CORTISOL ROCKSTARS

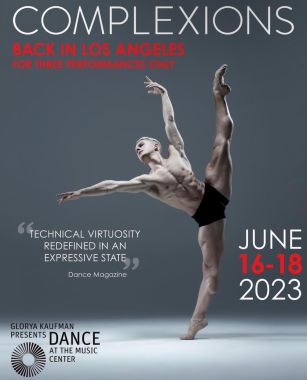

I am an irreverent narrator when it comes to reviewing dance, because I delight in the mischief of disrespecting the convention of separating creation from creator. A work most interests me as either a universe in itself (for the transcendent), or, for everything else, as an expression of a human psyche – its longings, its logic, its limitations. When a piece doesn’t transport me, I delight in parsing from it the lineages of its parent, a little terpsichorean palmistry. If you will, please indulge me that vice for a few minutes. The most interesting review I could write about the double bill of Complexions Contemporary Ballet I saw at The Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on June 16 is a brazenly psychoanalytic one.

Let’s start backwards from curtain call. The audience rises to its feet as the dancers, nineteen ripped demigods, join hands for their final bow. Two elegantly dressed Black men run onstage to join them, one in a velvet double-breasted jacket, one in simpler garb. Their height dwarfs the already tall dancers behind them, but their subtle swagger is the largest thing about them. They are Complexions’ co-creators and directors, Desmond Richardson and Dwight Rhoden. They founded the company together; the whole evening we just saw sprang from Rhoden’s creative forehead.

Dwight Rhoden & Desmond Richardson

The double bill I just saw consists of two blocks of dance, separated by an intermission, both choreographed by Rhoden: Woke (2019), and Love Rocks (2020). In Woke, twelve of the company dancers fiercely tilt, strike, and swing each other through the air in what the program calls “a physical reaction to the daily news.” It’s set to a sundry score swiveling between Motown (The Temptations), hip hop (Kendrick Lamar, Drake), lyrical R&B/Pop (Sam Smith), rock (Moses Sumney), and moving spoken word.

The piece begins with Kobe Atwood Courtney shaking his afro, pulsing up and down, and before we know it, we’re watching all twelve dancers emerge from curtains of colorful fog, illumined by columns of bright changing lights. They turn, kick, strut. It’s a stunning spectacle. The dancers are titans; each looks hand-picked to form an elite warrior class. The staid concert hall is transformed into a rave, strobes accentuate the tension and velocity of solos into trios into duets into group numbers. I’m reminded of a concert, maybe David Bowie, in the presence of pixie-haired gank queen Jillian Davis.

As the initial bracing impression – of seeing these models flex their muscles, tilt their legs over their heads, and punch at the air – fades, one realizes that the choreography is actually quite frontal and straightforwardly structured. The movements are done on the beats, not ever off or in counterpoint; Kick on the one, turn on the two, arms out on the three, body roll on the four, and so on. The style is unmistakably commercial – So You Think You Can Dance meets Mad Hot Ballroom with heels & pointe shoes. Any one of them could be backing for music videos, and probably are on the side. When melodies play, the movements (initially so exciting) start to blend together. If everything is yelling, nothing is. And then the spoken word plays.

The poetry is by SULI Breaks, the stage name of English spoken word poet Darryll Suliaman Amoako. “To the victims of the gun crime and the knife crime: to them I say R.I.P.,” it begins, and then goes on to recontextualize that common acronym. It goes from “Rest in Peace” to “Read It Properly,” “Reside in Poverty,” “Rights in Property,” “Rob Innocent People,” “Rep it Properly” “Rifles in pockets,” to “Rewind it please, so we can remain in Peace.” One of the dancers languorously développés to the words, pulling out every syllable. At the moment his legs reach 185 degrees in the side oversplit, his head whips around in a flawlessly controlled motion that somehow echoes a gun being cocked, a bullet being released. This section is the most complex and avant-garde the piece gets – the most it resists easy cliché. And it’s a meaningful reaction to racialized police brutality, poverty, and gun violence. The audience gets goosepimples, a shiver down the spine, though the audio might achieve that powerful an effect alone.

Rhoden seems to like repetitive agitated movements, especially during moments of relative calm musically. At one point, all the women onstage end a sequence of music with rapid échappés, separating the legs and bringing them together manically, as the music fades out. Lines of men alternate with lines of women in front. I notice individuals: rapid chaînés of Tatiana Melendez, who is a joy to watch, the sensitive sheath of Marissa Mattingly’s flexing and softening muscles. If there’s one female dancer who represents the versatility and sheer flexible brilliance of this company, it’s Christian Burse, who dazzles consistently in Forsythian pointework.

But the overall impression is that the dancers are overworked by the simplistic and repetitive choreography, unchallenged by it to ever resist or surpass the music. At one point, two men dance a same-sex romantic duet to a song whose refrain repeats “I found you.” The performativity and drama are palpable, the connection between them, not so much. Subtlety doesn’t seem to be in Rhoden’s vocabulary. At the end the dancers kiss on the lips, a beautiful, fleeting moment, but even then they seem never to really connect, to share that kiss. It may just be me, but I am not interested, especially during Pride month, in seeing projections of who we as queer men want to be, superman muscles to hide our gooey insides. I want to see something unvarnished.

