NEAL IN GRATITUDE

As biographies of Hollywood’s Golden Age continue to roll off the assembly line, their subjects seem to fall into two categories: victims and survivors. Of the two we like the victims best – eternally beautiful, forever young, a twentieth century communion of saints presided over by the trinity of Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe and James Dean. The survivors can be more problematic, showing up on award shows in out-of-date evening wear, straining to read the teleprompter without glasses, reminding us that we don’t look as good as we used to either.

But real lives are not so easily pigeon-holed, and there is a third, more disparate group — the victims who survived. Patricia Neal, portrayed here with loving detail by Stephen Miller Shearer, fell victim to a series appalling misfortunes but ended triumphantly in the survivors’ camp. Though her fame never reached the dizzying heights of some of her contemporaries, Neal’s talent was indisputable, and her life more dramatic than any other woman of her generation.

Patsy Neal at age twelve, 1938.

Born in Packard, Kentucky, Patsy Louise Neal was raised in Knoxville, Tennessee. Like many a future star she came to performing early, taking acting and dance classes and appearing in school and local plays. She studied drama at Northwestern University but never graduated, and hit New York in 1945 at the age of nineteen. Postwar New York theatre was at an all-time high. Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller’s first plays were being produced, Elia Kazan and Cheryl Crawford had just founded the Actors Studio, and an exciting new generation of actors, writers and directors were making themselves heard.

Patsy Neal at age fifteen, 1941.

After a slow start, Neal’s big break came in 1947 in Another Part of the Forest, Lilian Hellman’s prequel to The Little Foxes. In playing the young Regina, Neal risked comparison with Tallulah Bankhead and Bette Davis, who had both played Regina in The Little Foxes. With rave reviews and a Tony Award to her credit, Neal’s future as a stage star seemed assured – she was even tipped her as “the next Katharine Cornell”. But the day of Cornell, Lynn Fontanne and Gertrude Lawrence, the great ladies of Broadway who achieved stardom without benefit of celluloid, was over. Air travel had made it easy to commute between Broadway and Hollywood, or between Art and Commerce as many viewed it. Patricia Neal became one of a new generation of bicoastal artists, as at home on a film lot as on a Broadway stage.

After the elation of Broadway stardom, Warner Brothers was a dash of cold water. Like most contract players in the studio era, Neal was often forced into unsuitable roles in undistinguished films. Her first outing, John Loves Mary, was about as exciting as you’d expect a film called John Loves Mary starring Ronald Reagan to be.

Of more interest than Neal’s film career at this time, particularly to the gossip columnists, was her affair with Gary Cooper, Middle America’s Golden Boy, though by 1949 the gold was more than a little tarnished. Cast as his love interest in The Fountainhead, Neal soon became his off-screen love interest. Cooper’s Roman Catholic wife refused to give him a divorce, and when Neal found herself pregnant a choice had to be made. Hollywood was still puritanical back then, and moviegoers were led to believe that the stars’ private lives were as blameless as their own. Fresh in the memories of transgressors was the fate of the adulteress Ingrid Bergman, banished to Europe and condemned to making art house movies for ten years. Aware of this, Neal surrendered to Hollywood hypocrisy and had an abortion, a decision she regretted for the rest of her life.

Of the dozen films Neal made at this time, only one is memorable. The Day the Earth Stood Still is one of the best science-fiction films of its time, until Kubrick’s 2001 knocked them all out of the park in 1968. The poor performance of Neal’s films combined with fallout from the Cooper affair resulted in her 20th Century Fox contract not being renewed. The antipathy was mutual and by the end of the year she was back on Broadway in Lilian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour.

Patsy Neal at age eighteen, Northwestern University, 1944.

It was Hellman who introduced Neal to the next, and ultimately the most important, man in her life. Born in Wales to Norwegian parents, a Royal Air Force fighter pilot and a friend of Bond’s Ian Fleming, Roald Dahl cut a dashing figure, and Neal had found the father for the children she craved. Their marriage endured for thirty tumultuous years and produced five children, but it was never less than troubled. Shearer’s account of it makes for some very grim reading.

