WHITE GIRL IN DANGER IS IN DANGER

Broadway wunderkind Michael R. Jackson is back on the boards at Second Stage’s Vineyard Theatre, writing the book, music and lyrics for his latest effort titled White Girl in Danger. This new musical treads similar thematic ground as his smash hit A Strange Loop — which won the 2022 Tony for Best Musical and Jackson himself winning a Tony for Best Book of a Musical. As with A Strange Loop, White Girl features a young African-American character who is acutely aware of the pitfalls of aspiring for acceptance by an exclusionary, dominant cultural (i.e. White) value system — yet is determined to be included anyway.

Lauren Marcus and Liz Lark Brown

Lauren Marcus and Liz Lark BrownThe switch is while the central character in Loop is male; the White Girl protagonist is female — and fictional — within the world of the play. While Loop looked at the difficulty of creating within a racially oppressive value system, White Girl examines the difficulty of being the product created within that racially oppressive value system.

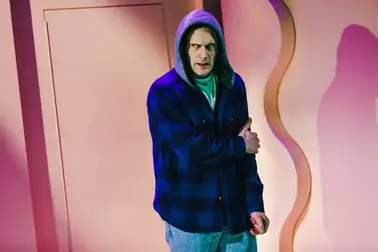

Eric William Morris

Eric William MorrisSet in a throwback world of ’˜80s soap opera (and ’80s influenced music), Jackson’s melodramatic metaphor is rarely nuanced or insightful and mostly paints with the broadest of strokes. There is a genuine and compelling surprise twist towards the end of the show and one questions why the journey to that very valid observation is so muddled. Unfortunately, the answer may be held within another reveal provided in the play. Protestations to the contrary, the show is less interested in that surprise twist than in Jackson’s own creative difficulties.

Latoya Edwards

Latoya EdwardsIt seems there’s a television soap opera called “White Girl in Danger” that somehow manages to utilize every stereotypical trope about victimized, young, white women that was ever created by the Hollywood story machine. The show’s three main characters are white high school girls — Megan White, Maegan Whitehall and Meagan Whitehead. They live in a town called Allwhite that is populated by only White People with the exception of a few minor, Black characters who live in the Blackground. The three girls battle low self-esteem, high self-esteem, codependence, independence, eating disorders, abusive boyfriends, too much money, too little money, drugs, sex, overbearing mothers, uncaring mothers and a killer who begins murdering all the young white girls in town with impunity.

Molly Hager, Lauren Marcus

Molly Hager, Lauren MarcusInnocuous Black teenager Keesha, tired of living in the Blackground, decides she wants the all powerful white writer of the series to center her in her own story, or rather, center her in one of the white girl stories. For Keesha, the white girl stories are better because the powerful head writer can only write Black stories that concern sassy black women, slavery, young black men in trouble and rough times in the ghetto. Keesha’s mom Nell, the high school cafeteria lady, tries to warn her daughter against leaving the Blackground but Keesha doesn’t listen (why should she when white girls don’t listen to their mothers). Eventually, Keesha is happily centered in her own white girl story. But her joy is short-lived because this is a soap opera and Keesha’s dream soon becomes ’¦ a nightmare!

The Company of WHITE GIRL IN DANGER

The Company of WHITE GIRL IN DANGERJackson broaches a wide span of ideas in this piece but does he have to say all of it at the same time? There’s multiple storylines and multiple commentary about the meaning of these stories plus a new song practically every five minutes. And there’s a Battle of the Bands – presumably because it’s an ’˜80s suburban high school so why not? Also, Jackson not only deals with stereotypical white girl media presentation (yet with no take on the validity of those reductive story norms) he also characterizes Black women by resurrecting ’˜80s sitcom portrayals. There must be a reason for reviving Nell Carter’s “Nell” from Gimme a Break or Marla Gibbs’s “Florence” from The Jeffersons or Jackee Harry’s “Sandra” from 227. Most likely they are included to demonstrate the limited nature of these creations but that is not exactly clear.

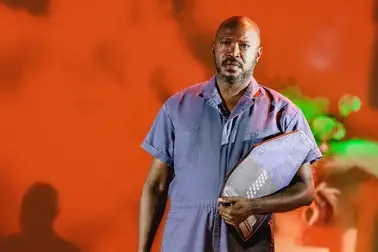

James Jackson Jr.

James Jackson Jr.Jackson’s considerable talent for wordplay is on full force in this three-hour outing but even that cleverness starts to wear thin. And though set in the Eighties, current conversations around justice, inclusion and representation, even beliefs deeply held by the African-American Civil Rights Generation don’t escape his borderline cynical critique. Direction by Lileana Blaine-Cruz and choreography by Raja Feather Kelly are very good considering their main task may have been to find a way to squeeze all of these ideas onto one stage. Yet even with that yeoman effort, the show plays tonally ambivalent — never quite sure if it’s a comedy, satire, drama, etc. Even the singers and the musicians often seem at odds with each other instead of working together — with the orchestra sometimes drowning out the performers.

Lauren Marcus, Molly Hager, Alyse Alan Louis, Latoya Edwards

Lauren Marcus, Molly Hager, Alyse Alan Louis, Latoya EdwardsThe bright spot of the show are the multi–talented singer/actor/dancers that grace the stage and somehow successfully manage the voluminous amount of material they have to contend with. As the three white teen girls, Molly Hager, Alyse Alan Louis and Lauren Marcus are equal parts funny and compelling as they navigate their roller-coaster lives in Allwhite. Understudy Alexis Cofield mostly shines brightly as leading role Keesha — though there was occasional tentativeness in her approach. Eric William Morris proves himself quite good in portraying three types of generic young white guys that were staples of ’80s television. Understudy Ciara Alyse Harris is very funny as a higher-strung version of television maid Florence Johnston as is Jennifer Fouche’s sexpot Abilene. A Strange Loop favorite James Jackson Jr. joins this cast as kindly school janitor Clarence and is tasked with delivering a pages long monologue that reveals a plot twist to end all plot twists– and he does so brilliantly.

Kayla Davion, Morgan Siobhan Green, Jennifer Fouche

Kayla Davion, Morgan Siobhan Green, Jennifer FoucheBut the real center of the show is Tarra Conner Jones as Nell, a heightened version of Nell Carter’s sitcom character (another maid). Making Ms. Carter’s creation her own, Ms. Jones delivers a comical, belting, moving, tour-de-force performance as a woman who seems to embody black pain, black joy, black humor, black wisdom, black survival and black love all at once. If there is a reason to see this show, it is to witness Ms. Jones’s multi–faceted, star-making performance. Scenic Design by Adam Rigg and Costume Design by Montana Levi Blanco give the show an authentic ’80s look and big hair abounds, thanks to Hair and Wig Design by Cookie Jordan.

Tarra Conner Jones, Latoya Edwards

Tarra Conner Jones, Latoya EdwardsThere is a good, possibly important show buried within this current incarnation of White Girl In Danger. Mr. Jackson is correct in his continual excavation of the power of storytelling — particularly whose gaze dictates the story and whose lives are affected by it. And where this show eventually leads is actually quite an amazing and original destination. Here’s hoping Mr. Jackson and his creative team find a more direct route there in the future.

Latoya Edwards

photos by Marc J. Franklin

Vincent Jamal Hooper and Latoya Edwards

White Girl in Danger

Second Stage Theatre and Vineyard Theatre

Tony Kiser Theatre, 305 West 43rd St.

opened April 10, 2023; ends on May 21, 2023

for tickets, call 212.246.4422 or visit 2ST