A SHIP THAT REMAINS DOCKED

Sting’s musical The Last Ship has been in a shakedown cruise since it opened in Chicago six years ago. Based on last night’s star-studded opening night at the Ahmanson in Los Angeles, this retooled version sadly remains docked. Sure, it’s got a decent new book that jettisons jetsam from the Broadway libretto, but too much flat flotsam remains; what we have is a musical far more sincere than convincing. You can rearrange deck chairs till the crows come home, but the main issue anchoring the show down is the context.

Since the ’80s, when Margaret Thatcher polarized with her hectoring and largely successful attempts to dismantle the hard-won gains of generations of working people, fervent artistic tributes to blue-collar Brits have popped up like popovers. These salutes to stolid survival honor underdog heroes fighting hard times and mean bosses. Invariably, these stoic characters take a dramatic stand, however doomed or demented — think Billy Elliott, The Full Monty, Brassed Off, Kinky Boots, The World’s End, and Calendar Girls to cite just a few. For the reiteration of this Broadway-flop reclamation musical, superstar Sting still reaches into his childhood near Newcastle-upon-Tyne to recreate a lost world: the endangered Swan Hunter shipyard in the northeast English port of Wallsend. Here ships would grow “until they blotted out the sun.” (Or until the Koreans built cheaper ones and the workers became redundant.)

To raise the mizzen mast on flagging sails, er, sales, Sting joined the Broadway company for a bit, and now he’s back for the L.A. production, the first act of which is fairly dull and disengaging, causing quite a few patrons to disembark before the second act, which fares much better than the first (although Act II begins with a group of ladies singing directly to audience members with the house lights up as if we were in a pub — what is this ship?!).

The whole affair sort of feels like a muddled masterwork where symbolism trumps probability. It wants to be a dramatic play with music, but it still has too much that feels like humorless working-class underdog musicals, such as Hands on a Hardbody, when it wants to be Once. (Is it too late to call in Once‘s writer Enda Walsh to doctor the original book by John Logan and Brian Yorkey?)

The whole affair sort of feels like a muddled masterwork where symbolism trumps probability. It wants to be a dramatic play with music, but it still has too much that feels like humorless working-class underdog musicals, such as Hands on a Hardbody, when it wants to be Once. (Is it too late to call in Once‘s writer Enda Walsh to doctor the original book by John Logan and Brian Yorkey?)

It looks good (the video design by 59 Productions brilliantly opens up the stationary set), and has a motor capable of reaching far destinations, but doesn’t have the fuel it needs to get out of dock. In order to do that, the creators need to dig deeper somehow. The updated book by Lorne Campbell does have some truly terrific dialogue, and the British actors are superb (well, Sting could drop a few mannerisms), but many roles still feel like stock characters when they should come off like the regular folk in Come from Away, and Campbell’s direction is often so static that I longed for original helmsman Joe Mantello.

The Last Ship views the proletariat struggle through the eyes of prodigal son Gideon Fletcher (charismatic Oliver Savile), a runaway dreamer who became a sailor rather than, as his harsh dad desired, a shipbuilder. Returning to Wallsend after fifteen years of literal drifting, he finds a lot of unfinished business: A shipyard which can’t be salvaged and will soon be scrap; unprocessed memories of his dead father; friendships cut short by Gideon’s ill-considered escape; and, above all, his yearning for Meg Dawson (beautiful belter Frances McNamee).

