PIONEERS OF QUEER CINEMA

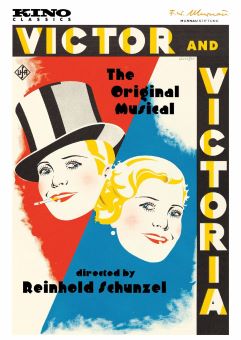

*********************** Viktor und Viktoria

Viktor und Viktoria

UFA Pictures | in German with English subtitles | Germany | 1933

directed by Reinhold Schünzel

Long before Julie Andrews dropped an octave for Victor/Victoria, there was Viktor und Viktoria, the German movie that started it all in 1933. From this evolved a French version, George et Georgette, shot simultaneously by the same director, Reinhold Schünzel; an English adaptation in 1935, First a Girl, starring Jessie Matthews; another German version Viktor und Viktoria (1957) starring the redoubtable Annie Cordy; and the celebrated Blake Edwards musical reworking with Andrews in 1982.

The long life of this theme would be hard to justify were the premise not as amusing today as it was in 1933. Viktoria (Renate Müller), unable to secure work in the music halls, joins forces with a down-and-out ham actor (Hermann Thimig) and between them, they evolve an act where Viktoria pretends to be a man performing in drag. Victoria becomes the toast of the international stage, but complications ensue when her professional gender-bending leads to personal chaos.

Müller and Thimig are perfect as the battling professional duo while the suave Anton Walbrook (billed here as Adolf Wohlbrück) is Viktoria’s love interest. Unlike the Edwards version, there is no hint of homosexuality in the original, either implied or suspected. Walbrook is in on the scheme from the start and plays it out by forcing such masculine exercises on Viktoria as a barbershop shave and introducing “him” to potential female suitors. The comedy arises from Müller’s reluctance to continue the masquerade versus the extremely desirable income.

A remarkable example of the late Weimar freedom of thought, humor and expression, this is slick, entertaining filmmaking. Director Schünzel’s camera is always fluid, panning from character to character, sometimes traveling for long walk-and-talk shots which eventually focus on the essentials of a scene. He borrows unashamedly from such as the ultrasophisticated 1932 Lubitsch movie One Hour with You, and the geometric marvels of Busby Berkeley’s choreography, but this appropriation in no way diminishes the joy of Schünzel’s use of these elements. As in One Hour with You, actors occasionally lapse seamlessly into rhyming couplets which segue just as seamlessly into musical numbers.

It’s interesting to note that the Austrian actor Anton Walbrook, a homosexual, was already an established and popular leading man in German film at this time. When the Nazi rise to power became inevitable in 1936, he relocated to the United Kingdom where he became well-known as a major leading man in film and theatre until his death in 1967.

If I had to revoke my suspension of disbelief, my sole quibble about Viktoria would be the same as for Blake Edwards’ Victoria: for all of the masculine swagger, the hair smoothing, the lowered vocal tones and flattened boobs, there’s no way Julie Andrews or Renate Müller could’ve been mistaken for a man. But so well-done are both versions of this comedy, we buy into the subterfuge eagerly and happily.

This is a sparkling restoration of a greatly enjoyable movie and a smile from beginning to end of its one hour and twenty-four minutes.

***********************

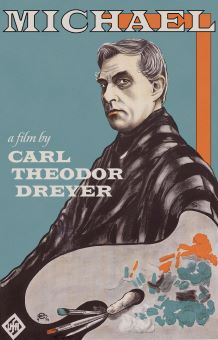

Michael

German intertitles with English subtitles | Germany | 1924

directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer

This remarkable film, decades ahead of either its time, or of acceptance of its subject matter, has been restored to crisp perfection.

Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer in 1924, Michael deals with a homosexual relationship between an ageing artist and his bisexual model. At its release, it drew many negative reviews, though now it’s seen as a prime example of Dreyer’s expertise in visual story telling, as is his famed The Passion of Joan of Arc.