There’s nothing messy, nothing real, about the intimacy of any of the duets. Even when the women on pointe being partnered, as Christian Burse and April Watson often are, kick and turn and tilt strongly, forcefully, or when the men rant and rave and shake themselves and jump up and down in place, the emotions never feel human or intimate. They pretend hurt, pretend love, pretend anger. Choreographically, Rhoden is limited by the one color in his palette, which is the dancers’ athleticism and raw physicality. The choreography doesn’t help the talented dancers achieve any kind of emotional transference, because it forces them into a rigid and basic commercial formula. The dance made me see nothing else except for the dancers’ talent, their effort and work, the intention of the choreographer to impress. It felt like the kind of choreography of a person who has a lot to say, but has never challenged his own habits, has never questioned his ability to simply ejaculate it into movement.

Complexions features a racially diverse cast of dancers – at least seven of the eighteen listed in the program are visibly of color – and that in itself is a marvel in the extremely segregated (still) world of ballet. And the diversity of the dancers brings a more diverse audience than the usual one for ballet, which is a salutary change. That said (it’s not PC to say this, but have a duty to), I wonder how much the barriers to access for Black dancemakers create a smokescreen which shields Dwight Rhoden from scrutiny. From his choreography I constructed a vision of him as charismatic, and as with many charismatic creators, certain gradations of quality are overlooked. To criticize a work called Woke is a serious transgression, but if being in the dance world taught me anything, it’s that charismatic egotists often hide behind altruistic messages and personal connections to the work.

Love Rocks (2020), had the same choreographic imprimatur of Rhoden’s – high kicks, a female dancer running into a male partner’s arms to be spun through the air vertiginously, pirouettes and tilts. It was choreography meant to impress, but with a lighter subject matter: rock & roll and having fun. Set to a score completely comprised of Lenny Kravitz songs, it was a rollicking rock ode to being young and sexy and queer and freaky. And the dancers smiled!

I couldn’t take my eyes off of Thomas Dilley the whole time, who seems at the height of his powers. His physical control, flexibility, and speed were only surpassed by the brightness of his smile and the way it shone through his body. It is so rare now to encounter dance that is truly authentically joyful – and it was special to see. I am the last person to advocate that dance should express only easy, happy things; dance should absolutely be used to express anger and frustration and minoritarian struggle. But in this case, Rhoden’s melodrama felt more apt to this second piece, and authentic joy felt more powerful than either inauthentic drama or authentic rage that was stifled in by the very choreography meant to showcase it.

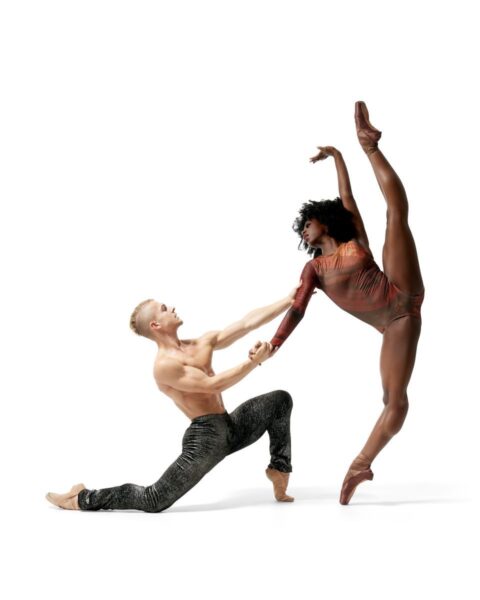

Jasmine Heart Cruz & Kobe Atwood Courtney

Dancers Candy Tong and Jasmine Heart Cruz mesmerize in Love Rocks, their power and joy exploding through arabesques and jumps and promenades and turns. At one point two dancers were lifted and brought together, their pointe shoes touching in a Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel moment. I enjoyed the piece, my mind wandered. And when Vincenzo di Primo stepped forward afterward to take a separate bow as the soloist, my companion and I were both surprised. Di Primo did a very cool pirouette, ending on balance, in the men’s dance, but we still weren’t quite sure he was intended to stand out from the crowd. Which gets at an unfortunate limitation of Rhoden’s prowess that bled into this piece: you don’t know where to look.

My takeaway from the evening was one of curiosity about Rhoden’s psychology, so as to avoid too direct condemnation of the ways the dance fell short. I tried to distract myself with the positive elements (the diversity, production value, talent of the dancers!) so as to not fixate on the squandering of a rare opportunity to be serious, to use dance to convey anger, which it almost never successfully does in ballet. The show reflected a middle place in our collective journey toward a more just society – the world of political almost art, dance that “tries to say” instead of saying. Dance that says more about the psychology of its creator than about the world. Dance that doesn’t take on a life of its own.

After the performance my dance companion and I walked outside, surveying the outfits of the theatergoers exiting the Music Center. A little girl ran in front of her mother. She began kicking and turning, lifting her leg in arabesque. I put my notebook down; maybe it’s enough that a performance inspires you to move joyfully. So my recommendations are thus:

See Complexions (but not the Double Bill) if you are ever in New York. Make sure they’re doing a mixed bill. Rhoden’s choreography is good once, but if you’ve seen five minutes you’ve seen it all.

See Complexions’ Double Bill with your kids. (If you want them to feel as free as the dancers smiling onstage in Love Rocks.)

Don’t See Complexions’ Double Bill if you want to see the potential of dance to convey real emotions – if you want to see things other than muscles flexing onstage and egos flexing off.

publicity shots by Rachel Neville courtesy of The Music Center

Complexions Contemporary Ballet

Love Rocks & Woke

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 North Grand Ave

played June 16-18, 2023

for more productions, visit Dance at The Music Center

for more info, visit Complexions