THIN LOVE

We go to the ballet for bodies. Don’t we? If the dance audience at The Wallis in Beverly Hills, where I saw Alonzo King LINES Ballet’s Deep River yesterday (there is one more performance tonight, June 10), were presented with a version of the AMC Theater’s Nicole Kidman promotional trailer, what would she say to us? “We come to this place’¦” For music? For movement? To see and be seen in our boots and suits? Yes, all, but we really come to this place to sit for an evening and watch bodies. In all their sinuous, sweating, stretching and snapping glory. For the uninitiated, here’s everything you need to know about dance: it’s both the highest and lowest art form. Balanchine’s Serenade and the stripper pole are unlikely but unmistakable twins, entangled in an interminable tango simply because of their common placement of bodies – before a viewer, on a giant pedestal.

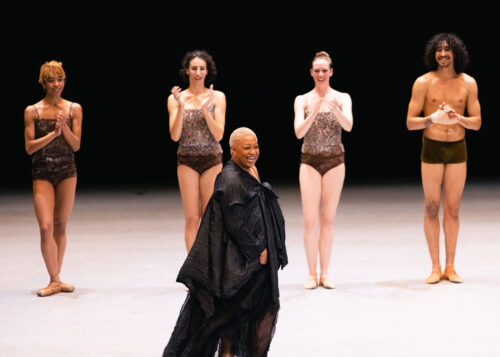

Deep River, choreographed by Alonzo King for the 40th anniversary of his eponymous company, presents no shortage of what we came for, if skin be the game. Interacting with and to a live vocal performance by Lisa Fischer, with other original music by Jason Moran (and excerpts from Pharoah Sanders, Ravel, and James Weldon Johnson), King’s thirteen sculpted dancers bare plenty as they skim, preen, and agitate the air. The structure of the 65 minutes is as loose as the flowing mesh and chiffon garments the dancers wear, but this appears intentional; the program describes Deep River in abstract terms. Put together during the pandemic, it’s an evocation of the “call’¦ to look at one another as a family of souls.” Writing in my notebook in the dark, I could demarcate something like ten or more sections: unison sections melting dizzyingly into trios, pas de deux, solos. For its rapid pacing, it doesn’t feel short.

The show begins with the dancers all onstage, plumbing the air with their extremities. Lisa Fischer sings, facing them, from the downstage right corner. Her warm vocal tones evoke something ancient but unspecific – the dancers respond with what we will come to recognize as King’s signature style: a tangle of skinny outstretched limbs, staccato motions like they’re swatting mosquitos. It’s a kind of classical tarantism: ballet technique brought to ecstasy and then brought to ecstasy again, over and over, rewound, set on fast-forward.

At one point in what I will call the First Movement, unison gives way to a trio of women. They swat around each other, then one backs up into the other’s crotch, in a menage-a-trois that is over as soon as it happens, a ghost of crudeness crossed with ur-humanity. Did I just see that? The trio gives way to a section in which the dancers are all back onstage, nodding “yes,” shaking their heads “no.” I stop my meaning-making compulsions. If dance is the poetry of the body, Alonzo King is

Jorie Graham. The experience is either beautifully maddening or movement salad, and your only real choice is to be along for the ride.

The next few sections appear as a series of images. A reverse pietà as curly-locked Jesus (Shuaib Elhassan) carries the limp body of Adji Cissoko (to Fischer movingly singing, “sometimes I feel’¦like a motherless child.”) A dancer hits an inverted tilt, leg sailing above her head, to which an audience member calls out “Yes, get that thing!” There are Afternoon of a Faun references, allusions to Mark Morris’ Pacific as two men settle onto the floor, prop themselves on their arms, recline, and watch a woman dance between them. There are references to Polyhymnia in Balanchine’s Apollo, when dancers put their palms to their mouths and then yank them away, miming the emission of sound.

At some point, I realize that the dancers are not looking at us. They interact on the stage like fish in a large tank, never breaking the fourth wall, never performing explicitly. They seem deeply internally focused, timid, even as they split their legs and do four pirouettes into a sweeping motion of the arms. I surmise that this is stylistic, but I nonetheless feel disappointed. They dance as if asleep, part of a child’s bedroom ceiling light display. I come to this place for bodies, but I come here also for people. I come here to feel part of something a performer does. Whether it is by King’s spoken direction or by some consensus of the dancers, the only person onstage who ever looks into our eyes, acknowledges that we are here, with them, that we are bodies in space too – is the vocalist Lisa Fischer.

