WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? NOT MUCH

I’ll begin as author David Curtis does, with a quotation from Elizabeth Bowen:

“I go to the cinema for any number of different reasons’¦ At random, here are a few of them: I go to be distracted (or ’˜taken out of myself’); I go when I don’t think; I go when I do want to think and need stimulus; I go to see pretty people; I go when I want to see life ginned-up, charged with an unlikely energy; I go to laugh; I go to be harrowed; I go when a day has been such a mess of detail that I am glad to see even the most arbitrary, the most preposterous patterns emerge; I go because I like bright light, abrupt shadow, speed; I go to see America, France, Russia; I go because I like wisecracks and slick behaviour; I go because the screen is an oblong opening into the world of fantasy for me; I go because I like story, with its suspense; I go because I like sitting in a packed crowd in the dark, among hundreds riveted on the same thing; I go to have my most general feeling played.”

This, by one of the most cerebral of twentieth-century novelists, is pretty much a love letter to the power of commercial cinema. It’s a curious choice to open a book on the virtues of decidedly uncommercial cinema: almost none of the elements Miss Bowen considers essential to a successful film are present in the work discussed in Curtis’s book. Of course Bowen was writing in 1937, when to most people, art was something you hung over the sofa, but the visceral appeal of cinema has not changed.

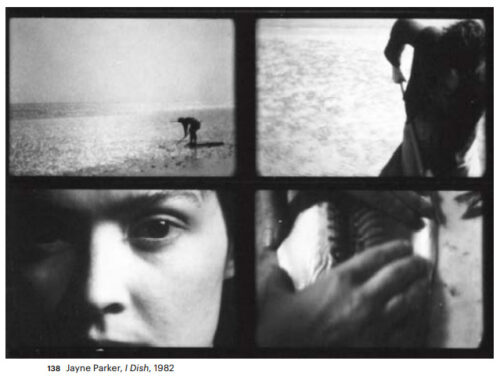

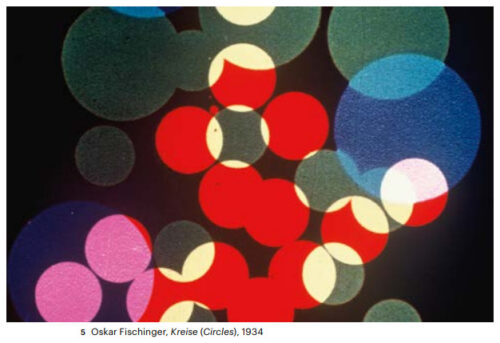

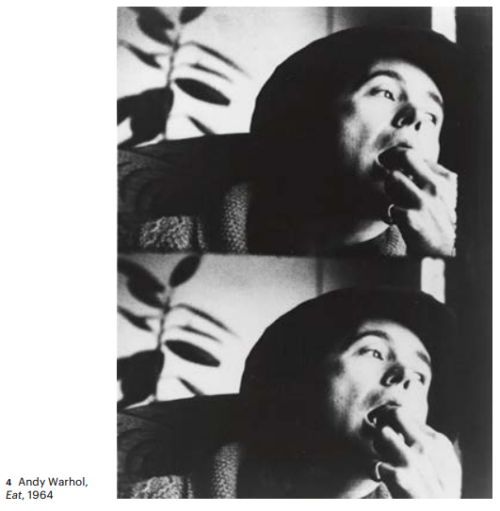

In Artists’ Film, Curtis explores a very different kind of cinematic experience. His definition of an artist’s film is broad enough to embrace classic features such as Robert Wiene’s silent melodrama The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou, abstract animated shorts, and Andy Warhol’s interminable human still-lifes. Unfortunately his use of the word artist carries with it the involuntary implication that the makers of such films as (randomly) Intolerance, La Dolce Vita, or Reservoir Dogs are not really artists. It’s telling that the makers of these and other highly influential works get nary a mention in Curtis’s text. He also fails to explore any influence the commercial cinema might have had on artists’ cinema, or vice versa, and truth to tell, there’s very little; for the most part, the medium of artists’ films exists in its own tightly sealed box.

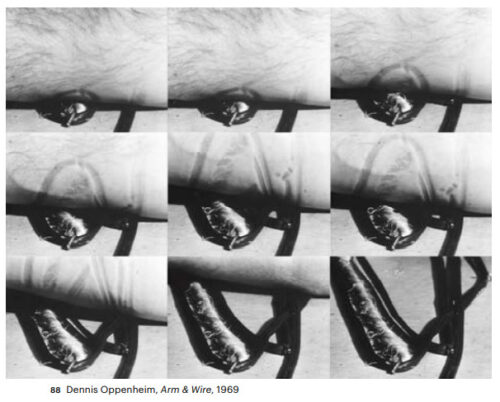

The main attraction of these films for Curtis appears to be that they’re made by artists rather than mere directors, and frequently by artists whose premier mode of expression is not film; to put it another way, they are artists first and filmmakers second. By their own admission many of them have only a passing acquaintance with the technical aspects of cinema, and not much interest in learning them. Craftsmanship is seen as somehow suspect, an unwelcome diluting of raw talent. Consequently many of the films discussed are the work of enthusiastic amateurs testing the waters of an unfamiliar medium.

