GLORY GLORY GLORIA

I don’t know if Branden Jacobs-Jenkins has ever worked in a Manhattan publishing house but he sure knows his way about the workplace. In Gloria, he paints an extraordinary portrait of the workings of an office whose conflicts revolve around some writers with their own agendas, a sense of emotional intensity on their part, combined with a certain waywardness about the work itself. They are apt to take breaks to go to Starbucks as often as possible rather than dedicate themselves to the kind of work which would define them. But they are defined, in their own words, by the brilliantly blistering monologues the playwright has written for them. Buoyed both by a unifying sense of reality and a cockeyed sense of abstraction, which is the personal technique of its author, whose plays include the breathtakingly original Neighbors and An Octoroon, the first act of Gloria moves with a steady pace, skewering everyone and everything within its reach, without losing a sense of comic breadth and, at the same time, a serious kind of logic and wisdom. You might call it a new kind of theater of the ridiculous. You immerse yourself in the naturalism of the setting and its people, while seeing through all the human absurdity, and still come unprepared for the menace that lies just below the surface and which finally reveals itself just before the curtain comes down on the first act.

I don’t know if Branden Jacobs-Jenkins has ever worked in a Manhattan publishing house but he sure knows his way about the workplace. In Gloria, he paints an extraordinary portrait of the workings of an office whose conflicts revolve around some writers with their own agendas, a sense of emotional intensity on their part, combined with a certain waywardness about the work itself. They are apt to take breaks to go to Starbucks as often as possible rather than dedicate themselves to the kind of work which would define them. But they are defined, in their own words, by the brilliantly blistering monologues the playwright has written for them. Buoyed both by a unifying sense of reality and a cockeyed sense of abstraction, which is the personal technique of its author, whose plays include the breathtakingly original Neighbors and An Octoroon, the first act of Gloria moves with a steady pace, skewering everyone and everything within its reach, without losing a sense of comic breadth and, at the same time, a serious kind of logic and wisdom. You might call it a new kind of theater of the ridiculous. You immerse yourself in the naturalism of the setting and its people, while seeing through all the human absurdity, and still come unprepared for the menace that lies just below the surface and which finally reveals itself just before the curtain comes down on the first act.

The real beauty of Jacobs-Jenkins’ play is the second act, which you come back after intermission expecting questions to be answered, only to find that the playwright has something else on his mind, something more layered and complex. The shift in tone presents some directorial challenges which are not completely attended to in this production, but which in no way affect our fascination with its twists and turns. Eric Ting, the director, does such a stunning job with the first act, setting into motion every nuance provided by the play itself and giving every actor, all of whom are excellent, room to display their every quirk, that one might think that, when things don’t fully come together, the fault is with the play, but my guess is that the play holds more depth and substance than Ting seems willing to explore. In short, the play sticks to you long after you’ve left the theater, even if you are left somewhat unsettled by its stubborn refusal to be clear, when what the audience probably wants is to be assured of its conclusions rather than to be left disturbed. In short, perhaps we needed to be more, not less, disturbed.

The real beauty of Jacobs-Jenkins’ play is the second act, which you come back after intermission expecting questions to be answered, only to find that the playwright has something else on his mind, something more layered and complex. The shift in tone presents some directorial challenges which are not completely attended to in this production, but which in no way affect our fascination with its twists and turns. Eric Ting, the director, does such a stunning job with the first act, setting into motion every nuance provided by the play itself and giving every actor, all of whom are excellent, room to display their every quirk, that one might think that, when things don’t fully come together, the fault is with the play, but my guess is that the play holds more depth and substance than Ting seems willing to explore. In short, the play sticks to you long after you’ve left the theater, even if you are left somewhat unsettled by its stubborn refusal to be clear, when what the audience probably wants is to be assured of its conclusions rather than to be left disturbed. In short, perhaps we needed to be more, not less, disturbed.

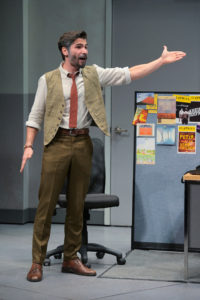

This production owes a great deal to Lawrence E. Moten III’s set designs, particularly that first act office, to Wen-Ling Liao’s superb lighting, and to the costumes which Christine Crook clearly fashioned to give her actors their rightful sense of character. The performances are uniformly solid, but Jeremy Kahn, Martha Brigham, and Melanie Arii Mah stand out, until the second act when Lauren English, whose character comes to fruition, takes charge in a remarkable revelation of who she is, heard but never seen in the first act, but always a powerfully enigmatic creation. If there is one problem, it is that some of the actors are required to play multiple roles and don’t always make the second or third character that different from the way they have been seen in the first character they portray. Matt Monaco, central to the action, is brilliant in Act I, but somehow missing in action in the play’s relevant conclusion. He is almost sure to grow in the role with time.

In all, this is what theater should be: unique, sharp, funny, adventurous. Its production flaws disappear in the midst of so much creative bounty. And Branden Jacobs-Jenkins continues to be one of contemporary theater’s most valuable assets.

photos by Kevin Berne

Gloria

American Conservatory Theatre

A.C.T.’s Strand Theater, 1127 Market St

ends on April 12, 2020

for tickets, call 415.749.2228 or visit A.C.T.