed at catching people in the act of anything with such poetic authenticity that it’s no act at all. He makes theater honest all over again.

photos by Tiffany Judkins

Two Trains Running

Matrix Theatre, 7657 Melrose Ave.

Thurs–Sat at 8; Sat & Sun at 2

ends on March 3, 2019

for tickets, call 855.326.9945 or Trains