CHEAP THRILLS WON’T LIFT YOUR SPIRIT

You never forget your first. Mine happened in the West End of London in the year 2000. The Woman in Black (Stephen Mallatratt’s adaptation of Susan Hill’s gothic horror novel) marked the first time I was ever scared shitless in a theater. Not a movie theater, mind you: the stage. That magical place where actors — real as can be — stretch your imagination like taffy. Under the spell of their illusion, I experienced dread and the creeps. It’s the first time where I, in a live theater, had chills coursing through every inch of my body. My god, I was terrified; unabashedly in love. It’s a feeling I’ve been chasing ever since.

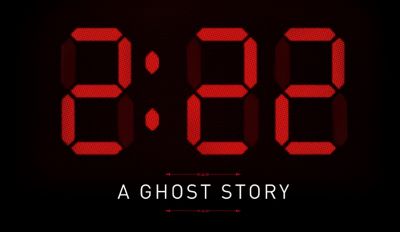

Cut to 2022: Los Angeles. It’s here, at the Ahmanson Theatre, that I had hoped Danny Robins‘ Americanized version of his British hit play 2:22: A Ghost Story could deliver for me a similar experience. While its British counterpart was awarded Best New Play, the work sadly doesn’t hold a candle to the Woman Robins admits inspired it. Sure, 2:22, like that legendary classic, startled me — a few times. It even provided those elusive shivers I’ve long been seeking in a stage show. But unlike its predecessor, 2:22 doesn’t add up and so little of its thrills are rightly earned.

Anna Camp and Constance Wu

It all starts with an onstage clock. Over two acts, it looms — sometimes stalling, sometimes careening toward that titular hour. Designer Lucy Carter has lined the stage with red neon lights that mirror its digital fluorescence. Inside this unnerving framing lives a bickering married couple, Jenny (Constance Wu) and Sam (Finn Wittrock). Their cavernous Boston home is stylish amidst renovations, yet filled with little warmth. (Design by Anna Fleischle.)

Inside, Lauren (Anna Camp) and her new beau, Ben (Adam Rothenberg), are mingling with their hosts: there are drinks aplenty, and a dinner they’ll barely eat. For the past four nights, Jenny’s been experiencing hauntings from a ghostlike entity, always at 2:22 a.m. More disturbing, the specter is often heard through a baby monitor around the hosts’ sleeping infant. Sam, however, has missed all of this as he’s just returned home from a recent trip. Jenny, clearly troubled, wants to prove to him and their guests that she isn’t crazy. She invites them all to stay up with her to witness the next visitation. As you can imagine, it’s gonna be a bumpy night. But not just for them — for all of us.

Constance Wu, Adam Rothenberg, Anna Camp and Finn Wittrock

Let’s start with the shouting. The actors are miked but you’d think they were delivering lines to people across the street. Just as disappointing are the play’s largely one-note and contrived characters. Mr. Rothenberg as Ben is the only one whose performance doesn’t come across as over-the-top and unmotivated. With such melodrama, it’s hard to care for these people, much less buy their relationships. The hosts’ marriage is especially suspect. Between their constant jabs and lack of chemistry, it makes one wonder what brought them together in the first place. The unnatural, heightened dialogue doesn’t help any of this.

The clash between faith and reason is one of the play’s major themes, and yet it’s handled so cartoonishly. Sam, for instance, is a science-minded astronomer. Because he insists upon rationality to explain curious phenomena, he’s made out to be an even bigger villain than the alleged ghost haunting his home. He’s smug and (possibly) insecure, a perfect punching bag for the believers in ghosts and god. His wife, for instance, in light of recent events, seems to be returning to her Catholic roots; meanwhile Ben, a good faith simpleton, loves talking about his ghost-hunting ‘vigils.’ While colliding worldviews can be intellectually stimulating, here they’re hardly given a fair fight.

Anna Camp, Constance Wu and Adam Rothenberg

The play’s scares are yet another missed opportunity. It’s not enough to fear an alleged ghost. In order for an audience to be scared for any particular character, we first have to be invested in them. The most compelling thing 2:22 has to offer in this regard is the threat to an innocent (offstage) baby. The plot, too, is lackluster. From the start, it’s clear that 2:22 is destined for a specific target: 2:22 a.m. Until then, we wait. And wait. All while watching the clock. It’s not until the last half of the second act that things actually get exciting. Before then, the play kills time with unrelated subplots, like having characters share scary stories from their past rather than dealing with the actual ghost story at hand. This isn’t a ‘slow build,’ it’s a ‘no build.’

That said, the play scores a few jump scares. Sound designer Ian Dickinson is credited for our hearing loss having ear-piercing screams blasted throughout the theater. These are cheap tricks, though. The screams are unconnected to the diegesis (world) of the story. Sure, they’re startling, but they mostly highlight how little the script can elicit thrills on its own — until the end, that is. That’s when the work finally grounds us in its original premise. It’s also when designer Chris Fisher (by way of Will Houstoun) is most able to work his theatrical magic. This collision of storytelling and illusion allows our fears to occur organically. Such feats, along with the play’s welcome (if era-specific) humor, prove that Robins and director Matthew Dunster — at least occasionally — know what they’re doing. If only they could sustain it.

Anna Camp, Finn Wittrock, Adam Rothenberg and Constance Wu

photos by Craig Schwartz Photography

Constance Wu and Finn Wittrock

2:22: A Ghost Story

presented by Center Theatre Group

The National Theatre and Neal Street Productions

Music Center’s Ahmanson Theatre, 135 N. Grand Ave.

ends on April 6, 2022

for tickets, call 213.972.4400 or visit CTG

*After 33 years, The Woman in Black will end its West End (London) run on March 4, 2023

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Guess what? I want to see it anyway.