PRETTY HURTS SO GOOD

The title of Tori Sampson’s If Pretty Hurts Ugly Must Be a Muhfucka is a sly retort to Beyoncé’s 2013 song “Pretty Hurts,” both of which lament the negative impacts of rigid, Eurocentric beauty standards on young women — especially young black women. Beyoncé is not the only iconically beautiful woman of color whose spectre hangs over the play: there are references to Aladdin’s Princess Jasmine, Zoe Saldana in Center Stage, and, in Sampson’s program note, Brandy’s role as the titular princess in the 1997 TV remake of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella. For twenty- and thirty-something women who came of age at the turn of the millennium and began a search to see themselves reflected in whitewashed mass media, these characters are both an empowering and destructive force. In order for a woman to be considered beautiful, other women must be found lacking in comparison.

If Pretty Hurts is a powerful examination of these contradictions. Sampson writes, “I wanted to use a folktale in a contemporary way to interrogate why, for instance, Viola Davis isn’t ’˜classically beautiful’ and why the country had such a hard time aesthetically with Michelle Obama. The first time I saw her I was awestruck; this was a beautiful black woman whose hair is like mine; her skin is like mine; and to see the attributes of her that I really admired, to see the media tear them down, really troubles me. I wanted to examine the impact of colonization on Black beauty, and to ask what is Black beauty, in a way that speaks specifically to Black women.”

Sampson transposes a Nigerian folktale to the fantasy village of Affreakah-Amirrorikah, visualizedas a surreal set by Louisa Thompson at Playwrights Horizon; it consists of a giant round platform surrounded by translucent plastic and hundreds of round light bulbs. The beautiful Akim (NÃkẹ Uche Kadri), secluded from society by her overprotective parents (Maechi Aharanwa and Jason Bowen), is trailed by three jealous classmates, Massassi (Antoinette Crowe-Legacy), Kaya (Phumzile Sitole), and Adama (Mirirai Sithole), who are constantly made aware of their failures to measure up to her.

All four, giving well-matched and strong performances, are given compelling monologues which allow them to reflect on their place in the beauty hierarchy: Akim ponders the random nature of its distribution (“A rich person can be born a scare and a poor person a gem’¦ Beauty is neither your accomplishment or your failure”); Massassi resents the way her curves have led to her over-sexualization since childhood; Kaya self-deprecates as “the smart one” and “a solid six”; and Adama wishes to be free of the baggage of embodiment altogether (“My interior is in constant conflict with my exterior”). Notably, Sampson gives them all the same description in her script: “Beautiful girl. 17 years life.” She expands in the casting notes: “Grant audiences the gift of basking in beauty beyond Eurocentric measurements. Akim should not have a lighter skin tone than Massassi. Nobody needs to be tall, skinny, have straight teeth, clear skin, long hair etc. BE beauty in all your glory.”

The crux of the play’s action comes when Massassi, driven mad with jealousy when local heartthrob Kasim (Leland Fowler) turns his attentions away from her and toward Akim, plots with the others to lead Akim to her death via drowning in the river. However, as in many fairy tales and folktales, death is not the end: in one of the most transcendent sequences, Akim and Adama (who allows herself to drown in the struggle as well) are cleansed of their differences deep underwater, joined by the rest of the cast, cloaked in identical outfits and masks. Carla R. Stewart, as the singing voice of the river, blows the roof off the theater as she accompanies their silent movements (choreographed by Raja Feather Kelly) with a song written by Sampson.

Sampson’s text has many clever devices in it, ably brought to life by director Leah C. Gardner, including a one-man chorus (Rotimi Agbabiaka) who serves as the personification of Akim’s mobile phone. However, her best and most surprising trick comes at the end, when we realize that the true protagonist is not Akim after all: it’s Massassi. Sampson’s bait-and-switch forces us to question our own assumptions of who we’re supposed to root for, assumptions ingrained by hundreds of years of effortlessly, guilelessly beautiful heroines whose looks affirm their virtues. Sampson offers a more complex and painful view, but ultimately infused with a glimmer of hope as well.

photos by Joan Marcus

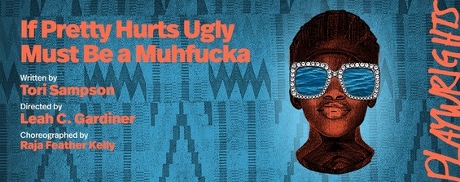

If Pretty Hurts Ugly Must Be a Muhfucka

Playwrights Horizons

416 W 42nd St (Mainstage Theater

Tues & Wed at 7; Thurs-Sat at 8; Sat at 2:30; Sun at 2:30 & 7:30

ends on March 31, 2019 EXTENDED to April 5, 2019

for tickets, call 212.279.4200 or visit Playwrights Horizon