LEIGHWARD

“A consummate actress, hampered by beauty” is how George Cukor, the original Gone with the Wind director, described Vivien Leigh.

Leigh is almost unique among movie stars (a label she detested) in that she was as celebrated on the stages of London and New York as on the cinema screens of the world. Best known today for her Oscar-winning roles in Gone with the Wind and A Streetcar Named Desire, she made only nineteen films in thirty years, at the same time appearing on stage in everything from Shakespeare to Chekhov to musical comedy. As wife and acting partner of Laurence Olivier, the greatest classical actor of his generation, she was theatre royalty in an era when royalty was revered rather than tabloidized. For twenty years the Oliviers were the most famous acting couple in the world. When their marriage fell apart in the late fifties, Leigh continued to star above the title for the rest of her too-short life, even making a Tony-winning foray into musical theatre.

Such is the enduring nature of Leigh’s beauty, talent and sheer star quality that, fifty-six years after the release of her last film, her name is still synonymous with a vanished breed of glamour. There are to date seven full-scale biographies devoted to her, the most recent published only two years ago, and today her name is back in the headlines because of controversy over Gone with the Wind.

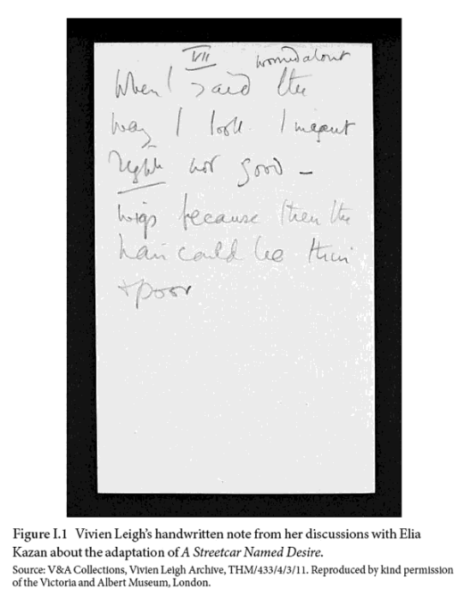

REFRAMING VIVIEN LEIGH: Stardom, Gender and the Archive by Lisa Stead, is a significant addition to the existing studies of this unparalleled artist. It is in no sense a conventional star biography; Stead takes a much more radical, and highly original approach. As Leigh’s contemporaries are no longer with us to tell the tale, Stead has mined the various archives devoted to her, especially the Vivien Leigh Archive in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Archival research may sound like a dry-as-dust way to address such a glamorous subject, but as Stead points out, a scribbled pencil note to a director can tell us more about its writer than the questionable reminiscences of former colleagues. Leigh’s chronological facts having already been exhaustively documented, Stead explores key aspects of her life in greater detail than her previous biographers.

To investigate Leigh’s working method in detail, Stead has selected archival material from her work on two films, A Streetcar named Desire (1951) and the lesser-known Ship of Fools (1965). A Streetcar Named Desire is of particular interest because Leigh also played the role of Blanche on the London stage, directed by Olivier. Her status as a bona fide Screen Goddess made her something of an interloper in the parochial world of West End theatre, and Streetcar is the project where Leigh’s two worlds collided to spectacular effect; cast in the film, Leigh became one of very few actors to play a role on film which they had created on stage.

The archive approach pays off handsomely here. Making extensive use of memos, script notes and correspondence with Elia Kazan, who also directed the play on Broadway, Stead charts Leigh’s journey in adapting her iconic stage performance to the different demands of the screen. The correspondence with Kazan also shows a commitment to the production as a whole, over and above attention to her own performance. Leigh offers perceptive suggestions for script cuts and ways to get the more controversial aspects of the story past the still-powerful Production Code.

If Streetcar shows Leigh at the height of her powers as an actress, the other film detailed here, Ship of Fools, finds her at a very different place in her career. Fifteen years after the triumph of Streetcar, she is actively transforming herself from glamorous star to character actress.

If Streetcar shows Leigh at the height of her powers as an actress, the other film detailed here, Ship of Fools, finds her at a very different place in her career. Fifteen years after the triumph of Streetcar, she is actively transforming herself from glamorous star to character actress.

Handwritten notes in Leigh’s own Ship of Fools script reveal her exacting work method, with attention paid to every detail from line-readings and facial expressions to the importance of costume, hair and makeup in creating a character. They also highlight her involvement in other aspects of production, including insightful suggestions on script cuts and rewrites. On watching these two films again, Leigh’s seemingly effortless performances are clearly the result of meticulous preparation.

The other subject covered in detail here is Leigh’s fragile mental health which dominated her private and professional life. Stead digs deep into archive material relating to Leigh’s mental breakdown of 1953 which led to her being unable to complete work on the film Elephant Walk. She was replaced by the equally troubled, but ultimately more resilient Elizabeth Taylor. Letters from fans at this time testify to the place Leigh held in the public’s affection. In the fifties mental illness was still regarded with shame rather than compassion, and many of the letters share the writers’ own experiences of mental problems in ways they might be unable to do with their own friends and family. Such correspondence presents a chilling picture of the lack of understanding of mental health issues at that time.

While much of her book is accessible to the general reader, Stead’s highly detailed account appears to be aimed mainly at the serious student of theatre and film. The Introduction in particular reads suspiciously like the opening chapter of a doctoral dissertation, which maybe it originally was. The reader is bombarded with daunting words like “historiographic”, “interdisciplinary” and “decontextualized”. Scholarly writers all too often use a ten-dollar word where a fifty-cent word would do, but the proliferation (Stead’s got me doing it now!) of such terrifying words, along with the curious use of the word “labor” for “work”, leads one to suspect that Oxford University Press is paying its writers by the syllable.

Fortunately, after the Introduction, Stead mostly drops the dissertationese and reverts to plain English. This is very much to the good as Stead’s plain English is as intelligible to the casual reader as to the academic. Most importantly, Vivien Leigh is presented here as a much more complex, intelligent woman than the generally accepted image of Screen Goddess, Tormented Beauty, and Great Lady of the Stage. Ms. Stead has created an unforgettable portrait of a professionally triumphant, privately tragic life.

Reframing Vivien Leigh: Stardom, Gender, and the Archive

Oxford University Press

264 Pages | 10 illustrations | paperback | published March 1, 2021

6 1/8 x 9 1/4 inches | ISBN: 9780190906511

also available as Hardcover and eBook at Amazon