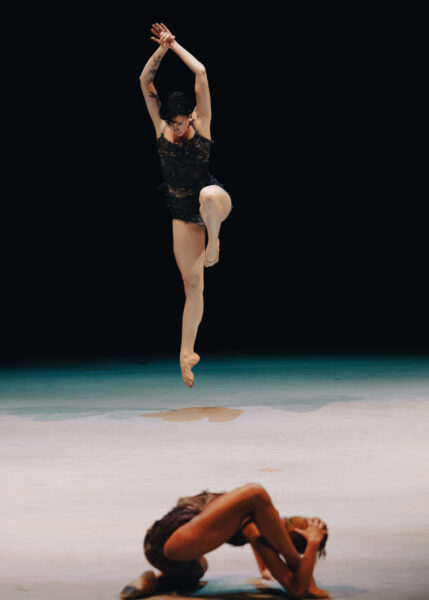

Midway through the performance, James Gowan steps onstage solo. He’s slight, but razor-sharp, fluid and avian. Between executing flapping movements that recall seagulls, dazzling pirouettes that reflect a perfect innate understanding of momentum and energy (did I count three or four?) and arm movements and one legged balances like a graceful stork, he makes eye contact with us in the audience. It’s only a split second. He ducks and emerges again with his hand pulling the skin of his face into one-half of a Grecian tragic mask. The moment is too soon over. He’s back in the fishbowl.

After Gowan’s solo, the female dancers prance onstage in pointe shoes, and it feels like King’s brought out the big guns. It’s his imprimatur. Adji Cissoko is every bit the LINES cover girl we expect in her pas de deux with Lorris Eichinger. She is a skyscraper in off-balance penchés, développés, turned-in positions that don’t have French names but strike me as a parallel universe of classical awe. As a ballet student, I would have called some of these positions (with the most extended, splayed legs or arms) “janky.” King creates a human taffy out of the “janky,” and then seems to enjoy pulling it as far as it can go before it breaks.

Toward the end of the piece, what anyone in the audience will doubtless take away from the night, Babatunji takes the stage for a solo to and with Lisa Fischer. His solo embodies light and dark in pleading motions, arm balances. At one point he appears to be suspended in the air by only his fingertips against the floor. It’s hard, I realize, to describe the movements he actually does, even though I am a trained dancer, because good dance is never only about itself. Babatunji did not do a handstand and shuffle across the floor; his arm was more than an arm. It was a flag. He was a genie, then a rope. When Babatunji finally did end the solo, head bowed, contorted, his arm dripping sullenly through the air, the audience leapt to its feet with thunderous applause. We come to this place for afterimages.

Everything after Babatunji’s solo – another pas de deux, and a final unison piece – felt anti-climactic (with the exception of Theo Duff-Grant’s flawless attitude turns). When we have seen the way light is accentuated by dark, the way lightness is made rare by weight, the last dose of King’s filigree is exhausting and unnecessary to us.

The problem with Alonzo King’s genius is that none of us watching can catch up. The technique (janky ecstasy) is so solidified, and the steps so crammed together, that they become one-note, bereft of dynamics. If everything is ecstasy, if everything is orgasm, then nothing is ecstasy, nothing is orgasm. The dancers move on top of the music; they dance on top of the steps. It’s all icing and no cake. The rare moments of unison don’t work for us as an audience. The unison doesn’t exert its special power (that trained and untrained eyes alike discern immediately) because the dancers are never dancing together.

After the performance, my companion and I discuss the choreography over Persian food in Westwood. As an Indian classical dancer, his primary way into the piece is from the lens of “structure,” but he could find none. I can’t help but agree. Deep River feels essentially unstructured, and because of that, unspecific and inarticulate. Because of its fishbowl quality, the dancers seemingly involved in their own private world, the disturbing thought occurs to me that little would be lost seeing this performance on a screen.

As we sit at the restaurant, my friend, who grew up speaking Urdu, translates a plaque on the wall for me from Farsi. He explains that the two languages use the same script, a slanted condensed version of Arabic letters. Alonzo King’s choreography in Deep River is like Farsi, if ballet is Urdu: two languages, same alphabet. King’s choreography is not ballet, but is not modern dance either, is not the amorphous “contemporary.” It’s composed of ballet’s alphabet, but it’s a language with different words, pronunciations, inflections. The problem in Deep River isn’t just that King’s choreography is cacophonous, chaotic, rushed. It is also that his dancers seem to be drowning in the learning of his language, never able to truly live in it. In spite of their great talent and proficiency, each speaks with such a different accent that one gets the sense that King’s steps are a kind of dance Esperanto: no one’s mother tongue.

I’m reminded of the oft-quoted Toni Morrison moniker, “Love is or it ain’t. Thin love ain’t love at all.” For a piece that is billed as “the power of inspiration during difficulty” and “to bloom the lotus in the muck,” the piece is too thin to contain any muck. It’s all bloom, a thousand simultaneous blooms that each are less powerful than one would be in the fullest version of itself. As algebra, or a complex language built from the alphabet of ballet, or an exercise in a contained onstage world of graceful sculptures, Deep River suffices. But as an evening of dance post-pandemic, when what is described in the program is deeply what we each crave, unfortunately Deep River ain’t love at all.

photos by Elaina Francis