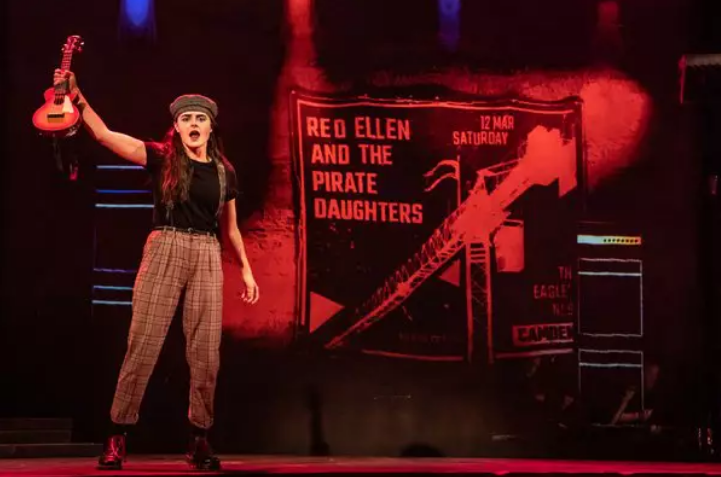

But now Meg has a brash, disillusioned, rebellious teenage daughter, Ellen, who just wants to run away and start a band in London. (Sophie Reid does her best in this most stock character of roles). The child that Gideon never knew he left behind bonds with her dad in the lovely waltzing number “When the Pugilist Learned to Dance.”

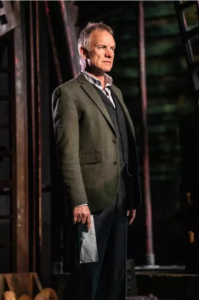

The other story involves valiant foreman Jackie White (Sting), who we know — really, no spoiler here — is dying from his first cough. The bleak future’s undertow creates some lovely scenes between Jackie and his wife Peggy (a stalwart and earnest Jackie Morrison). Jackie, refusing to face his death, and Gideon and the townsfolk, refusing to face the death of a way of life, are inspired by a scheme to storm the shuttered shipyard and steal the almost completed ship, hit the high seas, and proclaim their craft to the world. Besides reigniting his passion for Meg, Gideon’s semi-redemptive return has him join his people and commandeer the ship.

It seems a pipe dream out of Eugene O’Neill — a community’s crack-brained idea to illegally take a ship without a company or a buyer, then sail it anywhere until — who knows? — imminent impoverishment makes them scuttle it. Unlike Billy Elliot’s ballet, The Full Monty‘s Full Monty or Calendar Girls’ geriatric calendar, this desperate measure is the kind of empty gesture that’s supposedly too romantic to seem contrived. It would be so much easier to embrace this fantasy if we weren’t subjected to familiar but not engrossing types who make Wallsend a rather generic seaside storybook in which the melodrama gets old.

Happily, the overlong story also fuels anthems magnificently belted out by the shipwrights, riveters, welders, iron-makers, keel-haulers, and their faithful females. Sting’s serviceable songs, most of them original to the show, range from the soaring opening number to the self-descriptive romp “When We Danced” to the women’s arch chorus of “Mrs. Dees’ Rant.” Committed to making this a conventional musical and not a live jukebox, an un-waspish Sting delivers no generic rock score but a pretty pastiche of waltzes, two-steps, and even a raunchy rumba. The result is a supple mix of artful ditties (“August Winds,” “So to Speak”), bittersweet numbers “(“We’ve Got Nowt Else”), and winsome ballads (Gideon’s hopeful “And Yet” and the winning trio “Dead Man’s Boots”). Except for large group numbers, or when Richard John’s awesome onstage band is overmiked, the lyrics are as comprehensible as they are supple, smart and well-targeted — even as they are sorely lacking in wit. It’s OK that the lyrics don’t reach out and grab you (for a musical), but the book has to, and it just doesn’t. Worse yet, the book is such that songs don’t feel organic to the characters singing them.

The perfectly-cast leads and impeccable ensemble honor the driven dreams that few but Sting capture so completely. Even if it’s a misfire, I want this show to succeed. I wonder. With more ballast and less cargo, this musical may one day float.

photos by Matthew Murphy

The Last Ship

presented by Center Theatre Group

Music Center’s Ahmanson Theatre, 135 N. Grand Ave.

ends on February 16, 2020

for tickets, call 213.972.4400 or visit CTG

tour continues into 2020

for dates, cities, and tickets, visit The Last Ship