But it has to be admitted that there’s a certain charm in the delight these artists take in discovering a shiny new toy to play with. Witness the work of Marie Menken, a key figure in the New York avant-garde film scene; some of her (mercifully) short subjects would get her kicked out of any self-respecting director course. And Andy Warhol’s ventures into film, though frequently fascinating, have little of the power and visual impact of his paintings.

Many of these filmmakers (okay, artists) seem to make it a point of honor to reject such degenerate aspects of mainstream cinema as well-framed shots, a coherent storyline, and logical editing. And speaking of editing, Curtis tells us, apparently without irony, that one of the editor’s chief functions is to keep the viewer awake.

Unfortunately, by ignoring such a basic element as narrative, they are often throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Narrative (or as Elizabeth Bowen has it, “story, with its suspense”) is the hook that reels us in; keeping us in suspense makes us more receptive to what the filmmaker wants to tell us. Many of these artists have a story to tell, but in their rejection of narrative they are depriving themselves of one of their most useful tools. If we don’t care what happens next, how are we to involve (let alone immerse) ourselves in their work?

In the sixties and seventies of the last century, many highly respected directors, mainly in Europe, began to shy away from story. Their work was greeted with adulation by most critics and by a limited section of the film-going audience. This cult of non-narrative film even invaded mainstream cinema when directors such as Michelangelo Antonioni and Alain Resnais achieved financial as well as critical success. Most of these films are now pretty much consigned to film school courses and the occasional art house screening, whereas many commercial films of the period survive to tell us far more about the zeitgeist of their time than those inward-looking epics. Film societies dutifully screened Zabriskie Point and Chelsea Girls, and members dutifully watched them before hurrying off to catch Bullitt or Bonnie and Clyde at the multiplex. God knows Hollywood needed a shot in the arm by that time, but it was Easy Rider, The Graduate and Midnight Cowboy that really shook the old place up.

But by 1968, even Andy Warhol had embraced narrative, just as a generation earlier in France Jean Cocteau abandoned the surrealism of Le Sang d’un Poete and embraced mythology — that most elemental form of story-telling — in La Belle et la Bête and Orphée, thereby securing himself a place in the pantheon of great filmmakers.

Of course, the most welcoming platform for the book’s subjects is and always has been the avant-garde, which was particularly alive and well in New York in the fifties and sixties. If Florence was home to the Renaissance, New York was home to the avant-garde, and Andy Warhol was its Michelangelo. But in spite of enormous publicity, particularly for Warhol and his famous Factory, the influence of these films has mainly been on other avant-garde filmmakers. The avant-garde has a distressing tendency to feed on itself, a never-ending cycle reminiscent of a serpent devouring its own tail, or to put it less poetically, a dead-end street. Or even less poetically, a cul de sac.

Artists’ films are by definition a minority form of expression. Undoubtedly there’s a place (and apparently an audience) for them, but the true home of the artist’s film is not the movie theatre but the gallery, the art museum, and more recently the internet. The availability of more accessible filming techniques and viewing platforms has blurred the distinctions between painting and film, leaving the field open for multimedia work combining disparate artistic disciplines; but “discipline” is the key word here – it’s no longer enough to randomly aim your iPhone at someone or something and call it art.

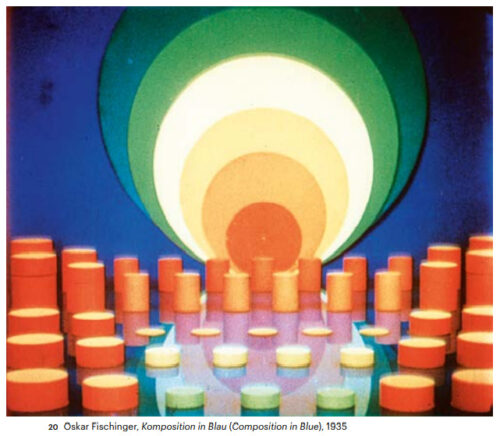

Artists’ Film is beautifully produced and gorgeously illustrated, as befits a study of this overwhelming visual medium. Mr. Curtis is an acknowledged authority on his subject and is clearly passionate about it. He states his case clearly and persuasively, but much of the self-regarding work he celebrates seems inevitably, and in some cases deservedly, destined for oblivion.

On the whole, watching someone indulging in masturbation is a lot less fun than performing the act oneself.

Artists’ Film

Thames and Hudson

October 5, 2021

340 pp | 153 illustrations

$27.95 original trade paperback | ISBN: 9780500204733