For the first ten years, before Dahl’s writing career took off, Neal was the one making all the money, a blow to Dahl’s considerable ego. In addition, his conception of a woman’s place in a marriage was retrogressive even by 1950s standards. A 1967 interview quotes him as saying, “When I first married Pat, I thought it would be difficult to train her, but it hasn’t been.” This about the woman who supported him for years. Similarly, “Old Pat was out there, able to make enough money to keep me going.”

Patricia Neal and Roald Dahl, circa 1962.

Through it all Neal continued to juggle family and career, traveling wherever work took her. The most interesting film of this period is A Face in the Crowd, which prophetically anticipated the impact of television on the public consciousness. Neal plays the manager of a supposedly salt-of-the-earth TV celebrity who is in fact a cynical megalomaniac. Neal’s character exposes the sham by opening a mike, broadcasting his contempt for his fans over the airwaves. Shearer suggests that A Face in the Crowd has lost its relevance and that today’s television audiences are less gullible than they were in the 1950s. That may have seemed the case in 2006, but political events of the last five years have made the film more chillingly relevant than ever.

Shearer is at his strongest in portraying the Dahls’ tempestuous marriage and the tragic events that finally destroyed it. In 1960 their four-month-old son Theo’s baby carriage was hit by a taxi on a New York street. The resultant brain damage led to years of therapy and multiple surgeries. Two years later, while the family was still grappling with the trauma of Theo’s accident, six-year-old Olivia contracted measles and died within a few days. These two tragedies cast a deep shadow over the Dahls’ marriage. A third would eventually destroy it.

Patricia Neal in 7 WOMEN, February 1965.

By the early sixties Dahl was a highly successful author and the pressure on Neal to accept any and all work lessened. Back in Hollywood in 1965 to film 7 Women, she was pregnant with her fifth child. On her first day of filming she suffered a massive stroke and almost died. After months in intensive care she gave birth to her fifth child. It would be another three years of aggressive therapy before she was able to work again. The account of Neal’s recovery and the support she received from Dahl and a group of friends is one of the most moving in the book.

By the time she was able to accept work again, Neal was in her early forties, not a good age for an actress in any era. She returned to the screen, getting a second Oscar nomination for The Subject Was Roses, but from that time on her career was mainly in character roles on television, including a spate of “disease of the week” movies in the 70s and 80s. Of more importance was her active involvement in charities and organizations devoted to helping stroke victims.

Patricia Neal, circa 1990s. Photo by Bill Donovan.

This book is a revision of the original published in 2006, four years before Neal’s death, written with her approval and collaboration, which suggests it is an authentic account. Mr. Shearer has done a terrific job of organizing an enormous amount of material into a cohesive narrative. If I have a criticism it is that he falls into a common biographer’s trap of sometimes giving us too much information. Great actress that she undoubtedly was, the undeniable fact is that Neal made only a handful of important movies. After The Day the Earth Stood Still, A Face in the Crowd, Hud and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the quality falls off dramatically, and at times the book dwindles into a laundry list of forgotten movies and long-since-erased TV episodes, which makes for very dry reading.

Patricia Neal’s extraordinary strength in the most terrible adversity is her true story, and that is where the strength of Shearer’s book lies.

photos courtesy of University Press of Kentucky

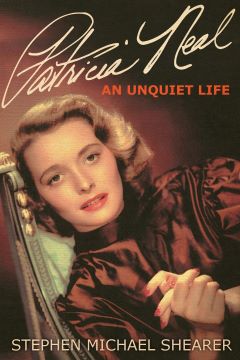

Patricia Neal: An Unquiet Life

Stephen Miller Shearer

University Press of Kentucky; updated and expanded edition (March 16, 2021)

English | 520 pages | paperback

available at Amazon