Alternatively titled Mikaël, Chained: A Story of the Third Sex, it deals with a famous artist, Claude Zoret, who falls in love with his handsome model, Michael, and invites him into his palatial home. The two live together in harmony until an impoverished countess comes to Zoret to have her portrait painted. She sees Michael as a means of robbing Zoret of his fortune. She seduces Michael and uses him to steal from Zoret. Only when Michael sells the prized portrait of himself which brought him and Zoret together, does Zoret realize what’s been going on. It crushes him artistically and his health declines. Dying, he sends a message to Michael to come to his bedside, but the countess intercepts the message and Michael receives it too late. Zoret’s last words reflect his emotional commitment regardless of Michael’s betrayal: “I can die in peace, for I have seen true love.”

The screenplay by Thea von Harbou (Metropolis) adheres closely to the source material, Herman Bang’s 1902 novel Mikaël. It’s believed Dreyer chose the subject because it echoed his own unhappy homosexual relationship. The photography by two giants of the industry, Karl Freundt and Rudolph Maté, is superior to much of the cinematography of the period. In spite of the static camera, scenes are beautifully composed and lit. Michael’s descent into duplicity is perfectly stated visually as, in one scene, he stands in the foreground entirely in shadow, while the palatial room beyond him is in full light. And while there are no pans or traveling shots, the camera giving us no point of view, the editing is far ahead of its time, interspersing extreme close-ups to heighten the emotional relationship between characters.

Benjamin Christensen as Zoret is a somber, dignified figure and the Michael of Walter Slezak, attractive in his pre-Hollywood character days, is at turns gauche and sly.

The film was groundbreaking in its day and influenced many contemporary directors, one of them Hitchcock who derived elements of Michael for his 1925 Blackguard.

***********************

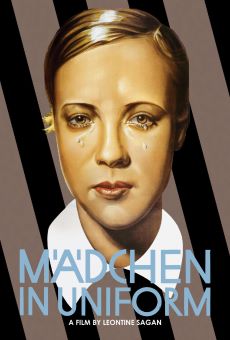

Mädchen in Uniform

German intertitles with English subtitles | Germany | 1931

directed by Leontine Sagan

Perhaps the best known of these three worthy restorations is the German Mädchen in Uniform, derived from Christa Winslow’s play, Gestern und Heute (Yesterday and Today). This moving story of lesbian love was groundbreaking in its day, eclipsed only by the ongoing cult status of the more sensational Blue Angel, released a year before.

Initially, it was a great success in some European countries, specifically Romania, and at the Venice Film Festival where it won the highest audience approval for technical achievement, and also in Tokyo where it won Best Foreign Film in 1934. However the film was, not surprisingly, banned outright in the U.S. until the ’70s, and even then shown in heavily edited versions. This restoration repairs some of those censorship injustices.

Here is one of the most memorable and moving of the pre-Hitler German talkies. 14-year-old Manuela (Hertha Thiele), virtually abandoned by her family, is a new student in an upscale girls’ boarding school. A loner, she remains apart from the other students and is persecuted by the prim, authoritarian headmistress determined to keep rule with an iron fist. One teacher (Dorothea Wieck) is sympathetic to Manuela’s loneliness and the friendship turns into a romance. Upon revelation of the relationship, Manuela attempts suicide and is saved by the students and the sympathetic teacher. The defeat of the principal’s totalitarian dictatorship gives the film it’s final, moving scene as she walks the length of the school corridor alone, in shame and in silence.

The universally splendid female cast is directed with appropriate subtlety by Leontine Sagan. Her camera never imposes, but maintains relative objectivity, allowing the audience to draw conclusions. The whole is accompanied by an accessibly lyrical score by Hanson Milde-Meissner.

An important landmark in the history of queer cinema, Mädchen never flinches from its honesty in depicting first love. It’s also recognized as a thinly veiled indictment of innocence versus oppression. This is particularly poignant and relevant as it was produced during the Nazi rise to power. Sagan, a Jew and a lesbian, wisely fled Germany right after the release of this film and went on to a substantial career in the U.K. as a theatre director.

These three important films are restored to pristine perfection by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Foundation, the Deutsches Filminstitut, the Danish Film Institute, and the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv. All have newly translated English subtitles and are released by Kino-Lorber and available in virtual screenings as well as on DVD.

***********************

With theaters closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this film will be released in “virtual cinemas” supporting independent art houses. Click here to find a theater near you to support. For more new releases at local cinemas, visit Kino Marquee.